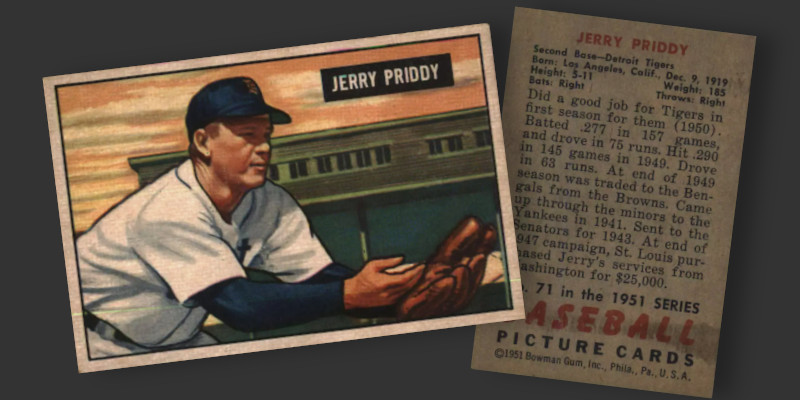

Let’s step back a moment and admire one of the best looking cards of the 1950s. Jerry Priddy’s card in the 1951 Bowman set is simply fantastic. There is the very identifiable roofline of Detroit’s Briggs Stadium Henley Park, Detroit’s spring training facility, in the background and is set against a very colorful Tiger-orange sunset. A horizontal layout allows Priddy to be seen ready to receive a throw, a pose that fans of the time would immediately associate with the defensive standout. The artist painting this card did good work.

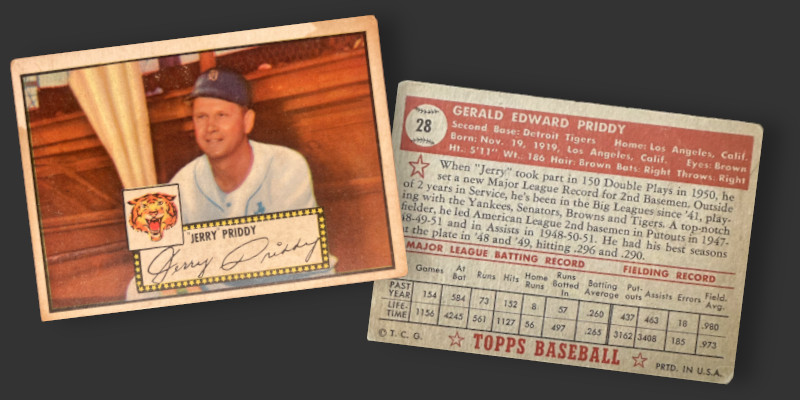

Priddy wasn’t a one-card wonder: He had multiple good looking cards across an 11 year career overlapping the return of postwar baseball card production. Like the Bowman example, his 1952 Topps card makes good use of a horizontal orientation. The Topps card borrows a popular Priddy photo in which he is holding five baseball bats near a stadium wall. The presence of chicken wire behind him only adds to the era-appropriate vibe. For some reason this photo makes me want to call him “Jerry Five Bats,” even though it makes him sound like a low level criminal. The name just seems to fit.

The back of the Topps card starts off with rather prominent quotation marks around the nickname “Jerry,” as if to follow the shortened name with a vaguely accusatory “…if that is your real name.” The bio goes on to talk up his defensive exploits, highlighting a record setting 150 double plays turned as a second baseman in 1950. The feat is even more impressive considering how little Detroit’s pitching set the table with walks and has only been beaten once in the ensuing 7 decades. Bill Mazeroski was able to record 166 double plays but did so in a longer season. Both are at least a couple dozen ahead of Robinson Cano’s 136 in 2007, the largest total in the present century.

Mazeroski made it to Cooperstown on the strength of his glove and an unforgettable World Series home run. If collectors are impressed with Mazeroski’s cards, perhaps they should take a closer look at those of his American League counterpart.

A Stack of Books

At some point in the early 1990s, my parents noticed my growing obsession with all things baseball and decided to give me some books on the subject. Nicholas Dawidoff’s The Catcher Was a Spy was a superb telling of the story of Moe Berg. Bobby Bragan’s whitewashed memoir was decidedly less enthralling. Perhaps most memorable is the red white and blue cover of Bill James’ The Politics of Glory, a book that introduced me to looking beyond the stats presented on baseball cards and dispelled the mystique surrounding the Hall of Fame.

The book, later republished as Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame, sought to break out the factors that made enshrinement most likely. Working from this point and using historical case studies, James then attempts to create a framework for gauging active players’ odds of eventually making it to Cooperstown. I did not fully understand the intent of the book at that time. I agreed with James that the Hall’s selection process was flawed, but mistook his attempts to model that process as him putting forward his own ideas for a replacement system. Only upon a much later reading did I realize my mistake.

There was, however, a singular vignette that stayed with me from the first time I went through the book. James devotes an entire chapter to the diverging professional paths of Jerry Priddy and Phil Rizzuto, a pair of Yankee prospects who could have easily seen their careers switch places if not for a difference in temperament.

The discussion proceeds along these basic lines: Coming up together in the Yankee farm system, Rizzuto and Priddy formed one of the best double play combinations in the game. Both broke into the majors in 1941, but Priddy had the misfortune of playing behind Hall of Famer Joe Gordon in the team’s depth chart. This understandably limited his playing time, something that was quickly brought to management’s attention by the outspoken Priddy. He was traded to the Senators where he could be used in the starting lineup and put up respectable offensive numbers while demolishing defensive metrics. After another run-in with management, he was sent to the St. Louis Browns where he again performed well before repeating the process and precipitating a move to the Detroit Tigers.

While there was widespread accolades for his defense, there was nothing about his record that screamed “Hall of Fame.” James’ argument was that the same could have been said about Rizzuto, who was eventually elected by the Veterans Committee in 1994. Priddy was the stronger offensive force between the two, batting for higher average with more frequent extra base hits. In terms of defense, Priddy demonstrably played second base better than Rizzuto played shortstop. It was essentially positional scarcity (shortstops > second basemen) and the Yankee mystique that gave Rizzuto the edge decades after everyone forgot about the better player.

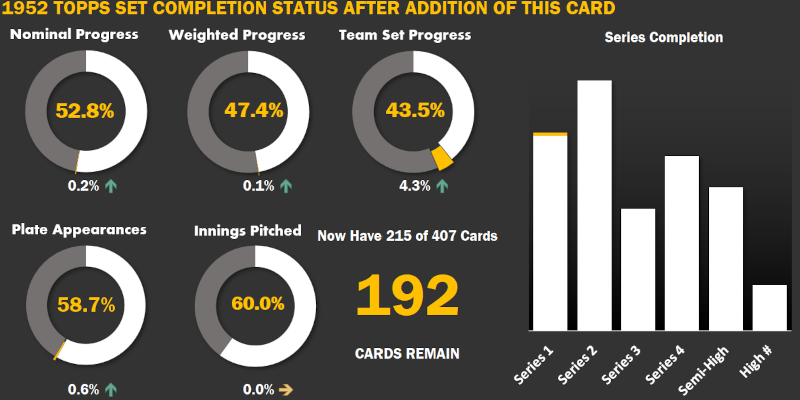

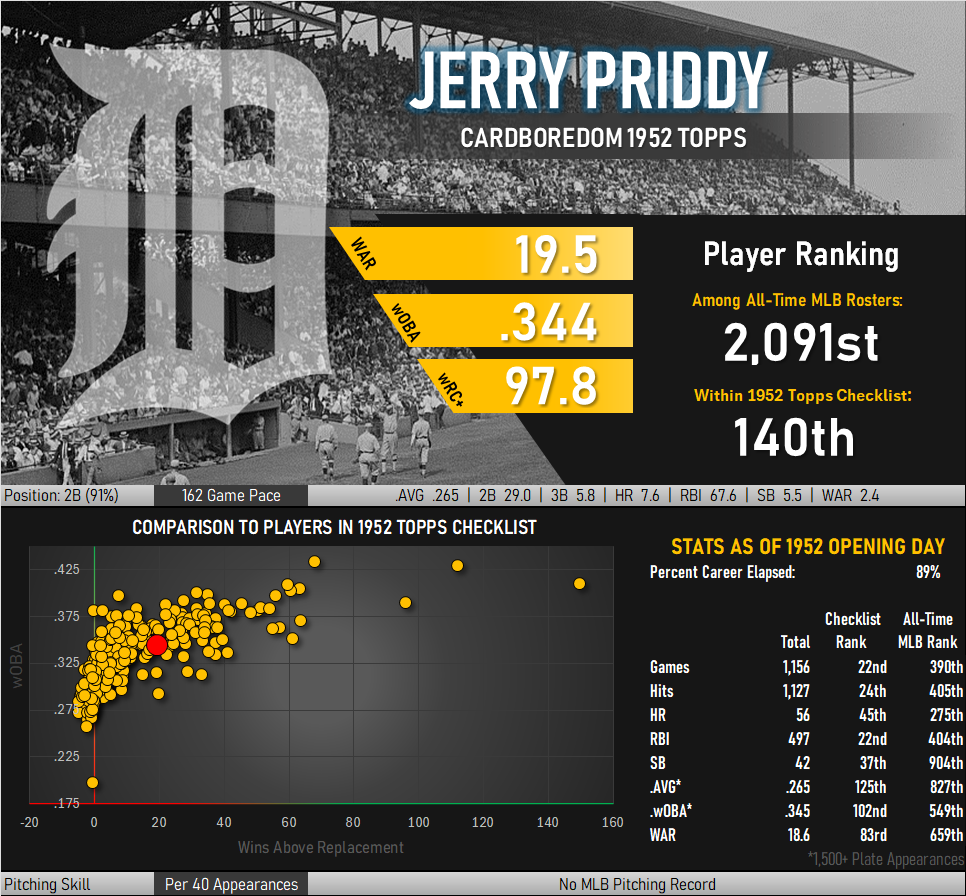

For the record, the graphic above should make it fairly clear that I do not think Jerry Priddy should be a member of the Hall of Fame. I do not value defensive skill as high as others and see Priddy’s vaunted offensive capabilities as merely approaching average. Besides, there is that pesky character clause to consider in selecting names for Cooperstown.

Throwing the Book at Jerry Five Bats

A midseason leg injury in 1952 (when he was leading the American League in doubles!) effectively ended his playing career, limiting him to just a handful of games the following season. He tried to recuperate in the Pacific Coast League but never made it, officially retiring from playing the game in 1956. As a rather outspoken member of multiple clubhouses, Priddy did not engender much sympathy. Asserting his place ahead of long-tenured (and highly performing) teammates while telling off those who underperformed alienated a lot of coworkers. This approach probably contributed to the brevity of his stint as manager of a PCL team. In 1973 things turned for the worse as a sharp recession began to bite and Priddy reached for his telephone.

Here’s what news reports capture:

The Island Princess made headlines when it pulled into Los Angeles early in the year and began operations as the largest cruise ship to be home ported on the West Coast. On June 5th the ship was underway to Puerto Vallarta with between 850 and 900 passengers and crew. At noon the Princess Cruise Lines Wilshire Avenue office received a message from an anonymous caller claiming multiple bombs had been placed aboard the ship. For the sum of a quarter million dollars, the caller offered to provide the cruise operator with the locations of the devices so they could be disabled. A series of phone calls ensued, with the caller making regular check-ins with Princess and the cruise line in turn looping the ship’s captain and the FBI into events. The ship’s crew conducted a full search of the vessel, identifying a pair of 4-inch, paper-wrapped cylinders tucked away on the bridge and in the engine room. The captain ordered the devices thrown overboard.

Meanwhile, the requested $250,000 was procured and placed into a trash can as instructed by the caller. A man stepped out of a nearby building, picked up the cash, and was immediately handcuffed by waiting law enforcement who had staked out the drop. The man literally holding the bag was Jerry Priddy.

With Priddy in custody and the devices sinking somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, the Island Princess continued onward to Mexico and allowed passengers to resume evening activities. A trial took place six months later in which Priddy admitted to making the calls and collecting the extortion payment. His defense rested on the claim that another anonymous caller was forcing him to carry out these actions with any deviation resulting in harm to his family. The jury quickly disregarded this story, returning a guilty verdict the same afternoon. The judge was more merciful, assessing a prison term of less than a year for charges that could have resulted in a decade behind bars.