When Michael Lewis first set out to write the book that would become Moneyball, he was not seeking a story about the finding an efficient way to allocate the payroll of a Major League Baseball team. What he initially sought to uncover was the way in which professional athletes viewed teammates making wildly disparate incomes that often did not align with their onfield results in a linear fashion. While the Oakland Athletics ultimately generated a different storyline for Lewis to follow, it was the Boston Braves of the late 1940s that provided insight to compensation dynamics.

The Braves of this era were a fairly dangerous team led by several highly capable starting pitchers. The two best known hurlers were Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain, a pair immortalized in the game’s literary history through a poem advising the team’s pitching starts to follow the pattern of “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain.” Both were very good and knew it. Neither was pleased when Boston signed Johnny Antonelli, a teenager, to replace the rain clouds in the starting rotation.

It wasn’t the addition of a highly capable arm on the staff that tweaked these pitchers, but rather the fact that the Braves paid a previously unheard-of signing bonus of $52,000 to get him on the team. In keeping with the MLB rules of the time, any team paying a signing bonus had to assign the signed player to an active roster spot for an extended period with the Major League team. There was no minor league seasoning available. This meant teams using bonus structures to sign new players would have to either throw their new recruits up against entrenched MLB talent right away or eat up valuable roster space sitting on the bench for much of the season.

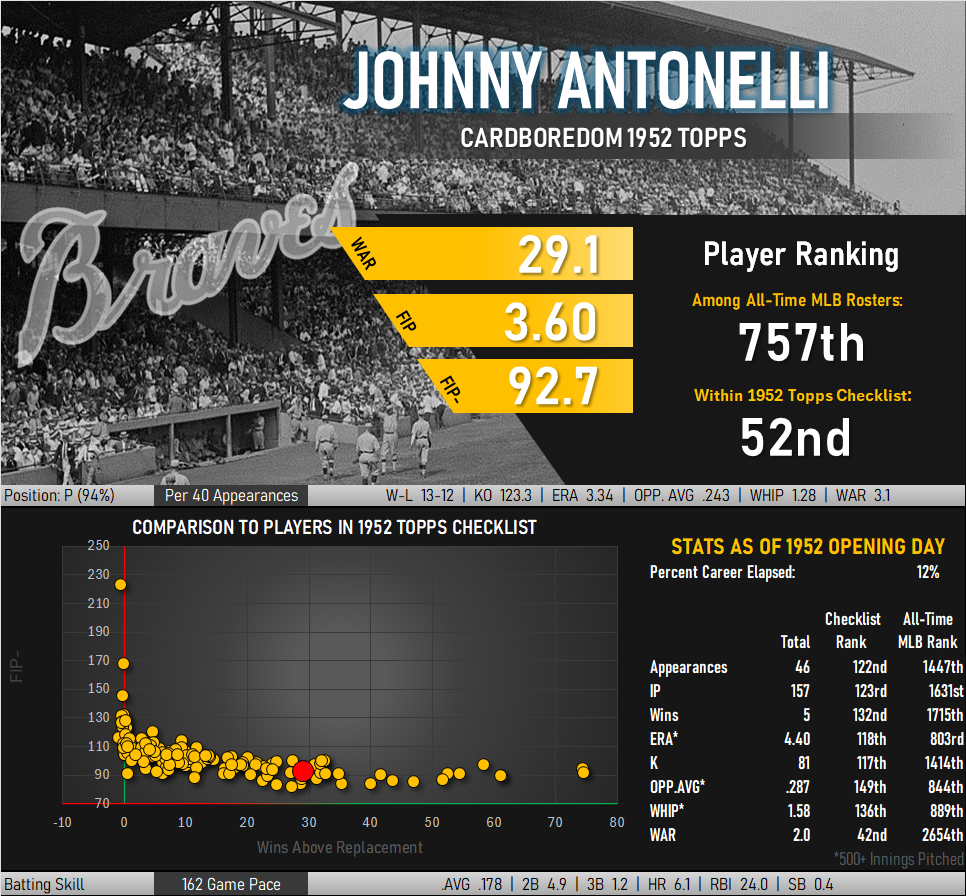

Antonelli’s early seasons followed this pattern with the 18-year-old only seeing four innings of action in his debut season. He recorded 96 innings in his second year with the club and a few dozen more in his third. He generated a 5-10 record during this span with a 4.40 ERA. Warren Spahn, meanwhile, pitched in almost 900 innings, 66 complete games, a 3.29 ERA and a record of 57-43. Johnny Sain logged 836 innings on his way to a 3.69 ERA and 54-49 record. Their records made it abundantly clear who the more effective and most worked arms were in the Braves’ organization.

Antonelli’s signing bonus was absolutely massive compared to what the longer-tenured Braves pitchers were earning. Spahn was taking home $32,000 at the time and Sain was barely topping $20,000. The latter erupted at Boston’s front office over the newcomer’s contract, prompting a seldom-seen midseason salary renegotiation to $30,000 as he threatened to quit the team. Spahn reportedly wouldn’t speak to Antonelli when he first came to Boston and was continually vocal with his opinion that Antonelli was not worth the contract he had signed. Antonelli’s teammates froze him out of his share of 1948 World Series money, prompting the commissioner of baseball to step in and force the team to provide him with 1/8th of share.

So much for wondering what teammates think about salary differences.

Getting a Full Share of World Series Money

The diplomatic limbo in which Antonelli and his teammates found themselves paused in 1951. Just 20 years old, he was drafted into the US Army as the Korean War expanded. He missed the entire ’51 and ’52 seasons with military service, returning for a very effective 1953 season. His teammate, Chet Nichols, likewise missed several seasons with military service and was scheduled to return in 1954. With Antonelli’s contract continuing to be a point of contention among the team’s pitchers, his spot in the rotation was given to Nichols and he was traded to the New York Giants.

Antonelli then went on a tear. He won 21 games, spun an ERA of 2.30, and authored a half dozen shutouts that included blanking Warren Spahn in a 4-0 victory. The Giants surged ahead in the standings, ultimately winning the Worlds Series in his first year with the team.

His subsequent pitching stats show a remarkable career. He averaged 1.5 wins above replacement per 100 innings pitched, a level consistent with the performance of Baves Hall of Famers Phil Niekro and Tom Glavine. Fielding independent pitching metrics (FIP- of 93) show a dominant starter with good command, beating Warren Spahn (94) and Johnny Sain (97). On a per game basis, he very well may have been better than his miffed teammates.

This was all done in a short career that ended at age 31 with two years lost to the army and very limited playing time in his first few seasons.

Fun fact: Antonelli chose to retire from baseball rather than play for the New York Mets in 1962.

Bonuses and Retirement Planning

Talk of Antonelli’s contract makes him a flashpoint for discussions about what is considered fair compensation in the sports world. In this regard he reminds me of someone who encountered similar resentment across the NBA.

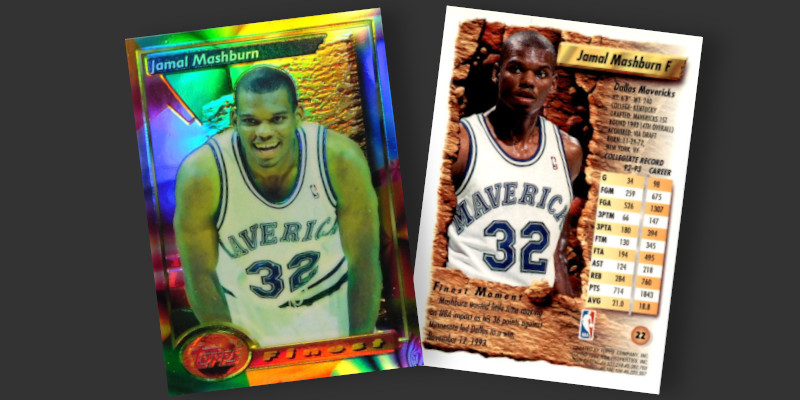

In 1993 the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks signed Jamal Mashburn, a college junior, to huge $32 million contract. On an annual basis the deal provided more money than even Michael Jordan was making at the time. Could such a young player be worth it? The seemingly out of proportion compensation drew widespread criticism. Dallas has lost their minds. There’s no way he’s good enough. He’s just going to blow it.

Mashburn would go on to play a dozen years in the NBA, generating substantial offensive stats that seem limited only by the gradual degradation of his knees. Including that sizable initial contract, he earned $75 million over the course of his career. That’s nothing to sneeze at, but numbers like this don’t mean anything if a player can’t hang on to it. Given resentment over large contracts and the ever popular 2009 Sports Illustrated story that reported the majority of NBA players are broke within 5 years of leaving the game, it would seem more than just a few people would be rooting for Mashburn to become one of the biggest names to financially crash and burn. Antonelli could probably relate.

Here’s where it gets really interesting. Mashburn didn’t go broke. He invested his earnings wisely, building a diversified portfolio of restaurant franchises, car dealerships, and real estate. His $75 million (likely closer to $30 million after tax) has blossomed into something closer to nine figures. Given the track record of athletes receiving life altering money at an immature age, Mashburn’s story makes one want to stand back and perform a slow clap of approval.

Antonelli strikes me in a similar way. Finally receiving a full World Series share in 1954, he used the $8,750 he earned to open a Firestone tire franchise in his hometown. He grew the business, eventually expanding it to three locations a little over a decade later. He made smart hiring decisions, eventually placing much of the business strategy in the hands of a man who expanded Antonelli’s tire stores to 28 locations and a few truck service facilities. Antonelli cashed out of his business holdings in the mid-1990s. By that point, he had shown his on field performance to be worthy of earning the exorbitant bonus and his financial management skills as worthy of keeping it.

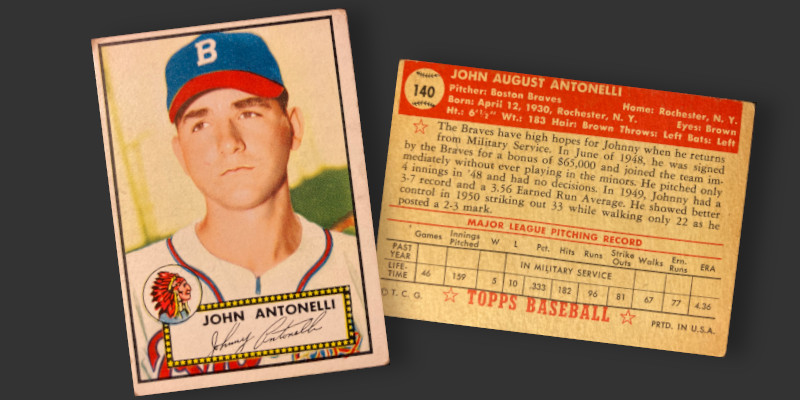

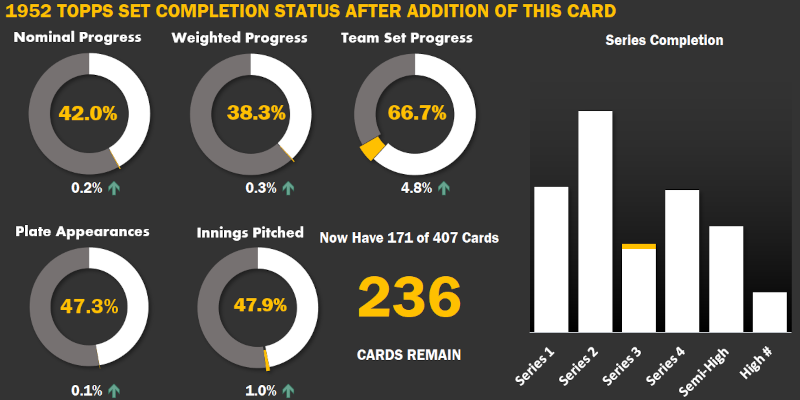

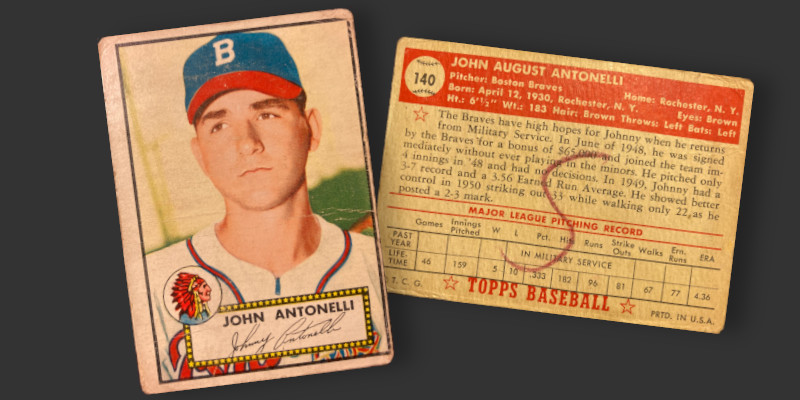

1952 Topps #140

As with the card of his teammate, Chet Nichols, Topps included Antonelli in the checklist despite him being actively involved in the Korean War. Both pitchers received cards with the simple stat line “In Military Service” written across the back. The addition of this card takes my 1952 Topps collection up to 171 cards and 42% completion. This wraps up my research into a run of eight commons I picked up from Dean’s Cards. For those who aren’t familiar with the name, Dean’s is an online card shop has specialized in vintage cards of all grades for 20 years. They have a reputation for carrying a wide selection of cards and being very knowledgeable about their wares. Owner Dean Hanley even wrote The Great Bubble Gum War, a small book about the Topps/Bowman rivalry of the early 1950s. I usually find the shop’s pricing to be higher than I would pay for most cards, but every now and then they post some really attractive offers (like on these 8 cards). I will keep browsing their selection as this set gets built, hoping for a deal.

Like many of my cards, this one saw active use from whomever pulled it from a pack. The corners are heavily rounded and a major crease runs across the middle of the card. Someone even marked up the back with a purple crayon (maybe they were drawing bonus baby dollar signs).

October 4, 2023 Edit: Well how about that? Just weeks after getting around to posting my Antonelli card I purchased a low grade commons lot in order to snag a couple 1952 Topps upgrades. A better ’52 Antonelli was mixed in with the group at a per card price about a third of what I paid for the first one. I’ll find a good home for the copy with the crayon “S” on the back.