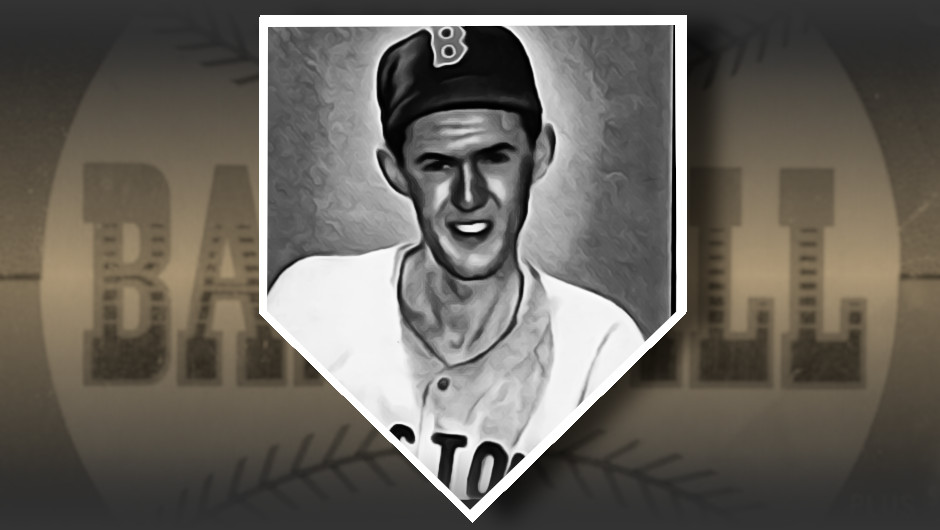

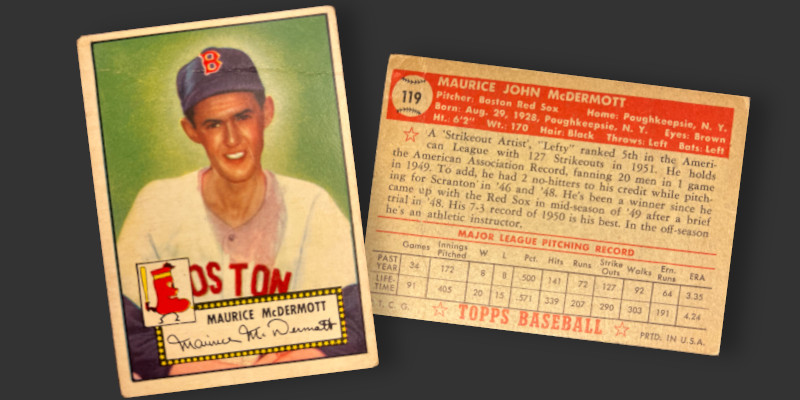

Needing just three more names to complete the second series of the 1952 Topps checklist, I clicked the “add to cart” button on the first one I came across on COMC. The resulting purchase has the typical corner wear and centering associated with examples from the set, alongside a fairly substantial crease running through the top of the image. All things considered, this was not an acquisition I am particularly proud of. Six bucks for a creased Mickey McDermott? That’s a bit much.

My internal beef with the card isn’t entirely the result of rushing to overlook that crease — the card features an overall weird looking image of the pitcher from Poughkeepsie. The way he is posed with arms resting on his lap implies the picture was taken while seated. Given the missing backdrop and slight lean to his posture, I suspect the original image may have been taken as part of a team photo. The cropping isn’t doing much to make his 6’2″, 170-lb. frame look any more substantial. I look at the card and worry he’s not getting enough food on the road.

Topps’ placement of the term “Strikeout Artist” in quotes made me immediately double check to see if he was indeed a pitcher and that this was not a back-handed compliment for some underweight middle infielder. ***Checks Notes***…Yep, Mickey was a pitcher and a pretty adept one when it came to inducing swings and misses.

His status as a strikeout artist and southpaw delivery contributed to the next use of quotes — “Lefty.” As a teen he authored more than just a few minor league no-hitters. A pair of 1-hitters in 1953 coupled with nearly 20 wins proved this wasn’t a fluke. A fastball said to hit triple digits prompted Birdie Tebbetts to pronounce the phenom as being well on his way to becoming the next Lefty Grove. In the end, McDermott’s resemblance to Hall of Fame pitching talent was less Lefty Grove and more akin to Pete Alexander.

To say McDermott had an impressive arm was an understatement. His SABR bio recounts the time he struck out 27 batters in a 7-inning high school game. He impressed the Brooklyn Dodgers enough at an open tryout to generate a recommendation to sign the youngster, but the potential deal fell through when the club learned that he was only 13 years old. Two years later he repeated the contract-inducing performance in front of a Red Sox scout and successfully used a doctored birth certificate to pass muster with any concern over compliance with child labor restrictions.

The velocity of McDermott’s pitching arm quickly overrode any qualms over the ill-kept secret of his true age, as well as some of the other aspects of his renumeration. The Sox paid a $5,000 signing bonus as well as two truckloads of Ballantine Beer. Presumably this suds-laden convoy from Newark was split between the pitcher and a police-officer father who seemed to not be a completely “by the book” kind of guy.

The Red Sox ethos of the era matched up pretty well with McDermott’s partying ways. Team owner Tom Yawkey, after all, was heavily involved with the establishment of a brothel that operated for decades in South Carolina (read all about the history of the Sunset Lodge here) and had no problem rigging contracts in ways that hid money and reduced alimony payments on behalf of his players (I’m looking at you, Ted Williams). One of McDermott’s first big league assignments in 1948 was to take over a game started by Ellis Kinder, who was yanked for being too drunk to continue pitching. By the end of the season the teenager was moonlighting as a lounge singer in exchange for $500 a week and all he could drink.

You can guess (most of) the rest of the story. Curfew had no meaning and the drinking became constant. McDermott’s off-field wildness crept further and further into his on-field performance. Still armed with an explosive fastball and keeping batters close to the Mendoza line, McDermott saw his WHIP run above 1.50 as he racked up bases on balls left and right. Tiring of his late nights and too-brightly lit mornings, his career as a Red Sox starter morphed into a rotating tour of the bullpens of other American League cities. He caught on with the Yankees for 87 innings in 1956, enough to get the World Series ring that would accompany him to bars for the rest of his life.

After baseball he went through the predictable series of disjointed jobs. The police offer’s son became a security guard. When that didn’t stick he became a carpenter. An attempt to turn his passion for the nightlife into a second career resulted in drinking his bar into insolvency. A night of drinking with a local dentist may have even resulted in an impromptu replacement of his teeth. By the early 1990s Ted Williams had put him on his payroll of down and out teammates in need of cash.

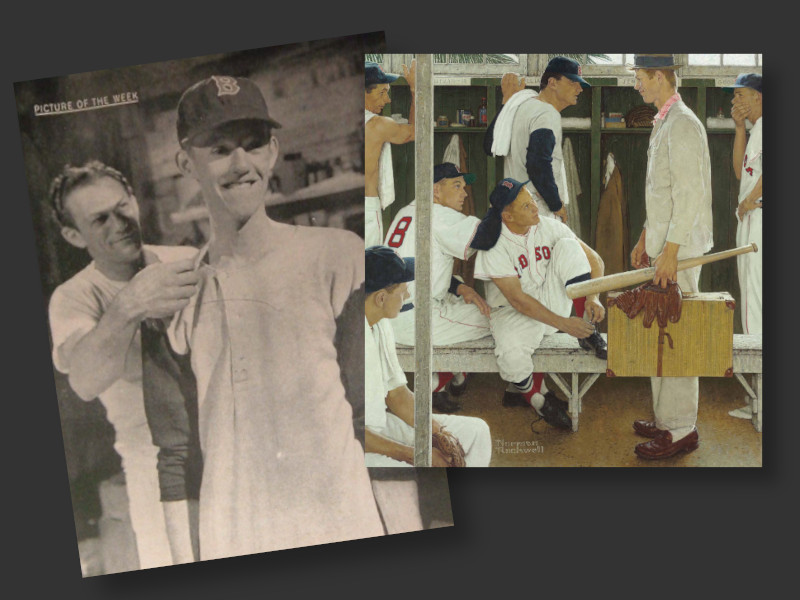

From what I have read, I get the feeling that the former Red Sox/Senators/Yankees/Athletics/Tigers/Cardinals pitcher would have been more than willing to chat up fellow bar patrons about glory days on the mound that had long since passed. He may have regaled them with the history of his Yankees ring, though that only came about in a single appearance as one of 6 pinstriped pitchers used in a 13-8 loss to the Dodgers. His go-to story seems to have been a claim to be the inspiration for a Norman Rockwell painting that was completed the following year.

McDermott’s claim to the artwork (above right) stems from the Life Picture of the Week shown on the left. It features the grinning pitcher receiving treatment for a sunburned neck after his first day of Spring Training. The accompanying caption titles the image as “The Baseball Rookie” and talks of the unbounded optimism required of a newcomer experiencing the trials of his first day in camp. McDermott, who was not a fan of the photograph, would go on to claim that it made him the living embodiment of the apocryphal “baseball rookie” in all its forms.

Painted nine years later, Rockwell’s image portrays a fictitious rookie walking obliviously into Boston’s Payne Park locker room in Sarasota. “Greeting” the rookie are an incredulous Ted Williams, Sammy White, Frank Sullivan, Jackie Jensen, and Billy Goodman, as well as a shirtless and aptly-named “John J. Anonymous” at the far left. The uncoordinated teenager at the center of it all was a 17-year-old pulled from the lunch line of a Vermont high school.

Rockwell never claimed the rookie was intended to represent McDermott. He reached out to multiple Red Sox players to model for the painting and specifically asked for Williams’ permission before putting him in the image. Jensen, tying his shoe on the bench, actually came to the Boston lineup from the Senators in a December 1953 exchange for McDermott. McDermott seems to have about the same claim to being “the rookie” as any of the other 10,942 other players that came before Rockwell’s 1957 canvas was dry.

McDermott, it seems, was ever the optimist. He put out the memoir A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Hall of Fame in 2003 and was adamant that he is the inspiration for the gangly teen in the ill-fitted suit. A series of McDermott-autographed prints of the painting can still be seen in Florida drinking haunts. That optimism was perhaps never more on display than when in 1991 he purchased a $1 lottery ticket, drank himself into a stupor, and woke up with a net worth somewhere close to $7 million.

McDermott’s story is one I would have expected to end with a failed liver transplant. Instead, he appears to have turned things around and gone sober following the lottery drawing.

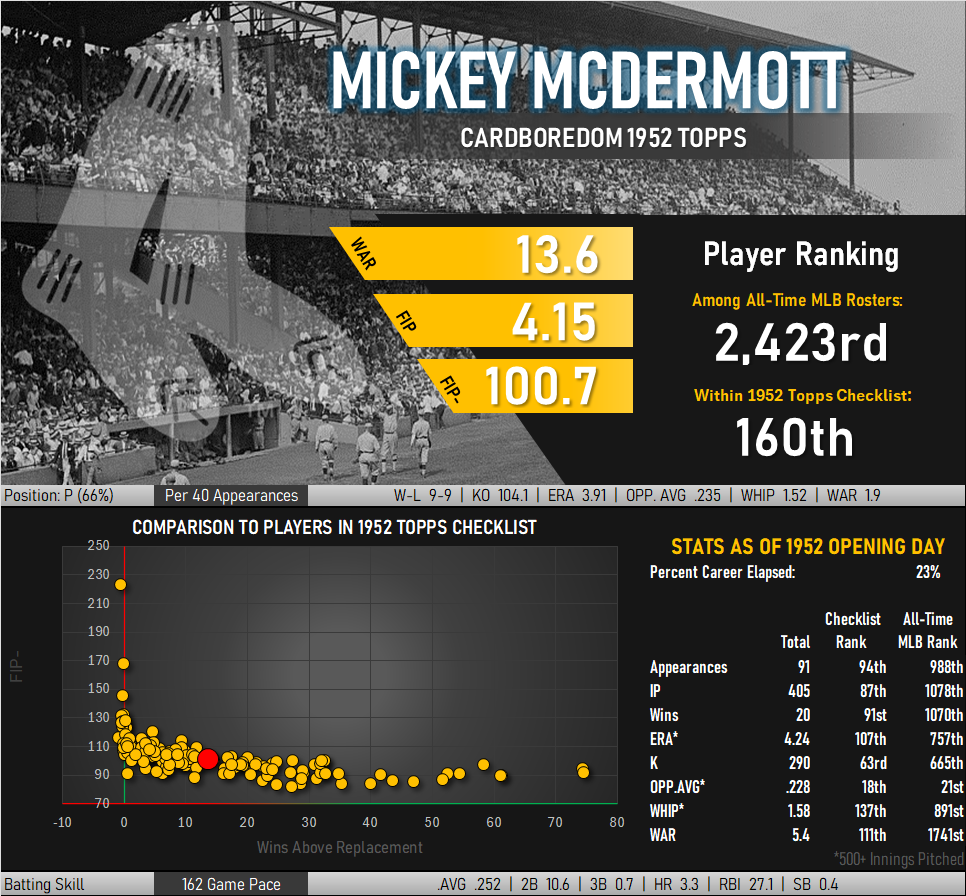

While a funny thing may have happened on the way to Cooperstown, a funny thing also happened in the compilation of McDermott’s statistical tables. He was a pitcher that held opposing batters to a .235 batting average, a figure well within the top-100 performances of MLB history at the time of his retirement and better than that of Christy Mathewson and Warren Spahn. For his part, Spahn named McDermott (alongside Ted Williams) as the best athlete he had ever personally witnessed play the game.

Why invoke the name of “the greatest hitter who ever lived” alongside McDermott? Perhaps because this pitcher outhit the collective effort of every batter he ever faced by 17 points. His career batting average of .252 contributed to one third of his MLB appearances coming in the form of pinch hitting assignments rather than pitching.