I am admittedly not a student of the defensive side of the game of baseball, preferring instead to watch sharply hit drives and sliding baserunners. My personal ranking system for position players significantly overweights the offensive side of the game. I do, however, sit up and take note when defensive ability requires poetry to describe what has been witnessed.

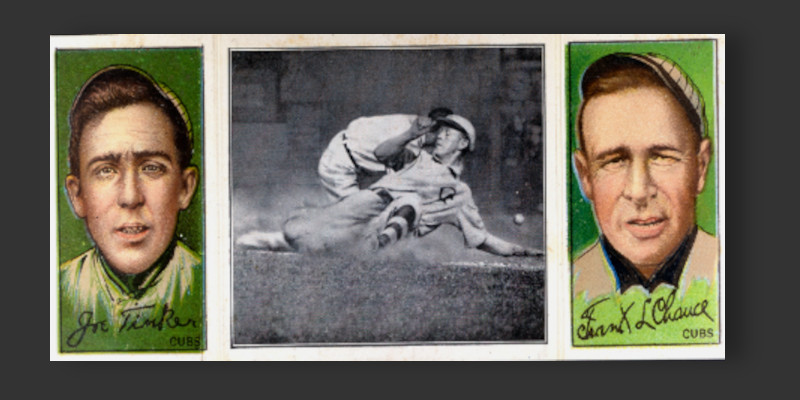

For a decade in the early 20th Century Cubs fans rejoiced at the infield wizardry of shortstop Joe Tinker, second baseman Johnny Evers, and first baseman Frank Chance. The trio frequently sat near the top of National League leader tables for the number of double plays turned. Franklin P. Adams, a noted columnist and future radio personality, lamented how often this trio of Chicago infielders dismantled the budding rallies of his New York Giants in the poem Baseball’s Sad Lexicon. The work was published in a 1910 edition of The New York Evening Mail and quickly caught on for a repeated line describing how promising New York hits quickly turned into multiple outs: “Tinkers to Evers to Chance.”

As the second-best known line of baseball prose behind “Might Casey has struck out,” Tinkers to Evers to Chance brings to mind the idea of record setting quantities of double plays. While double plays happened with regularity in the Cubs’ infield, other teams frequently bested the trio’s output during the era. Part of the reason was that Cubs pitching was generally pretty good. In order to start a double play you need at least one runner already on base.

Four decades later a team would arise that allowed baserunners at an elevated rate. The Philadelphia Athletics had by that time drifted far away from their legacy as perennial champions with strong pitching. Gone were the likes of Rube Waddell, Chief Bender, Eddie Plank, and Lefty Grove. Replacing them was a torrent of short-lived pitchers coming out of the team’s minor league affiliate in Ottawa. The 1952 Topps checklist is full of players of this caliber wearing A’s hats, with names like Bob Hooper and Johnny Kucab.

These middling pitchers of Connie Mack’s teams were offset by an infield dotted with stellar defensive ability. Heeney Majeski held down third base. Eddie Joost was at short. Pete Suder (and briefly Nellie Fox) could regularly be seen at second base while the sure-handed Ferris Fain manned first base. Broadcasts covering the action of the Athletics began to be peppered with the phrase, Joost to Suder to Fain.

In 1949 the Philadelphia infield produced a record 217 double plays, far exceeding the highest marks of Tinkers to Evers to Chance. No team has ever exceeded this total. In fact, only ten teams ever eclipsed 200 in a season, three of which were the 1949-1951 Athletics.

The quickness of Eddie Joost was surely a component of these double play marathons, as was excellent fielding by Fain at first. The fulcrum on which these plays unfolded was Pete Suder, the man in the middle of the action at second base. To successfully turn a double play, a second baseman must quickly make his play and accurately fire the ball to first. Oncoming runners try their best to disrupt the play, and by disrupt I mean physically hit the second baseman or use their body to block his throwing lane. With well over 600 chances to break up a double play in those three years Suder was undoubtedly hit hard on multiple occasions. Long after hanging up his glove, Suder was proud of never having been knocked off his target in any of these attempts.

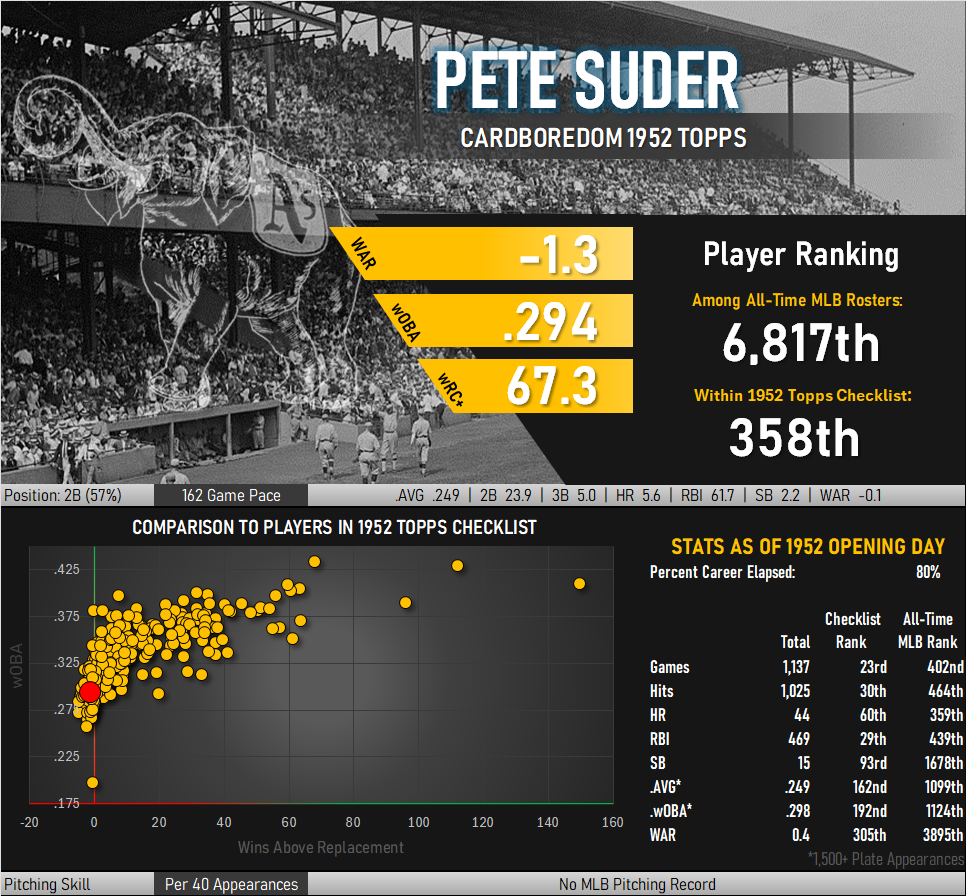

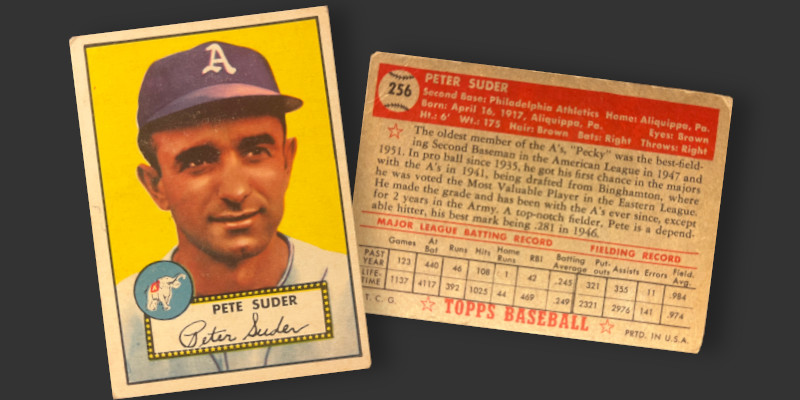

The text on the back of Suder’s 1952 Topps baseball card generously describes him as “a dependable hitter.” His contribution to the team was entirely on defense with his baserunning and batting skills actually producing negative wins above replacement even after factoring in his defense.

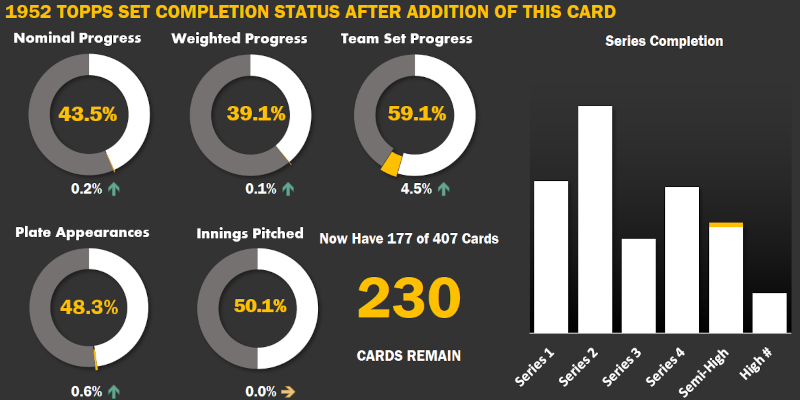

My first copy of this card was added to my collection as part of a collection of eBay transactions from a seller offering shipping discounts for bulk purchases. The card was one of the rougher examples in my set building project, so I took the opportunity to replace it with this one 18 months later when the opportunity presented itself.

Fun fact: Joe Tinker and Johnny Evers generally hated each other. The pair once got into a fistfight because Tinker wouldn’t share a taxi with Evers to a 1905 ballgame.