Gil Hodges, a key component of contending Brooklyn Dodger teams and later a successful manager of the champion 1969 Mets, will be inducted into the Hall of Fame this year. Another New York icon will not, though he did have a similar background and career arc. The closeness of their stories is compelling with Hank Bauer seemingly getting the worst side of it in most instances.

Both grew up in tight financial conditions. Hodge’s father was a partially blind coal miner who worked through the loss of his toes to feed the family. Bauer’s father lost a leg and tried to make ends meet as a bartender. Funds were tight in the Bauer household, sometimes forcing Hank to wear homespun burlap clothing.

Both had a brief shot at baseball before going into the Marines for WW2, both attained the rank of sergeant, and both saw extensive fighting in the Pacific Theater. Stories of military toughness followed both, with Hodges said to have killed enemy soldiers in hand-to-hand combat and Bauer becoming one of only 6 of 64 in his unit to survive a particularly fierce encounter.

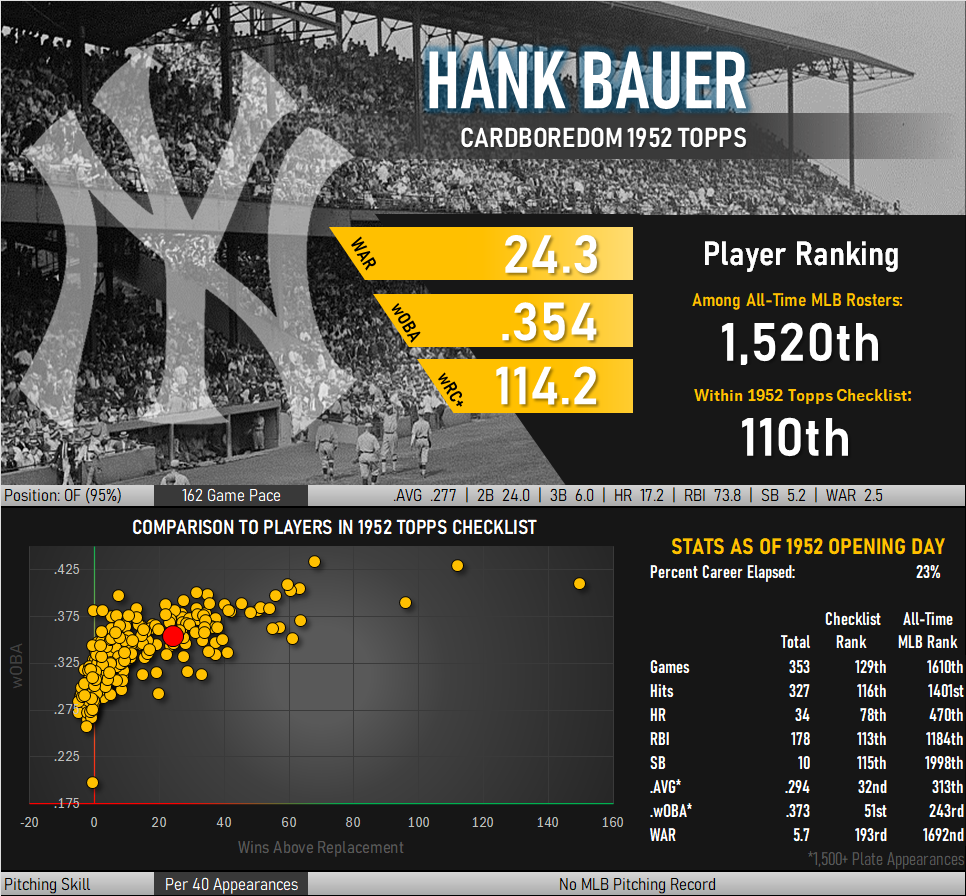

Hodges and Bauer each put up career statistics that place them among the better players of the era. Neither had the on-field stats alone to warrant inclusion in the Hall of Fame, but both were consistently productive members of rival teams that competed annually for more than a decade for championships. Hodges generated the more substantial regular season resume but Bauer shone in the World Series, setting a record with a 17-game hitting streak and winning decisive games with clutch hits. Hodges had the edge as an everyday player, but Bauer performed best when everyone was watching.

Both New Yorkers found themselves added to the roster of obscure teams at the end of their careers. Hodges was sent to the Mets in the 1962 expansion draft while Bauer was traded to the Athletics for Roger Maris in 1959. Both men would go on to obtain the role of manager for these clubs. Hodges turned the last place Mets into a surprise World Series champion in 1969. Bauer had turned around the 1960s Orioles that faced off against Hodges in that series, though he had been replaced in Baltimore by Earl Weaver the year before.

Meeting Bauer (or at Least His Shoes)

When I was a kid in the mid-1990s, my dad packed me into the family car and drove to the Coast Guard station in Yorktown, Virginia. He told me Hank Bauer would be signing autographs at the station’s baseball card show and I wanted to meet one of the famous 1950s Yankees. We paid our admission and I handed over $5 or $10 for a ticket allowing me to have one item signed. A 1994 Archives reprint of Bauer’s 1954 Topps card in hand, I went in search of the autograph line. I made a circuit of the show floor, and not finding the line, decided to ask for directions. I approached a table at which two older men were seated and asked where I could find Mr. Bauer. The one on the left smiled and jerked his thumb towards his seatmate.

The other man leaned forward and growled, “I’m Bauer.” I looked at the ground and remember seeing his shoes under the table. They were among the shiniest dress shoes I had ever seen. In fact, the only other times I saw shoes like that they were being worn by WW2 and Korean era Marine Corps vets. After scaring me for thirty seconds he smiled and signed my card. Today I cannot recall his face from this encounter, but I clearly remember those shoes. After signing we exchanged a “thank you” and a reciprocal “you’re welcome.”

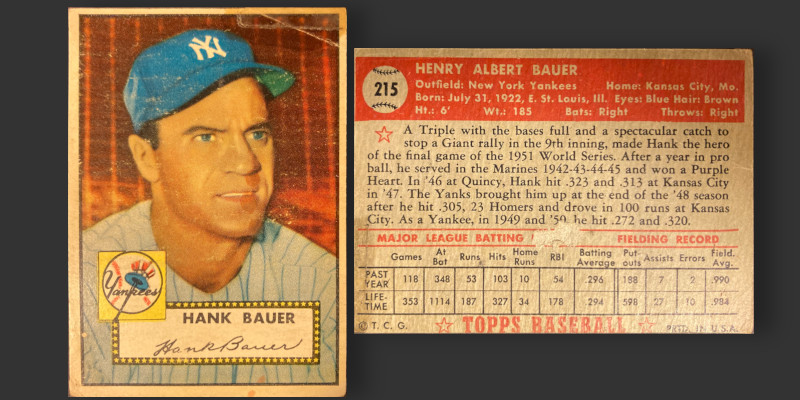

1952 Topps Hank Bauer

I no longer have my signed Bauer card, having included it when I sold my original collection to pay for school 20 years ago. Today the sole Bauer card in my collection is this example from the 1952 Topps set. The card was purchased on eBay and has been trimmed on all sides. The seller omitted this from the description, stating only that the card was in “low-grade.” Hank probably would have punched him out.