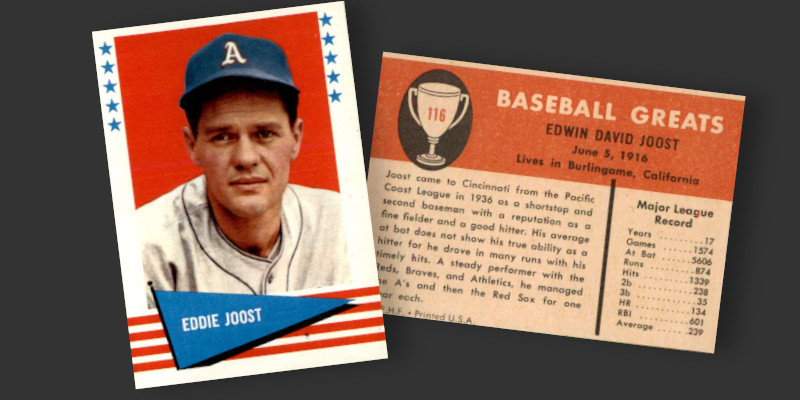

Eddie Joost looks a little perplexed on a baseball card issued by Fleer in 1961, the first piece of cardboard to feature the longtime shortstop after his 1955 retirement. Titled “Baseball Greats,” the set highlights retired players who carried vaunted positions in the history of the game. The checklist includes obvious candidates for such a collection, such as Ruth, Cobb, and Wagner. Other high level but somewhat overlooked players are included as well, like Dolf Luque and the sport’s second Dutch Leonard. Joost being included in the same lineup would produce a confused look on just about anyone’s face.

My first thought as to why Joost appears in the set is that he was one of the more popular members of the Philadelphia Athletics. The Fleer Gum Company was based in Philadelphia, and I presumed there were several die-hard Athletics fans in the building when plans for the set were drawn up. There was more to the story than just home team fandom, though his place in the sport is probably best recognized by A’s fans.

In 1961 the Fleer checklist was assembled by someone who really knew the game, highlighting not only those with the most impressive statistics but also names who were known as fantastic managers or as providers of elite defense. Joost joins as one of the latter with his .239 lifetime batting average beating out only Billy Sullivan’s .213 for the ranking of batter least likely to get a hit in the set.

OK. Based on the stats on the back of this card I would have disagreed with Fleer’s editorial staff when they described Joost as “a good hitter.” However, batting average isn’t everything and Joost was actually a unique player in the game.

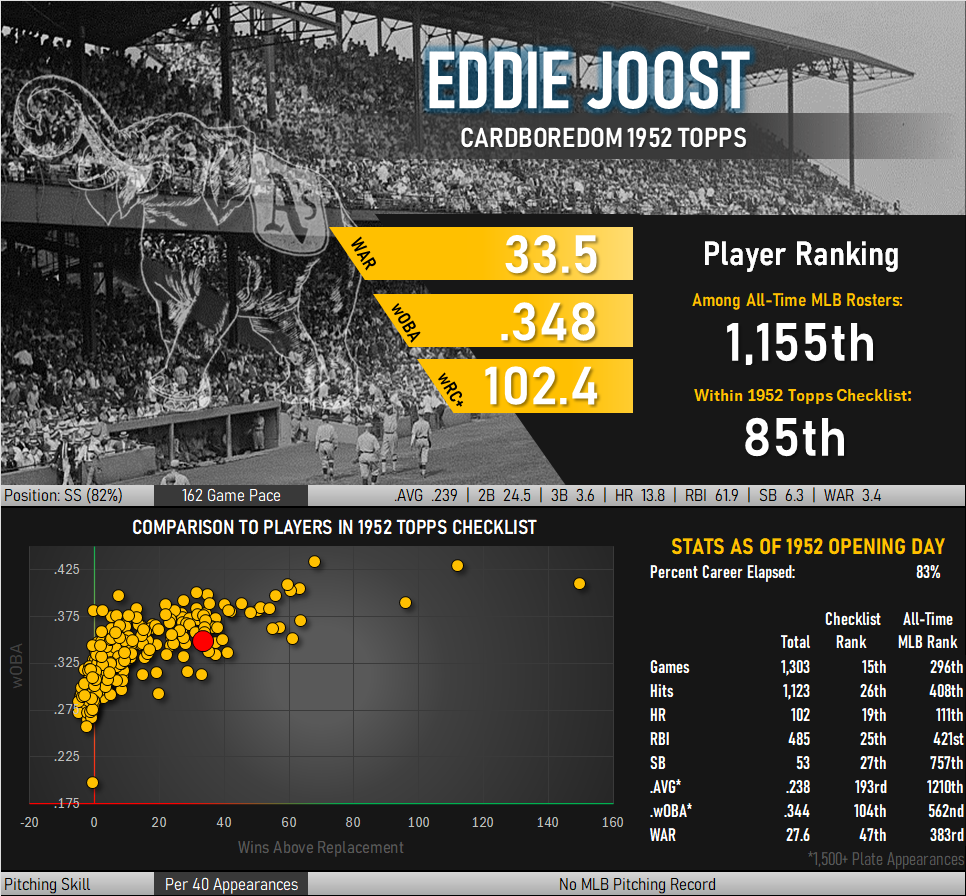

While he batted just .239 (and .233 excluding one outlier season) he managed to get on base at an amazing clip. The owner of one of the worst batting averages in the game carries an on base percentage of .361. That’s better than Don Mattingly. Better than Kirby Puckett. Better than Cal Ripken. Better than Roberto Clemente. It is better than at least four dozen members of the Hall of Fame. Eddie Joost, who seemingly never hit the ball and couldn’t even see it due to near-sightedness, was more likely to get on base than a literal busload of Hall of Famers.

While he did string together more than 1,300 career hits, Joost accomplished much of his on-basemenship (is that a word?) by being incredibly patient at the plate. He walked more than 1,000 times in his career, an impressive feat considering pitchers were in no way scared of his bat. That’s more than 17 miles of walking to first base.

The few hits that he did have seemed to travel well, as he averaged double-digit home run totals per 162-games played and generated a weighted on-base average of .348, better than Cal Ripken or Lloyd Waner. Waner’s path crossed Joost on the way to Cooperstown, as “Little Poison” Waner beat out a slow rolling ground ball hit to Joost for his 3,000th hit. Waner didn’t want to be known for getting to 3,000 with such a disappointing hit, so he tried to get the official scorer of the game to change it to an error on the part of the sure-handed Joost.

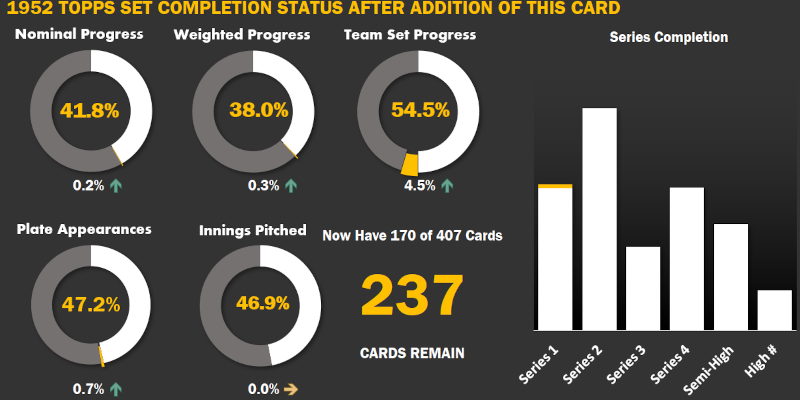

It’s clear Joost’s offense was several steps ahead of what his batting average would suggest. However, it was his defense that really set the tone. The 1940s were known for exceptional defensive play in the middle infield, lifting players like Phil Rizzuto and Pee Wee Reese to the Hall of Fame and generating kudos for equally good glove men like Gerry Priddy. Joost was among these names and set a record for taking part in double plays that still stands nearly 80 years later. Defense and those ever present walks to first created 3.4 wins above replacement per year, a rate better than Mo Vaughn, Gil Hodges, or Dave Winfield. As the chart above and the 1961 Fleer Baseball Greats checklist clearly show, Joost was a prominent member of the Hall of Very Good.

Joost managed for a couple years, serving one year stints as skipper with the Athletics and a Red Sox minor league affiliate before leaving the game for good. He had long developed a reputation for speaking his mind, a characteristic that can quickly make things really good or really bad for a manager. He fell into the role of managing the Athletics by accident: The team fired the previous manager and simply selected the current player with the highest salary to be his replacement. The A’s finished 51-103 during his tenure, beating out the 52-102 record that led to Connie Mack’s surrender of the managerial reins after 50+ years. Used as a player-manager, Joost batted .362 in limited action. The player famous for an absurdly low batting average hit for a higher average than his team’s overall winning percentage.

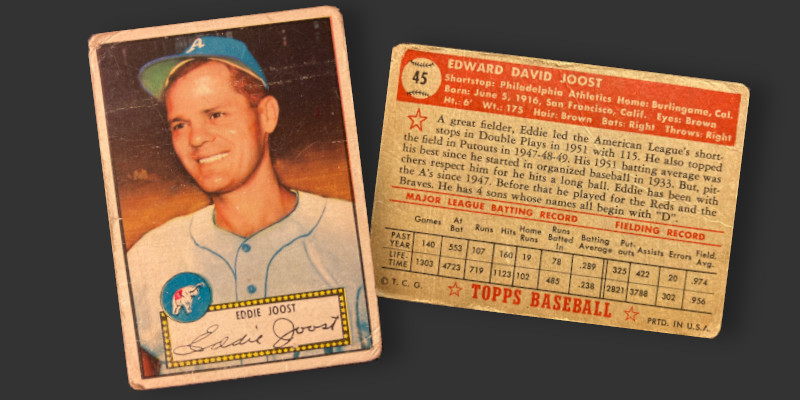

1952 Topps Eddie Joost

Joost is smiling broadly in the 1952 Topps set, as he should be. He was coming off the best year of his career, having hit more than 50 points above his career average, scoring more than 100 times for an offensively challenged team, and in general setting career highs in many categories. He made the All-Star team that year, and hit a game winning, bottom-of-the-ninth grand slam off of Satchel Paige in July.

All in all, the ’52 Topps set was a good one for guys named Eddie with extremely high on-base percentages. Eddie Stanky and Ed Yost join Joost as representatives for a style of play that would become more popular with statistically-inclined fans several generations later.

My card is among the more beat up ones in my collection. It has almost symmetrically rounded corners, some rubber band damage on the borders, and a few creases running through the top of the card. I’m a sucker for combined shipping charges and sub-$5 card prices. I had the same look on my face as Joost when I added it to my set building project.

As an aside, the ’61 Fleer Eddie Joost is an absolutely fantastic looking card. Featuring a colorized black & white photograph, the color artist’s work completely surpasses the work appearing on Joost’s 1952 Topps card. The design is amazing, and there exists an equally impressive blog chronicling a collector’s attempt to assemble an autographed set. Go check it out via Cardboard Catastrophes.