Around the same time I began chronicling my baseball card collection I picked up the habit of keeping a few of them in my wallet. I selected a handful of cards that had some sort of connection to my first brush with the hobby and let them accrue a few memories (and creases) as the accompanied me wherever I went. When 12 months had elapsed I selected three more cards to take their place and repeated the process. The goal was to take cards that traditionally have gone straight from packs to protective top loaders and instead subject them to the same wear and tear seen on the cards from 50+ years ago. Staring at those vintage cards, you just know they had stories to tell about where they had been. I decided to create some stories of my own.

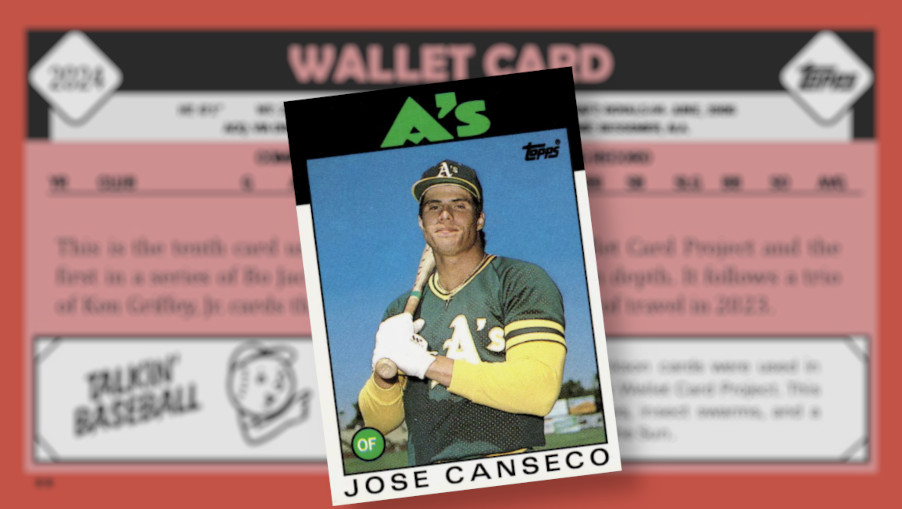

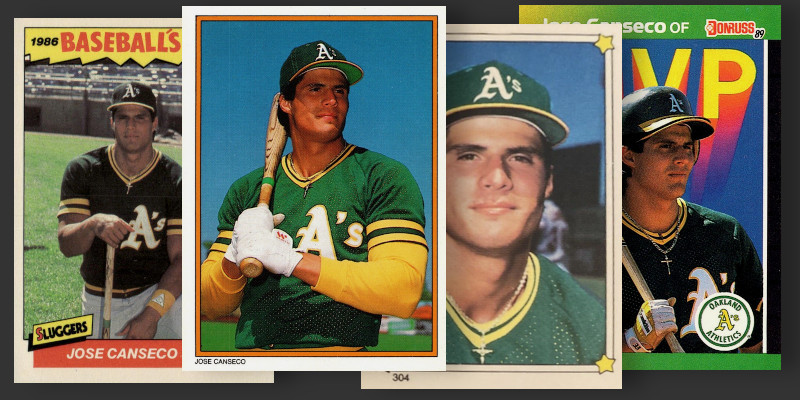

I kicked off this project with my three favorite Jose Canseco rookies in my pocket. Since then I have taken a closer look at the famous Rated Rookie and the decidedly non-descript ‘86 Fleer Update. Now it is time to examine the final 2021 Wallet Card: The end of season 1986 Traded release in which Topps tried to avoid being shut out in the ongoing race to carry the most sought after rookie cards.

Setting the Stage

By 1986 the hobby of collecting baseball cards was booming. Fears of an industry collapse brought on by the breaking of Topps’ monopoly proved unfounded with more cards being purchased than ever before. Topps was still the undisputed king of baseball cards, but improved products and a newfound focus among collectors on rookies provided an opening for Fleer or Donruss to shift the hobby’s mindset. Topps was on top because it had dominated for so long with newcomers were seen as interlopers in the market for “real” baseball cards.

However, a growing hobby meant lots of new collectors with cash to spend. These collectors were seeing all three brands more or less for the first time, meaning Topps’ hobby inertia was not nearly as strong among those providing incremental dollars to the hobby. These collectors were a new breed, eschewing many of the traditional ways of collecting and focusing more and more on finding rookie cards of baseball’s next superstars. Omission of such a cardboard debut could lead to a manufacturer ceding market share to rivals.

Topps was good at this game. The company included Fernando Valenzuela in its 1981 set, the first year of competition with its rivals, and introduced its yearend “Traded” product line that season to ensure another round of callups got a Topps card in their rookie season. They again captured the Rookie of the Year winner in both the flagship and traded sets in 1982 and hit a hobby home run as the only producer to issue a Darryl Strawberry card in 1983. Topps repeated the process in 1984, releasing a Doc Gooden rookie. Whenever there a new rookie capturing everyone’s attention, Topps was there.

That is, until the 1986 American League race for Rookie of the Year came along. Wally Joyner unexpectedly replaced Rod Carew on the Angels’ roster, sending collectors searching for cards that did not exist when he hit 19 home runs through the end of May. Here was a rookie absolutely clobbering Roger Maris’ 1961 pace that had seen him hit 12 home runs in the same span, yet no major card manufacturer had included him in a checklist.

Joyner’s production tailed off after the All-Star break and he was surpassed for the award by a newly arrived Oakland outfielder. Between two levels of minor league ball and a 29 game callup Jose Canseco had hit .328 in 1985 with 41 HRs and 140 RBIs. Donruss and Fleer both made sure to include him in their checklists, prompting rookie-crazed collectors to wipe out wax pack inventories. Topps, on the other hand, omitted Canseco from its checklist and gave collectors a rookie card of the Oakland A’s Mike Gallego.

What happened? Perhaps Topps didn’t have a photograph handy.

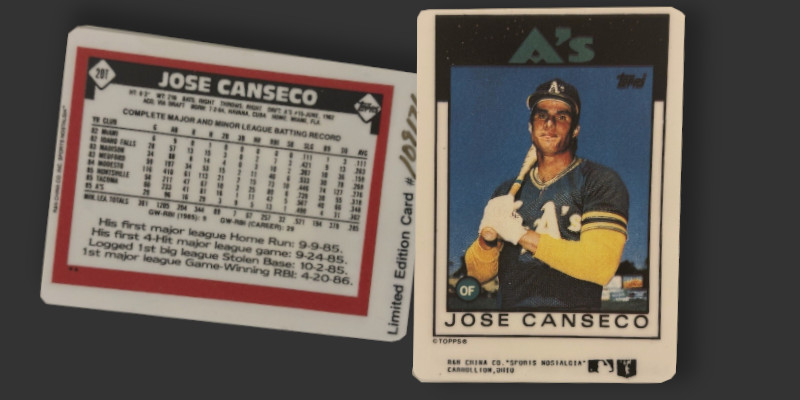

Looking at the Card

My theory for Topps’ swing and miss holds its origins in the company’s almost maniacal insistence on controlling its intellectual property and the schedules of the photographers under contract. Unlike Fleer and Donruss, which would take a while to develop relationships with photographers, Topps used many of the same contractors from year to year. In keeping with the company’s ethos, these annual photography assignments were set up as one year contracts and typically took place during Spring Training.

West Coast assignments were usually handled in three week stints for Topps by photographer Doug McWilliams. He covered the A’s 1985 Spring Training in Phoenix, and I assume did not capture an image of Canseco. The minor leaguer had never played above A-level ball to that point and it is possible that players of that level were not even present at the ’85 camp. Topps wasn’t going to pay for images it couldn’t use, and a .276 hitter coming out of single-A would not be a high priority.

McWilliams’ assignment concluded at the end of Spring Training and he would return to California for another year before trekking back to the ballparks of the Cactus League. Topps, meanwhile, spent the better part of the 1985 season selecting images from his work and placing them into the layouts for the next year’s crop of baseball cards. Checklist decisions were made in 1985 with the end product finalized at the turn of the year in order to meet production deadlines. Images captured in 1986 Spring Training would be too late to make their way into 1986 wax packs as wholesale deliveries were timed to coincide with the excitement of prep for a new season.

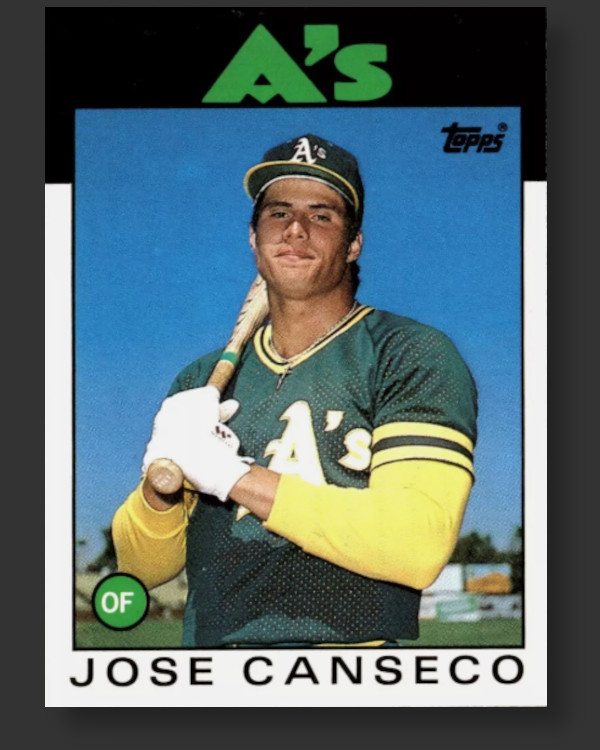

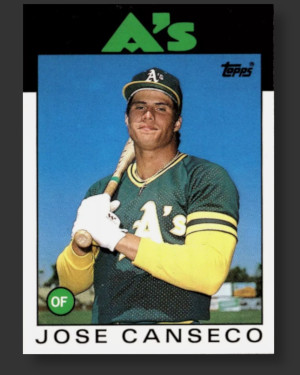

Topps caught up with Canseco in 1986 Spring Training and released this card as part of the Traded set at the conclusion of the season. I suspect McWilliams captured the image, which appears to have been taken in Phoenix Municipal Stadium given the double decker outfield billboards, distinctive left field bleachers, and the sparse tree line visible just over the wall. He is posed along the third base line, possibly within his familiar right hand batter’s box. The photographer likely positioned him there to take advantage of the Arizona sky backdrop and at that specific angle to block out the light towers beyond the left field fence.

Topps almost missed Canseco again, as he held out reporting to camp for a brief period in a bid to have his 1986 pay increased to $100,000 (he settled for $70k). The strongest lighting is coming at a high angle from the southwest, indicating the photograph was captured in the early afternoon rather than the morning. With temperatures eclipsing 90 degrees at the beginning and end of the month, Canseco’s yellow long sleeves stand out as more than just a fashion statement. A clue to the date of this image can be found in Phoenix weather records, which indicate thermometers topped out at an unseasonably cool 62 degrees on March 14 with similar readings on nearby dates.

The yellow sleeves are not the only fashion captured in the image. Around Canseco’s neck is a gold crucifix. The same piece of jewelry can be seen on his 1986 Fleer Baseball’s Best Sluggers and 1987 Topps Mail-In Glossy, and 1989 Donruss MVP cards as well as his ’87 Topps Album Sticker. The ’87 Glossy is almost certainly from the same photo shoot as the ’86 Traded.

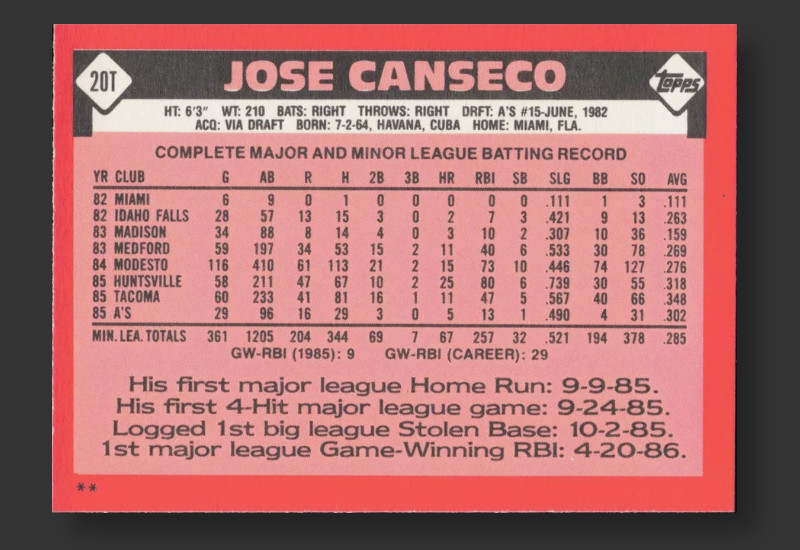

The back of the ’86 Traded card offers a glimpse into several interesting threads. The top of the card is primarily concerned with the standard baseball card demographics: Bats right; throws right; born in Cuba, etc. Canseco’s weight was a bit in flux during this time, as can be attested by his rookie cards. Donruss reported him to be 185 lbs., Fleer said 195, and Topps claimed 210. Newspapers covering 1986 Spring Training reported him leaving camp at 228 lbs. Confusion was the order of the day, with Fleer revising its estimate down to 185 for its Update series and Donruss matching Topps at 210 lbs. in the latter’s The Rookies yearend boxed set.

Aside from using Canseco rookies as a random number generator, another thing jumps out. The text at the bottom of the card reports Jose recording his first major league Game-Winning RBI on April 20, 1986. Not only is it interesting to see a card report on happenings from the same year in which it is printed, the note highlights a shift taking place in the game itself. New statistics were just starting to make their appearance, as were fantasy baseball and the SABR-crowd. Many of the early statistics sounded like they might yield actionable insights, though further study revealed them to be about as useful as batting average or pitching wins. However, this willingness to expand beyond the traditional baseball card stats was pointing at what was to come.

Game-Winning RBIs was one of the new metrics briefly in vogue during the 1980s. Major League Baseball began officially compiling the stat in 1980, crediting whatever batter recorded the RBI that gave a pitcher the W in a victory. Topps really wanted to make this a thing, including the stat as both a single season and career total just below the table of statistics on position players’ 1986 cards. The card mentions Canseco’s first GW-RBI, but does not give a total for 1986. That is unfortunate, as he and Wally Joyner both set the MLB record for GW-RBI by a rookie that year. Mark McGwire would tie the mark in 1987 and MLB would abandon compilation of the stat one year later.

Production and Distribution

The only way to get this card in 1986 was to visit your local card shop or the odd retailer or two who stocked end of year boxed sets. This was not a tall order, as the number of dedicated hobby outlets had exploded by the middle of the 1980s. While a few standalone retail locations and a good number of mail order dealers represented the hobby in the previous decade, the number of dedicated storefronts alone topped 10,000 by the end of the 1980s. Many of these were already in operation when Topps was marketing its year end ’86 Traded edition cards to shop owners in increments of 100-set cases.

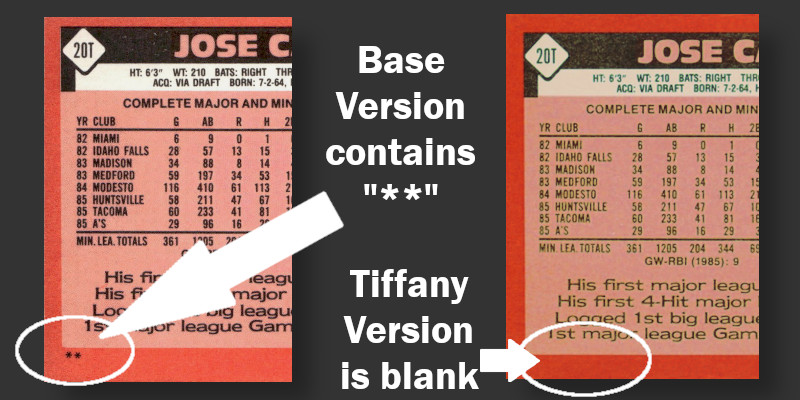

This indicates no shortage of finding any particular card from the ’86 Traded set, but what kind of print run are we actually talking about? Topps did not publicly release production numbers for this set, but the manufacturer did serial number a parallel special edition of the cards out of 5,125 produced. Known within the hobby as the “Tiffany” edition, they command quite the following and generate significant interest when one becomes available.

For example, there are 33 legitimate Tiffany versions of the set’s Barry Bonds rookie available right now on eBay. Given the popularity of both Bonds’ Tiffany and base cards, it would follow that some sort of estimate of base ’86 Traded cards can be inferred by comparing the number of Tiffany cards with the quantity of base cards concurrently advertised. There are 2,987 base Barry Bonds cards listed for sale against 33 Tiffany examples, implying base cards have a print run of 90x higher. From this an estimate of 463,890 of each ’86 Traded card can be constructed. Let’s round this to ~500,000 of each card in the set, so there are roughly a half million ’86 Traded Canseco cards out in the wild. It’s a fairly easy card to find.

A Whole Lot of Smirks

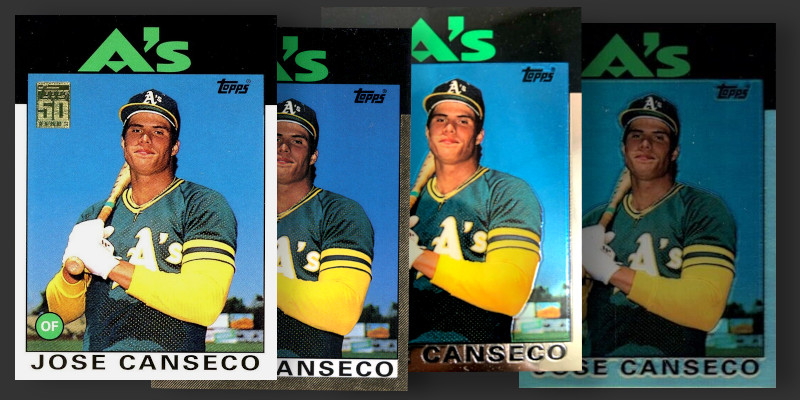

Perhaps Topps thought 500,000 copies wasn’t enough. Classic cards show up again and again, and by my count there are now around 70 different versions of this smirking card, including the original.

By far the most sought after version of the card is a parallel marketed concurrently with the Traded set in 1986. Advertised at the time as the “Collector’s Edition,” the card is more commonly known as the “Tiffany” edition. Tiffany versions of ’86 Topps Traded appear nearly identical to their base counterparts, save for much richer gloss on the front of the card and the lack of a pair of asterisks on the back. Like the base versions, these were distributed only as complete sets in hobby outlets. Just over 5,000 Tiffany sets are thought to exist.

Topps released a short-lived product entitled “DoubleHeaders” in 1989. As the name implies, these were two-sided color baseball cards and were designed to be displayed in a double-sided plastic stand allowing both sides to be easily viewed. One side pictured a player’s 1989 Topps base card and the other featured a reproduction of his Topps rookie. Canseco was one of 24 players in this release. A follow up edition appeared in 1990 pairing the new crop of Topps base cards with reproductions of rookie cards.

Oddball rookie reprints were quite a fad during this period. From 1990-92 a series of oversized porcelain reproductions of assorted baseball cards were offered in various newspaper advertisements. Those who took up the offer purchased a recurring subscription in which these “cards” were delivered by mail on a monthly basis. Canseco’s 1986 Traded card is among one of better known components of the issue.

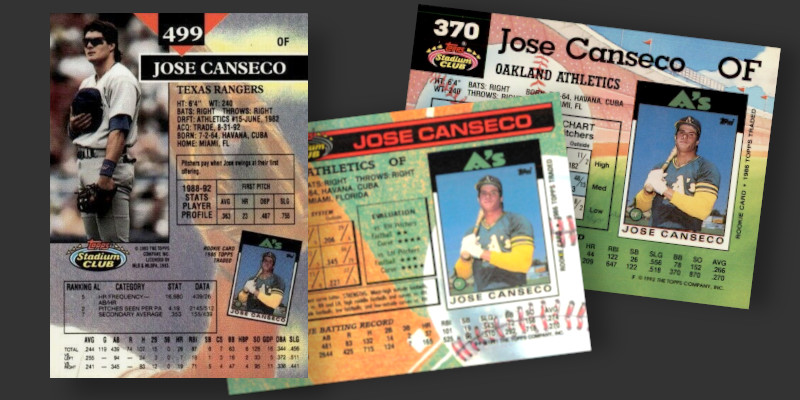

Rookie references continued in the early 1990s. Topps released its Stadium Club product line in 1991. The first three years of these cards leaned heavily on featuring a reproduction of each player’s rookie card on the back. The 1993 edition (pictured on left) saw the prominence of this design element reduced before it was eliminated entirely from 1994 onwards. Both the ’91 and ’92 editions are available with variations in the text on the copyright line. The ’93 comes in a base version as well as “Member’s Only” and “First Day Production” parallels.

The reprinting of this card got out of hand after the turn of the century. 2001 Topps Rookies & Traded, for example, included reprints in base, gold, chrome, and retrofractor versions.

The number of parallels and frequency with which this card is resurrected increased with time. Rather than track down images of what is essentially the same card over and over again, I will leave you with this checklist:

| Year | Set | Version | Autographed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | Topps Gallery Heritage | No | |

| 2003 | Topps Gallery Heritage | Relic (Bat) | No |

| 2003 | Topps Shoebox Collection | No | |

| 2004 | Topps Originals Signature | 1/1 Buyback of Original | Yes |

| 2015 | Topps Archives Signature Series | Yes | |

| 2016 | Topps Archives Signature Series | All-Star Edition | Yes |

| 2017 | Topps Archives | Originals Autographs | Yes |

| 2017 | Topps Clearly Authentic | Auto Reprints | Yes |

| 2019 | Topps Update | All-Time Great Redemption | No |

| 2020 | Topps Rookie Card Retrospective | Medallion | No |

| 2020 | Topps Rookie Card Retrospective | Medallion Autograph | Yes |

| 2020 | Topps Rookie Card Retrospective | Black | No |

| 2020 | Topps Rookie Card Retrospective | Gold | No |

| 2020 | Topps Rookie Card Retrospective | Platinum | No |

| 2020 | Topps Rookie Card Retrospective | Red | No |

| 2022 | Topps Archives Signature Series – Retired | Yes |

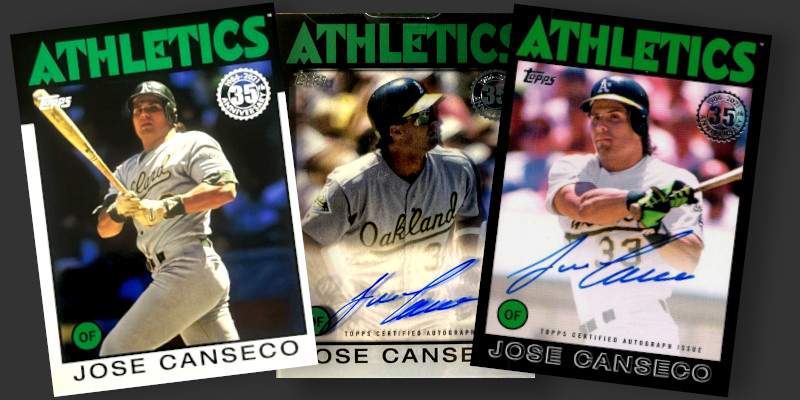

Those are just the cards that purport to look like the original ’86 Traded card. Topps issued multiple 35th Anniversary retrospectives in 2021 in which modern and retired players were depicted on designs inspired by 1986 Topps. Canseco appears in both the Topps and Clearly Authentic 35th Anniversary sets. Including base versions, there are 25 different editions of the Topps card to collect and 8 from Clearly Authentic. For good measure Topps included another 5 variations of these cards with 2021 Topps Update.

Even cards initially envisioned as looking nothing like an existing item sometimes went back to the well for inspiration. Topps commissioned three different artists to produce a trio of Canseco cards for the 2021 edition of its Project70 line of cards. Streetwear designer Don C reimagined the Cuba to Miami baseball transplant’s ’86 Traded card as the movie poster to Scarface. I can’t think of any other player where this would have worked so well.

Trading For a Traded Card

I grew up wanting one of the original ’86 Traded Canseco cards but did not obtain a copy until I laid out my wallet card plans in 2021. That doesn’t mean I didn’t have a plan for obtaining one if a trade was possible.

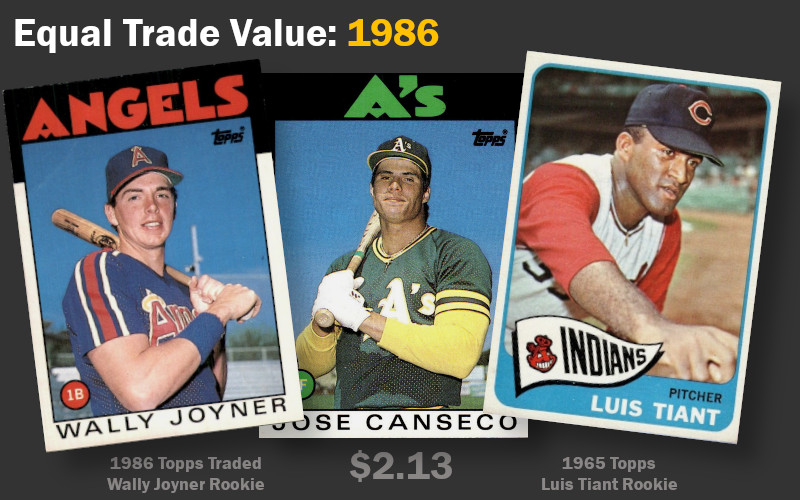

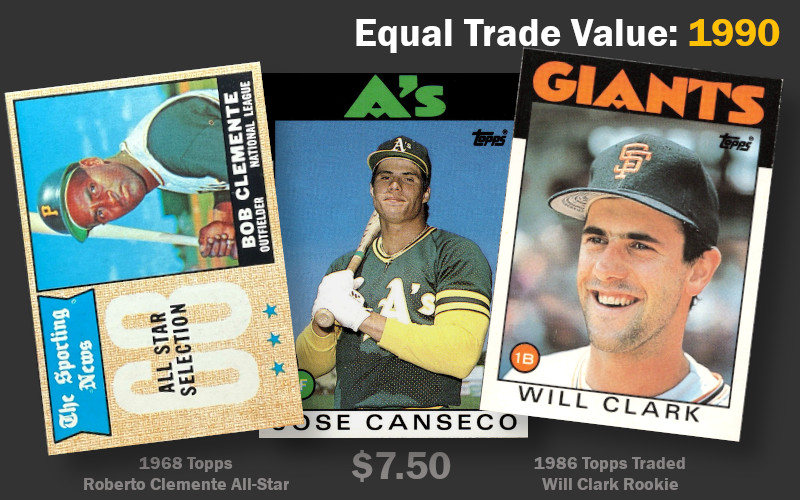

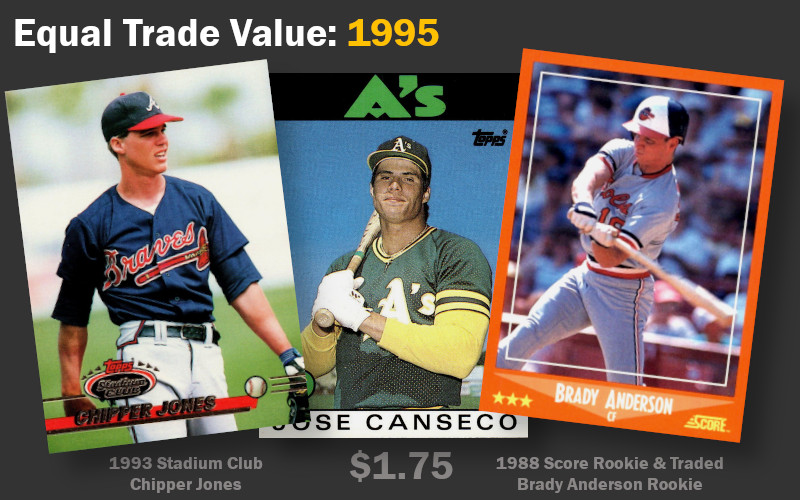

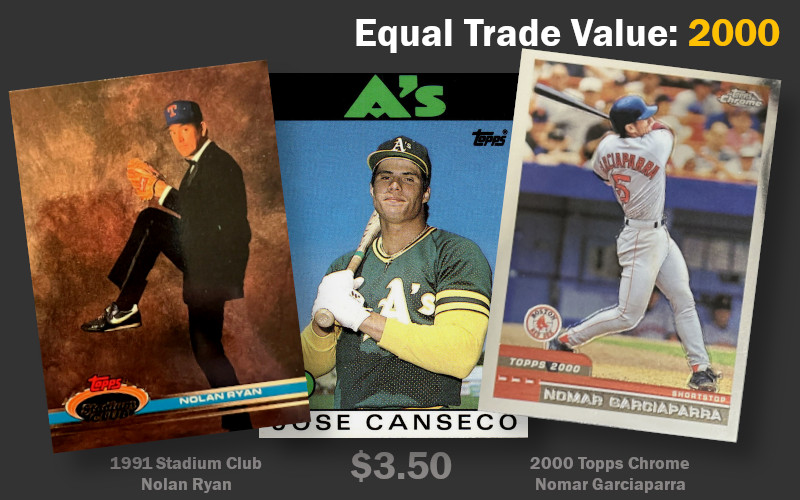

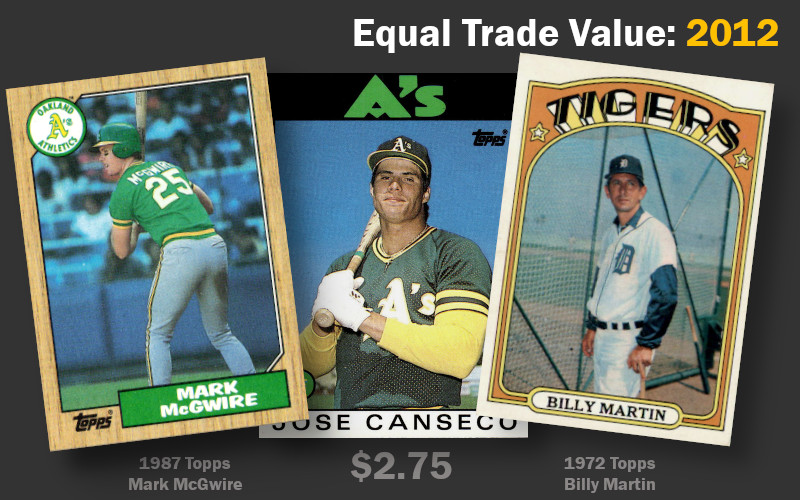

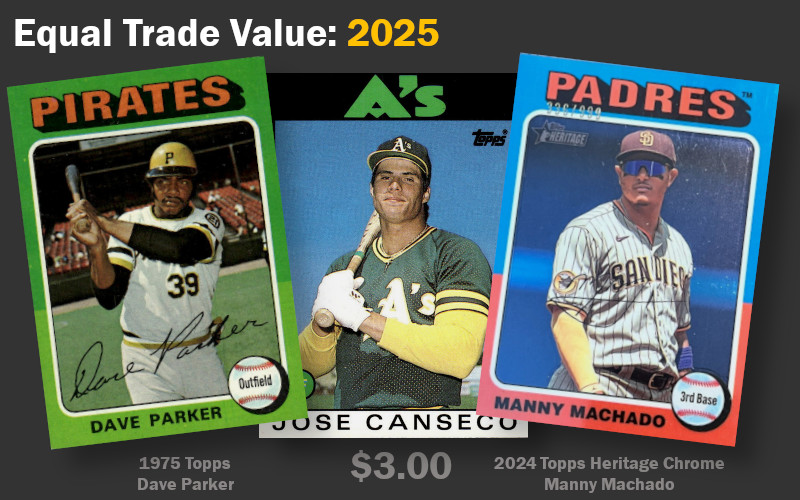

The one overarching trading rule within my group of friends was that any trade to be contemplated had to involve equal value for all parties. The most recent Beckett price guide was the arbiter of value, though Tuff Stuff was employed in rare instances. Appearing below are examples of plausible trades through time that would have passed inspection of any kid willing to trade by those rules. Prices indicate the average high and low values reported in end of year price guides.

The home runs of Wally Joyner and Jose Canseco provided the fuel for the 1986 rookie card chase. Both received their first Topps cards with the release of the Traded set and their respective pieces of cardboard were considered interchangeable. This was on par with what you could expect to exchange for early vintage cards of guys who sort of inhabited the no-man’s land of the Hall of Very Good. Many of these were only a single generation away from having been pulled from packs, making it the kind of trade someone’s dad might make if looking to exchange one of their childhood cards for one of the modern guys being collected.

A few years later Canseco was no longer a prospect, but one of the biggest names in the game. Anyone trying to exchange their old cardboard for one of his rookies now needed a top tier name to swing a deal towards completion. The in-demand Rated Rookie from Donruss could command a card of Sandy Koufax or Roberto Clemente in exchange. Seen as part of a less desirable set, owners of the Traded Canseco could still nab of these top flight players if they were willing to look at vintage All-Star and league leader cards.

By this time other parts of the 1986 rookie class were vying for MVP awards. Will Clark and the San Francisco Giants had just battled an earthquake and Canseco’s Athletics in the 1989 World Series. Clark’s ’86 Traded card saw just as much demand as his rival across the bay.

A decade after the card’s debut, Canseco had been part of three World Series, captured an MVP, became the biggest name in the game, and created the 40/40 club out of sheer hubris. All of this took place in a period in which collecting baseball cards exploded in popularity with price levels generally multiples of what they were in 1986. And yet, the ’86 Traded Canseco card could be readily had in 1995 for less than what one would have cost at the time of its debut. It seems everyone who wanted a copy already had one and there were no marginal buyers left.

Topps was taking no chances with the current crop of prospects nearly a decade after their omission from the 1986 base set. Not only were new releases filled with prospects who had yet to see a major league pitch, those names were now appearing across the full run of Topps’ expanding product line. Chipper Jones had multiple rookie cards in Topps’ 1991 products but would not lose rookie eligibility until the end of the 1995 season. That year collectors could expect to fork over a Canseco rookie if they wanted to obtain one of Jones’ numerous base cards from any part of that 4-year rookie purgatory.

Not every rookie appears to be a star when they make their cardboard debut. Brady Anderson’s career did not take off until 4 years after his cards first appeared in a similar yearend Rookie & Traded release in 1988. This set had seen lower demand than Topps’ issue and was printed in smaller quantities, lending a small scarcity premium to the names in the checklist. By 1995 Anderson had established himself as speedy outfielder who could steal 40-50 bases in a good year. Those that had an extra Canseco or two lying around might have considered swapping one out for this color-matched Oriole rookie. Such an exchange would have looked prescient the following year when Anderson inexplicably hit a Canseco-like 50 home runs.

At the end of the decade a Canseco rookie was good for a card of an upper tier player from an upper tier set. A 1991 Stadium Club Nolan Ryan tuxedo card? Sure. A Chrome Nomar Garciaparra freshly pulled from the current year’s release? Why not? Canseco was approaching 500 career home runs at this point and still capable of hitting 30+ bombs in a normal season.

Five years later Canseco had exchanged his day job of playing professional baseball for one involving publicity tours and book signings. With PEDs and baseball suddenly linked in the public consciousness, the now ex-baseball player was promoting his tell-all account of steroids in the game. It had been so out in the open by this point collector interest in this card barely registered any volatility in demand.

What was on the move were the cards of other players. Somewhat forgotten rookie cards of now-veteran late blooming players were catching up. Collectors had rushed to acquire Kal Daniels rookies in the late 1980s, only to abandon them when knee injuries cut his career short. The okayish outfielder appearing alongside him on his Fleer rookie needed almost a decade to turn into one of the key components of a resurgent New York Yankees club, bringing cards of Paul O’Neill back to the hobby’s attention.

The prospecting game was also alive and well at this time. Maybe this low-average Yadier Molina guy will turn out to be pretty good.

Want to trade infamous cards? By 2012 the last vestiges of PED-denial had come down. Mark McGwire confessed at least a decade of usage to the Associated Press in 2010. McGwire card owners collectively matched Canseco’s facial expression when viewing their cards, and suddenly the two seemed a bit more interchangeable. Those looking to escape the current controversy could go back in time for a more subtle sort of trouble. A collector favorite in the infamous card genre is Billy Martin’s 1972 Topps card depicting the Detroit Tigers manager quietly giving the photographer the finger.

These days you can find a decent ’86 Topps Canseco for about $3, about the going rate for a few other cards featuring team affiliations in similar block letters. Dave Parker was recently elected to the Hall of Fame and collectors can easily add his second year cardboard appearance from ’75 Topps (check out the Roberto Clemente memorial patch on his left shoulder). Like Canseco, Parker was a bigger than life personality that captured an outsized portion of the attention paid to his team. That may seem like a bit of a drawback in the later stages of his career, particularly after his involvement in the Pittsburgh Drug Trials. However, it was exactly what Oakland needed as the team geared up for three consecutive World Series appearances. The former hitting champ’s bat protected the Bash Brothers against intentional walks, forcing opposing pitchers to sweat out inning after inning. His personality protected them in the clubhouse, where he would be strategically outspoken to draw media attention away from McGwire and particularly Canseco whenever they were close to creating unneeded publicity. The veteran presence of a guy who knew firsthand the pitfalls of fame and the fast life was also reassuring from a development standpoint.

Parker won accolades while also developing a bit of a reputation as a villain in some baseball circles. Today it is Manny Machado that unapologetically generates alternating cheers and jeers from the stands. Much of this can be attributed to the brashness of his first decade in the game, though with San Diego he seems to have settled into the role of a veteran leader taking younger stars under his wing. Though issued 50 years apart, these cards may have more in common than just their design.

Fun fact: Machado’s 342 career home runs at age 32 are just 9 behind Jose Canseco’s 351 at the same age. There may just be more in a Canseco/Machado comparison than just an affinity for yellow sleeves and wraparound sunglasses.