There is a collective inhalation whenever a thrown baseball strikes a batter. Everyone in attendance knows the sting inflicted from a pitch thrown at 40-50 miles per hour, the kind of velocity found on school game or sandlot. Everyone also knows that the same ball traveling through the air of a major league ballpark will be coming at nearly twice that speed and hitting with much more intensity.

What follows that sharp inhalation is one of three sounds. If the ball is thrown by a visiting pitcher there will be a cacophony of jeers. If thrown by the home team the air is frequently filled with the angry murmur of fans sorting out if they are happy or not about the violence they have just witnessed. The final sound is one of shocked silence. Like the crack of a bat on a well-hit ball, there is a distinctive sound made when a ball hits someone’s head. The batter falls straight to the ground as this unique sound reverberates across the stadium. You know from the sound alone when someone is badly hurt. Every couple decades there comes a pitch that stands out as a defining bean-ball of a generation. Decades later those that were in attendance can still recall what their ears heard.

The most famous of these came in a 1920 contest between the visiting New York Yankees and Cleveland Indians. Yankees hurler Carl Mays was facing Ray Chapman, a speedy infielder that had bunted in both of his previous trips to the plate. Mays sent a ball high and inside, striking Chapman in the head and leading to him collapse as he turned to take his base. Chapman’s skull was fractured and he died from his injuries the following morning.

17 Year later there was another life-threatening silence on a ballfield. Detroit Tigers player/manager Mickey Cochrane was 1 for 2 with credit for a solo home run that tied the game in the third inning. Bump Hadley of the New York Yankees began his third faceoff of the day against Cochrane with a fastball aimed right at his head. Unlike Chapman, Cochrane didn’t even get to look in the direction of first base before going down. Hospitalized with his skull fractured in three places, Cochrane spent the next week and a half in a coma. He never played again.

Exceptionally vicious beanings apparently have the timing of cicadas. After the passing of another 17-year interval there came another head-hunting fastball that defined the pitch for a generation.

The Chicago White Sox were finally beginning to put together some winning seasons that would culminate with winning the American League pennant five years later. Speed, hitting for contact, and great defense were the cornerstones of these White Sox teams. Players such as Nellie Fox and Minnie Minoso (both traded away by various levels of the Philadelphia Athletics organization) epitomized this approach.

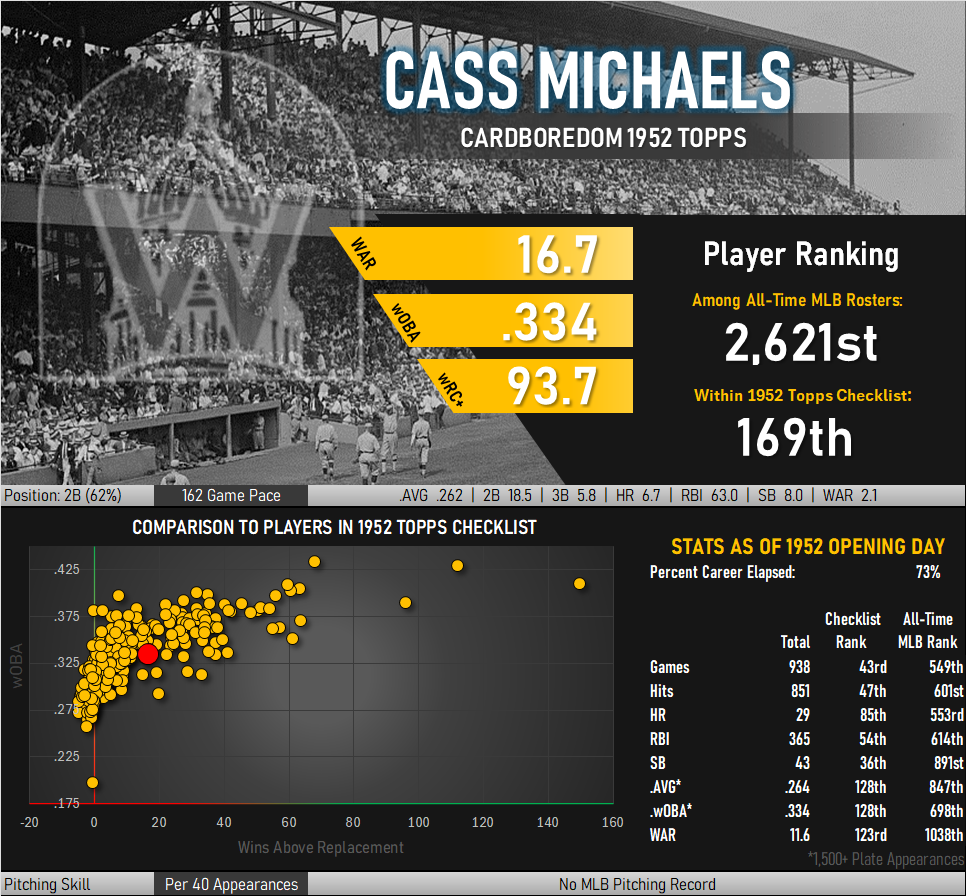

Another player in this mold was Cass Michaels. Michaels had been plucked from sandlot ball in the early 1940s, becoming one of the youngest professional players in the game’s history and earning him the nickname “Boy Wonder.” The name Michaels itself was something of a nickname, as he repeatedly shortened and renamed his surname (Kwietniewski) to allow it to better fit in the limited space afforded to newspaper box scores. Michaels struggled a bit at first but had come into his own as the 1950s dawned, earning a pair of All-Star selections for the American League.

In this particular game of August 27, 1954, Chicago had blown open the score against the hometown Philadelphia Athletics. The White Sox scored five runs in the third inning off starter Marion Fricano. Michaels, himself a teammate of Fricano’s the previous season, came to the plate and was immediately hit with the first pitch thrown by the agitated pitcher. Initial news reports state that Michaels was bleeding from his ears and taken to the hospital. The front page of the next morning’s Chicago Tribune speculated his skull may be broken and credited “the protective armor in his cap” with blunting the impact of the pitch. He fell into a brief coma shortly thereafter, awakening with vision problems that would continue to follow him. Michaels missed the remainder of the season. He tried to return the following year, but retired after losing consciousness on the field just two days into 1955’s Spring Training.

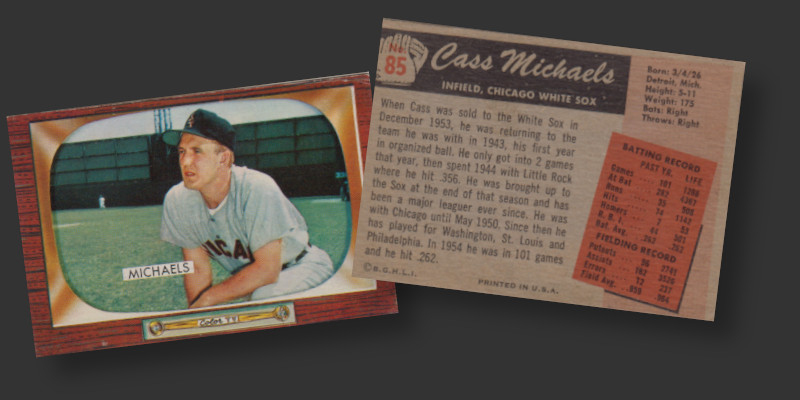

Michaels’ career ended prematurely in 1954. Bowman thought he would soon return to the Chicago lineup and included him as card #85 in the gum manufacturer’s 1955 baseball set. The text on the back makes no mention of his having been hit by a pitch.

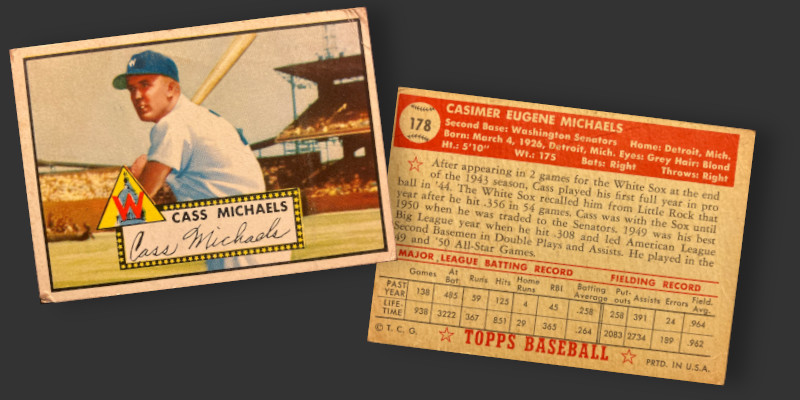

A ’52 Topps Cass Michaels Card Joins the Collection

Michaels saw a lot of American League ballparks in 1952, and we get a good look at Comiskey Park in the background of his 1952 Topps card. The stadium’s unique centerfield seating and the pair of upper deck exit ramps visible further back make the setting fairly easy to identify. Less identifiable is the action taking place in centerfield itself. It looks like the grounds crew is rolling up something, though it also kind of looks like a group of explorers is paddling around in a canoe. Upon magnification of the image I see it is five men pushing a tarp rather than the expedition of Lewis & Clark. You can even make out the outline of Comiskey’s giant clock adorning the outfield wall.

Michaels played most of his career for Chicago and even played more than a third of his games in Comiskey Park as part of either the home or visiting squads. Michaels had been traded to the Washington Senators in 1950, an event discussed in the biographical text on the back of the card. Not mentioned, however, is the fact that Michaels was already on the move again when this card was made. In May of that year he was traded to the St. Louis Browns for Fred Marsh and Lou Sleater, both of whom made appearances on that year’s Topps baseball cards. Sleater’s card was released later in the season, allowing Topps to depict him as a member of the Senators. Marsh, who was to become the pinch runner standing in for Michaels after his 1954 beaning, is shown playing for St. Louis.

Had Michaels’ card been released in the late-season high numbered series he may have worn another uniform altogether. In August the Browns made him available to other teams on the waiver wire. The Athletics picked up his contract and he finished the season in Philadelphia. Looking back at the season, he actually appeared in an equal number of A’s and Browns games while getting into just 22 contests as a Senator.