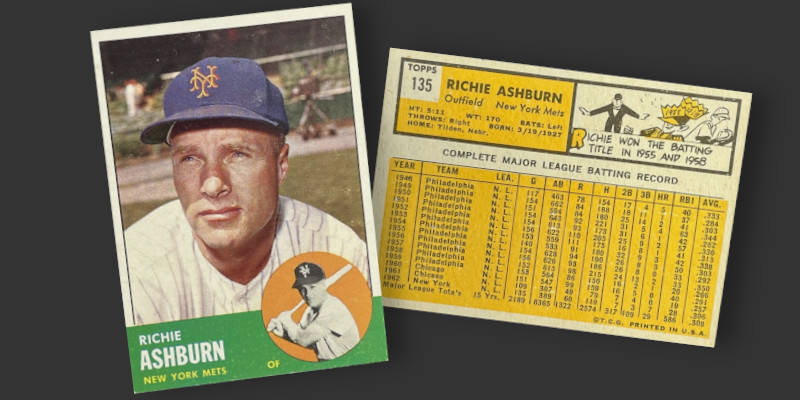

Here’s a fun baseball card from 1963. Card #135 from that year’s Topps issue features a New York Mets outfielder who had already stepped away from the game and into retirement. He’s clearly wearing a Mets cap in the primary image, but the black and white inset at the bottom right reveals a terrible artist rendering of the same hat. Viewers looking beyond the hats and into the background will notice a giant television broadcast camera over Richie Ashburn’s shoulder.

Turning to the back, one can find complete career stats and extract one of the more interesting facts appearing on a baseball card. No, not Ashburn’s multiple batting titles or his racking up more hits (1,875) than anyone else in the 1950s. It is, quite surprisingly for a guy with 29 career home runs, the fact that a huge chunk of those came in his final season. Ashburn’s seven home runs in 1962 more than doubled anything he had hit in the previous ten years and were greater than his cumulative total of the last six. That’s some good end-of-career power from a guy with lower home run totals than Deadball Era leadoff speedsters Wee Willie Keeler and Billy Hamilton.

Ashburn was one of the game’s quintessential leadoff hitters. His career on base percentage of .396 is just 5 points behind that of Rickey Henderson. He stole 234 bases, and while that number is dwarfed by Rickey, it was accomplished in an era in which the art of base thievery was practiced on a significantly smaller scale. His stolen base total is the third highest of anyone in his career’s 1948-1962 timespan. Ashburn got on base, routinely took the next one, and then scored (he’s also third in runs over that same period).

Topps had a lot to play with in those numbers on the back of his 1963 career capstone card, and selected his multiple batting titles as the fact most worthy of being called out in the comic in the upper right. Personally, I would have highlighted Ashburn hitting the same spectator twice with foul balls in an August 1957 plate appearance but can understand why Topps instead wanted to focus on what he did between the foul lines.

I first learned baseball stats in the in the early 1990s. Like a lot of kids of this and earlier eras who gleaned information from the back of baseball cards, I had a bit of an overdeveloped obsession with RBIs. That’s probably why I initially passed over numerous Ashburn cards when I was first getting into the vintage side of the hobby. Looking at the back of that ’63 Mets card, for example, I see his 1958 batting title resulted in driving in just 33 runs. He didn’t even get to 600 RBIs in his career, while 10 players eclipsed his total in my high school years alone. Ashburn wasn’t going to get my attention when “number go up” was the sole driving force of how I perceived the game.

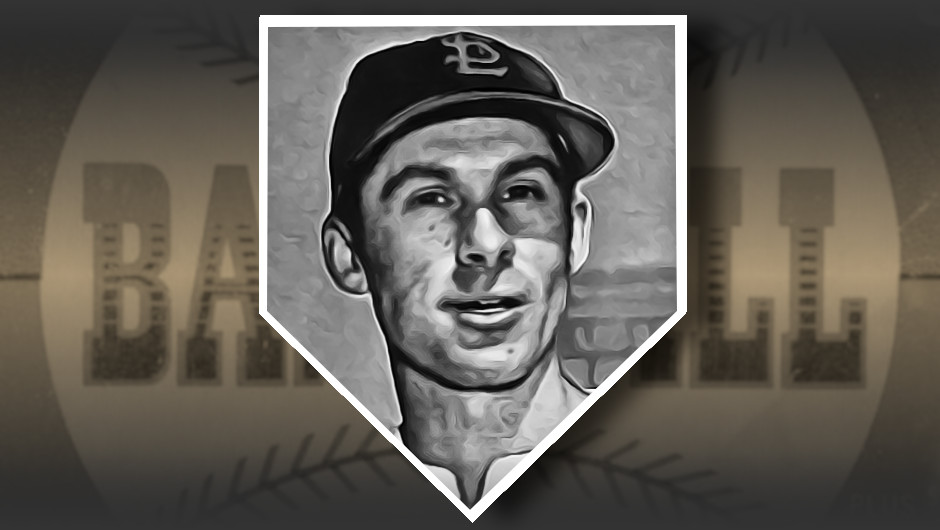

The fact that Ashburn hit the same number of career home runs as my favorite player launched solely in his rookie season probably didn’t help. Like Don Mueller on the ’52 Topps card I recently profiled, Ashburn was a singles hitter. Just how much of a singles hitter was the 1955/58 batting champ, you ask? One-baggers accounted for more than 82% of his hits, well above the 70% average seen across all batters in the first century of the Live Ball Era. Among the thousands of players to safely hit their way onto a base, he ranks in the 94th percentile in terms of that base knock being a single. Considering the fact that the vast majority of those above him are weak-hitting pitchers, Ashburn can safely be considered one of the game’s singular singles hitters.

These hitters rarely stand out in the record books. Sure, names like Sandy Alomar, Sr. and Otis Nixon get mentioned from time to time. Lloyd Waner even made the Hall of Fame and was recently joined by Ichiro, who was less likely than Ashburn to get a single.

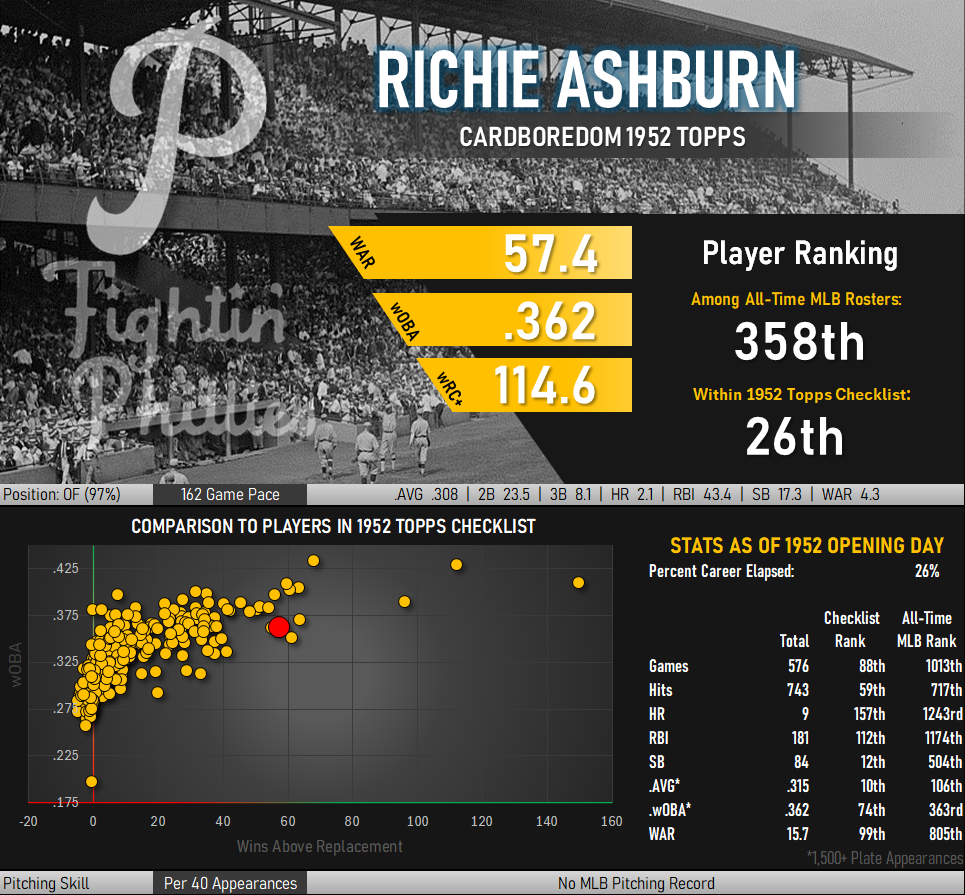

Why am I, a self-professed home run nut, so obsessed with counting the game’s least valuable hit? It is because my go-to stat for measuring player performance is weighted on base average (wOBA), which is essentially a batting average that incorporates the relative value of how a player gets on base. While singles are better than walks, wOBA is significantly affected by generating extra base hits. Guys like Luis Arreaz (wOBA .316) win batting titles with singles, but have a barely above average contribution to their team’s overall offense.

Here’s where my amazement with Ashburn comes in: He generated a lifetime .362 wOBA. That’s the same level as Johnny Bench and better than Roger Maris, Derek Jeter, and Dale Murphy. Among current guys this is better than Manny Machado and on par with Pete Alonzo. This came despite averaging two home runs per season and getting extra base hits at one of the lowest rates of anyone in the last century of baseball. It is absurdly hard to get the math to work out that way. Among players with such a high rate of hitting singles, he is the second highest ever in terms of wOBA, trailing only a Tigers catcher from the 1920s.

While not really reflected above, Ashburn was an incredible outfielder with lots of range. He ranks third in all time putouts from center field, trailing only Willie Mays and Tris Speaker. Considering that these legends each accumulated their totals over 22 seasons while Ashburn secured third place in just 15 really puts his production into perspective.

Some Cards Have More Trouble Than Others Getting Into My Collection

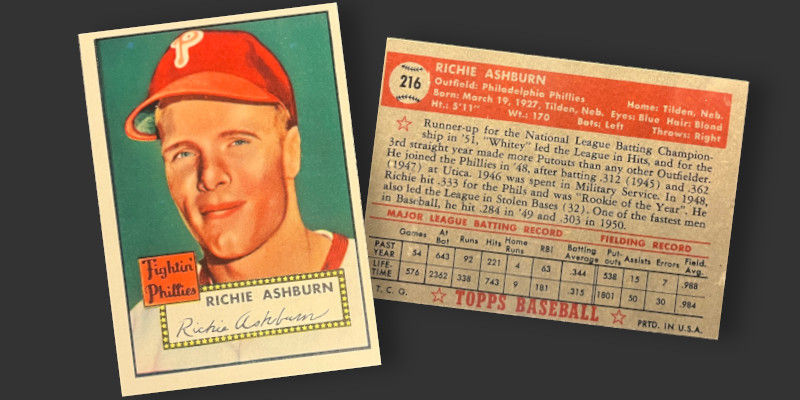

Richie Ashburn’s ’52 Topps card took its sweet time getting into my collection. Four years ago I purchased a trimmed example off eBay for $15. Here’s what showed up at my door instead:

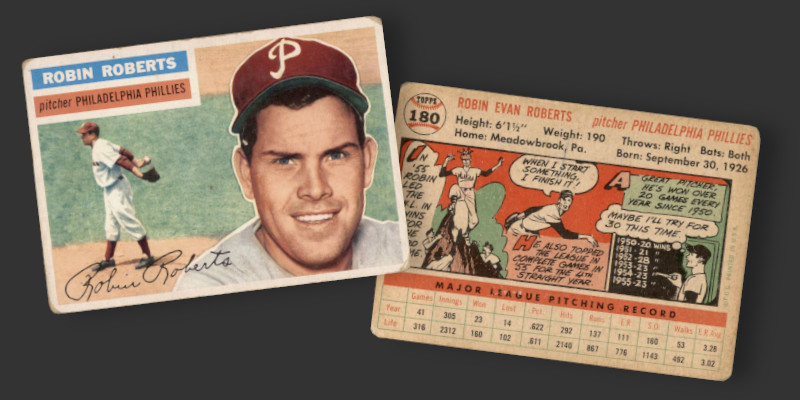

That’s a Robin Roberts card from 1956. The seller had two auctions ending at the same time and apparently switched up the outgoing envelopes. I returned the errant Roberts card and was refunded after the intended Roberts recipient kept my Ashburn and hit the seller for an “item not as described” refund. Gross. Someone sold their integrity for a $15 piece of cardboard.

I shrugged and moved on. As part of the heavily printed fourth series Ashburn’s 1952 Topps card isn’t hard to find. What was hard to find was one at a price matching its condition. In super high grade this card struggles to command more than $200 as it is, after all, just a mid-career card of Richie Ashburn. Any significant wear on it and it theoretically should be available well below half this amount. That’s where the pricing craziness of the past few years comes in. It took years for me to track down a copy at any sort of reasonable price.

I made multiple trips to the big Chantilly card show, the biggest in the Virginia and one that pops up three times per year. This card is easily found on multiple tables, but my experience revealed it always seeming to reside with dealers who graded their cards several grades above what I could see with my own eyes. One of the most well known dealers with a larger presence at the show had one in a bargain bin that advertised all cards were priced 40% off sticker. I found an Ashburn with rounded corners and the typical centering issues and flipped it over, expecting a price that would put in line with the grade. Nope. There was a $250 sticker on the back, making a Good condition card waaaaay overpriced at $150 after applying the discount. I asked the closest guy at the booth if the stickers were accurate and he seemed confused as to why someone wouldn’t be jumping at the chance to pay 4x what I thought the card was worth. I think we both agreed it was time for me to move along to another table.

I would like to attend the National at some point in the future. Given experiences like this at seemingly every card show I have attended in recent years, it will probably be a while longer before I consider making such a trip.

At some point last year I finally found what I consider a fair deal on a ’52 Topps Ashburn. This one is in Excellent condition, primarily getting its condition knocked due to centering issues. This looks many times better than the Chantilly example and was priced around the same level. I’m glad I waited.

This card can be found with varying shades of green in the background. The example in my collection is more on the teal side than the emerald green seen on most.