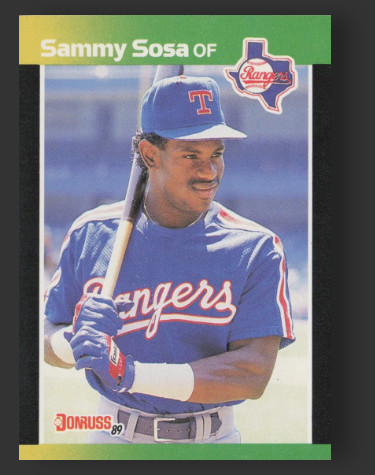

[Author’s note: Every year on my birthday I select a handful of instantly recognizable baseball cards to become “Wallet Cards.” The cards are always chosen with a theme in mind and are subsequently deposited for the next 12 months into my wallet. The cards are not encased in any sort of protective sleeve and quickly accumulate significant damage and wear. I document the before and after states of these cards and will sometimes keep a photographic journal of the adventures on which they have accompanied me. Each of these cards has its own story behind it, and at a later date I take them out and find out all I can about their history. This exploration of Sammy Sosa’s 1990 Leaf baseball card is the latest in this series.]

It seemed like everything was getting bigger as we moved into the next decade from the 1980s. Skinny jeans were replaced by MC Hammer’s parachute pants. Action heroes looked more and more like Arnold Schwarzeneggar instead of the leaner actors like Harrison Ford and martial artists such as Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris. Women’s hairstyles even briefly tried to outhair the male hairbands of MTV. Despite Dave Parker playing for both teams, the champion 1989 Oakland Athletics were taller and heavier than their 1979 counterparts on the Pittsburgh Pirates.

The same phenomenon was playing out with baseball cards. Topps began the 1980s with a 726 card checklist. By 1990 they had increased the base set to 792 cards and managed to get collectors to expect a further 132 card Traded edition to mop up checklist corrections and omissions at the end of the year. The company made things literally bigger with the introduction of Topps Big and a resurrection of the defunct Bowman brand, both of which hit shelves with cards of the same dimensions of larger pre-1957 baseball cards. It wasn’t just Topps producing cards, as the 1990s set off with base sets being produced by five major brands. Score took large bigness to heart, debuting in 1988 with full biographical writeups on the back of cards by 1991 was producing an 893-card base set to be augmented by a further 110 cards in the year end Traded edition.

Multiple new entrants were applying to MLB at this time for card production licenses. Upper Deck shocked (and quite delighted) collectors with the introduction of higher quality cards in 1989. The upstart’s debut set grew to 800 cards by the end of the season and sent competitors scrambling for an answer. Just making more cards would no longer cut it and everyone was looking for a way to step up their game.

Amazingly, it was Donruss that was the first to answer Upper Deck’s challenge. Already considered at best a second tier card producer, a strong sophomore showing from Upper Deck was sure to make them no better than third place in an increasingly crowded market. Donruss’ design team began working on ways to improve their products, going as far as to run experiments on their flagship cards to test the viability of new production techniques (see my 1990 Aqueous card for an example of this).

Hoping that Upper Deck would be a one hit wonder was absolutely out of the question, leaving Donruss with a few avenues to pursue in making its product lineup more competitive. Upgrading the manufacturer’s flagship offering came with two drawbacks: 1) It would be very expensive, significantly raising production costs with little likelihood of the lower level brand recouping the additional outlay through pricing power, and 2) It would be 1991 before any sort of retooling could take place. Upper Deck would steal a second year’s march on Donruss if the latter tried to compete with its base set offering as these cards are put to the presses at the end of the calendar year. By the time Upper Deck blew up in popularity it was already too late to reconfigure the content of Donruss’ bright orange 1990 wax packs. The solution would be to launch a totally new product, but how could this be done in such a way as to gain instant credibility and avoid the stigma of being an “oddball” issue?

Fortunately, a quirk of corporate history gave Donruss a valuable piece of intellectual property to work with. The company had long manufactured trading cards, focusing on non-sport entertainment subjects for much of its history before entering the baseball card market in 1981. Two years later the business was acquired by the Finish conglomerate Huhtamaki, which was in the midst of a North American confectionary acquisition spree. Donruss was one of several additions in the early 1980s alongside the several candy manufacturers. More additions followed, creating a candy behemoth turning out Jolly Ranchers, Now and Laters, and Milk Duds by the truckload.

So why was the marriage of a maker of third tier baseball cards and a collection of third tier trick or treating favorites so pivotal for Donruss? The centerpiece of the newly acquired candy business was Chicago’s Leaf Candy Company, a name instantly recognizable to baseball card collectors. As an independent entity in 1949, Leaf produced a set of cards that became a cornerstone of collecting, one held in such high regard that many in the vintage area of the hobby consider to be a more daunting challenge than the famed ’52 Topps set.

Leaf managed to get a partial set out its doors to collectors before having its cardboard ambitions destroyed by litigation. A second interrupted attempt to produce baseball cards met similar legal hurdles in 1960, seemingly consigning the Leaf brand to the history books. But now? The courts had thrown the gates to card production wide open. Donruss had now been a fully licensed card manufacturer for a decade and owned the famed Leaf brand outright.

And best of all, there were no competing claims on the brand’s usage.

Two years after its 1983 acquisition of Donruss, the candy manufacturer expanded its distribution into Canada. It did this in a similar manner to Topps’ longstanding partnership with O-Pee-Chee, producing baseball cards almost identical to their American counterparts sold under the Donruss brand. The cards were given the Leaf logo to differentiate the products, which also featured bilingual text and smaller, more curated 264-card checklists featuring a heavier emphasis on Canadian teams. These cards were produced annually from 1985-1988, though their popularity began to sag in the latter part of this run with 1987 and 1988 cards appearing in much lower quantities than earlier iterations. Popular price guides like Beckett initially carried monthly updates for fluctuating values of Leaf cards, but by the first pitch of the 1987 All-Star Game had dropped the cards from their pages. Baseball cards were more popular than ever, and even then collectors couldn’t be bothered with the brand. Clearly, Leaf needed to do something better with its IP than chase kids’ Canadian quarters.

While Donruss’ product development team tried to figure out what to do with Leaf in 1989, they watched Topps bring the Bowman brand back to life with its first cards since 1955. The resurrected cards clearly sought to tie their lineage back to the most visually appreciated set from Bowman’s past with a design based off the popular 1953 Color set. The callback to ’53 was further enhanced by making the cards the same size as the large format cards from a couple generations ago. The large size proved problematic for hobby acceptance, as modern collectors had largely configured their storage options to the standardized dimensions of cards produced after 1956.

Any decent marketing exec knows nostalgia can exert a pull on collector wallets. Any marketing team worth their weight also knows not to dilute higher tier products with lower tier ones. Using the Leaf brand to market Canadian versions of lower tier Donruss products wasn’t a winning strategy, particularly with Upper Deck’s debut product sending Donruss further down collectors’ shopping lists.

Donruss thought long and hard about this challenge as they watched hobby shops turn more and more of their spending towards Upper Deck. They designed their own premium offering to go head to head and by June 1990 they were ready to go to market. The cards, marketed under the Leaf banner, would be positioned as pedigreed competitor to Upper Deck and as an anti-Bowman example of how to successfully reintroduce a hobby legend.

The first card in the set clearly laid out what Donruss was hoping to achieve. It didn’t feature a minor league prospect, like ’89 Upper Deck’s Ken Griffey, Jr., or a subset like Record Breakers or Diamond Kings. The front of Card #1 featured little more than the Leaf logo. The back gave a sales pitch that hit all the high points while letting the ghosts of the ’49 edition whisper to collectors that they should hold onto these marvels. The text starts out with legendary names from the 1940s checklist while reminding collectors that Leaf was the first to put them in modern color. In a hobby first, a baseball card specifically mentions a price guide, ensuring readers would draw their own conclusions about how valuable their new cards could become. While it had been danced around many times before, this may have been the moment when hobby producers began to overtly tie baseball cards to monetary value. The mention of Leaf cards being on display in the Hall of Fame reinforces this concept and is a dig at newcomers that do not yet have the hobby gravitas to be considered museum pieces.

The text concludes with other important datapoints meant to raise the desirability of the cards. It explicitly states the cards are direct descendants of the ’49 set. Like the earlier cards, these would be issued in two separately packaged series for collectors to chase. Left to the imagination was the possibility that, like their 1949 counterparts, one of the series could be produced in smaller quantities. Not left to the imagination and stated in no confusing terms was the fact that the small checklist (264 cards per series) would feature only “dominant players and prominent rookies.” This meant collectors opening packs would find a greater proportion of names they actually wanted instead of the deep roster filler material found in Upper Deck’s massive 800-name monster. The hobby would get what it wanted, superstars and rookies, and would get them with superior production quality. Leaf was hoping to relegate Upper Deck, with its bloated checklist and newcomer status, as nothing more than a well-dressed pretender to the hobby throne.

Upper Deck and the Anti-Bowman Sosa Card

For all the protestations that Leaf was the rightful heir to a cardboard throne, the brand put quite a bit of effort into emulating what had made Upper Deck so successful. Packs of the new and improved Leaf hit shelves not in Donruss’ familiar wax packs, but in shiny metallic wrappers reminiscient of Upper Deck’s tamper resistant packaging. The cards themselves instantly brought to mind Upper Deck’s white-bordered aesthetic. Team logos are positioned in exactly the same spot as those in the Upper Deck offering. The brilliance of Leaf’s white border is enhanced by premium cardstock and by almost metallic silver accent stripes emanating from the logo in the lower left corner.

The back continued this metallic theme and introduced an element from another popular upstart brand; Score. In addition to the standard statistical tables, many cards had biographical paragraphs about their subject. Sosa’s bio is interesting for two reasons. Unlike anything else on the market, the text is so up to date that it mentions his winning a starting role in the White Sox outfield during the current year’s Spring Training. It goes on to identify him as the primary target of Chicago’s trade of Hall of Famer Harold Baines to the Texas Rangers.

As was the case with Upper Deck, photography was a big deal for Leaf. Upper Deck had shown the success of marrying premium card stock with high quality aqueous color transfer. Leaf did exactly that. Again, looking to recent well received newcomers Upper Deck and Score, Leaf utilized a two image format for its cards. Action shots were used on the front of every card and were balanced by tightly cropped portraits on the reverse.

Unlike Upper Deck’s use of photographs taken across the previous season, Leaf’ made an effort to capture the most recent likenesses of its subjects. Leaf’s mid-summer release date allowed it to capture images from Spring Training and early season MLB games. Sosa, like many of the newest Chicago arrivals, is depicted in a road uniform playing an April 1, 1990 exhibition game against the Texas Rangers.

In searching for the source of the image used on the Sosa card I came across a series of photographs from the same game. The were taken by Sports Illustrated photographer Chuck Solomon but were taken from the opposite side of the field (Right handed batters are seen from behind and the Rangers’ dugout is seen in the background of most shots). Labels affixed to the images state they were taken April 1 at Comiskey Park, though this location appears dubious given the presence of road uniforms and the fact that the Sox were in Florida at the time. Given the presence of the Rangers, whom Chicago played that day, it appears the error lies in the location rather than the date. Importantly, the Sox players depicted in road uniforms in the Leaf set were all present for that particular game, something that cannot be said for images outside of that a particularly dense Spring Training schedule.

Solomon wasn’t the man behind the lens for the Sosa card, but he was present for that game and captured Sosa and company in the same uniform, arm band, and eye black combinations as they appear on their baseball cards. Fortunately, a search for Donruss-affiliated photographers turned up the name of Jack Wallen. He was the company’s go-to photographer for many of their baseball cards, particularly when it came to capturing images from East Coast Spring Training. Many of Wallen’s negatives that had made it onto Donruss/Leaf products were sold off in team-specific lots by Lelands in 2006. They are marked with his name, the date the image was captured, the identity of the player, and the names of the teams involved in a game. While I have not found the exact image within examples from this collection, I would bet it resides somewhere in that lot.

The April 1 game took place in Charlotte County Stadium in Port Charlotte, Florida. A distinct yellow border existed above the dugouts and can clearly be seen in the ’90 Leaf card of Frank Thomas (who had not yet played at the famously yellow-railed Comiskey Park). Charlotte was the home of the Class A Advanced Charlotte Rangers, with the parent organization using the ballpark for Spring Training from 1986-2002. The Rangers connection is strong, with Sosa having played there as a minor leaguer in 1988 and Nolan Ryan announcing his retirement from the clubhouse a few years later. The stadium, constructed in 1987, was later used by the Tampa Bay Rays for Spring Training until it was severely damaged by Hurricane Ian in 2022. It is now known as Charlotte Sports Park.

Sosa, the man who would eventually eclipse the 60-HR mark on three occasions, is depicted ready to bunt. Although the Rangers would win the game by a score of 3-2, Sosa held his own in right field and drove in Lance Johnson in a 1-3 performance at the plate.

The fact that there was even a Spring Training at all was a minor miracle. The 1990 practices and Grapefruit League games were condensed into a condensed schedule due to a lockout of players by team owners. This action had followed quickly on the heels of the breaking of owners’ collusive practices on player compensation, specifically an October 1989 arbitration ruling against the owners. A tentative peace was secured in time to allow the 1990 season to proceed, but the storm clouds that would eventually lead to the 1994-95 strike were gathering.

Hobby Reception

Leaf’s efforts towards a brand reputation glow-up were rewarded. Series 1 cards, which included Sosa, arrived on nationwide dealer shelves and select West Coast and Michigan retailers in July. They were an instant hit, aided by a fairly extensive print advertising campaign in the months ahead of their launch. The ads touted the cards as “destined to become a collecting phenomenon” and reiterated the connection to Leaf’s set from 40 years earlier. The ads specifically called out the numerous stars, prominent rookies (no scrubs) and, harkening back to Sosa and other Spring Training photos, players involved in “major trades” would be shown with the correct teams. Cards were “printed on superior stock with state-of-the-art technology” and were said to offer collectors the opportunity to build “the set of a lifetime.” No Donruss logos were to be found. The campaign concluded with the tagline “The Card of Connoisseurs,” showing that cards based on a clinical white bordered photograph could still be anything but subtle.

The cards were well received, but experienced a bit of a slow burn towards the top of the 1990 collecting landscape. Reporting to the Beckett Hot List at the end of 1990, collectors placed a pair of that year’s card issues at the top of their want lists: Upper Deck and Score. The next year, the same brands saw their 1991 editions again make the Hot List without any reference to Leaf. Then, in May, survey respondents elbowed ’90 Leaf into its first appearance on the Hot List, the first time a specific set from outside of the current year managed to do so. By December the set was still climbing the charts and was the only set shown within the rankings.

Other measures of popularity were telling a similar story. Selling at a premium price of $1/pack at their debut, the cards had initially appeared in price guides at an elevated level. Full sets were changing hands in December 1990 at roughly double the price of the Upper Deck competition. It was the latter half of 1991 when the set truly saw its popularity blossom. Full sets were now reported at $275 against just $37 for Upper Deck. What precipitated turning the slow burn into the economic equivalent of a space shuttle launch?

Collecting through the mid-1980s primarily consisted of building each of the major sets put out by Topps, Donruss, and Fleer. The introduction of Score and Upper Deck in the latter half of the decade gave collectors pause as they struggled to find space for their ever increasing number of boxes and binders. Many of these formerly maximalist collectors began to refocus their efforts on building just a single set to represent a season. Throughout 1990 this took the form of a race between Score and Upper Deck, which had their products out to hobbyists by Opening Day. Issued later in the year, Leaf cards grew on collectors to the point where they began to consider it the definitive card product of the year. Something that achieves that status simply has to be in a modern collection.

And what was the driving force that pushed Leaf ahead of Upper Deck? Rookies. Upper Deck put itself on the map by leading off its 1989 effort with the most iconic Ken Griffey, Jr. card of all time. Their sophomore effort contained plenty of relevant rookie talent, though there were some glaring holes. National League Rookie of the Year David Justice and Cleveland infielder Carlos Baerga didn’t appear in packs of Upper Deck until the season end high series was released. Importantly, Frank Thomas was a complete no-show in the UD checklist. All of these were in the ’90 Leaf offering.

As 1991 unfolded, Thomas became one of the biggest names in hobby. A set that didn’t feature him could never be the centerpiece of a collector’s representation of 1990. Leaf’s most direct competitor was effectively disqualified from hobby consideration with that glaring omission. As Thomas’ massive stature grew, so did the demand for the set containing his definitive rookie card.

From that point forward, 1990 Leaf became the defining rookie card of anyone making their cardboard debut in the set. Sosa is no different, with collectors having to make clarifying remarks if the Sosa rookie they describe in their collection is anything but the one produced by Leaf. An example of this can be seen with Sosa’s cardboard. He made a single baseball card appearance in 1989, seemingly making his ’89 Donruss Baseball’s Best the focal point of anyone seeking a rookie. Instead, collectors find themselves quickly flipping past this green bordered card for the high tech follow-up from Leaf.

Production and Distribution

As far as Junk Wax Era cards go, those from ’90 Leaf aren’t exactly printed to the moon. The general consensus in the hobby is that 1-2 million of each card were produced, a figure on par with what is known about 1989 Upper Deck and Topps’ production within the 1984-85 timeframe (and the 1.1 million or so Topps put out in 2023). I guess that’s what restraint looks like in a hobby boom.

No factory sets were issued by Leaf. Cards were only sold via 15-card packs. These were distributed to hobby outlets in 36-count foil boxes packed 10 per dealer case. The number of boxes per case was exactly half of the 20-count volume typically shipped for Donruss’ flagship offerings and, given the doubling in suggested retail price, was likely a conscious decision to keep the cost per case unchanged from retailers’ past experience.

Collectors purchasing cards could find Sosa only within Series One packs. Assuming no duplicates within any randomly selected pack, at least one Sosa card could be expected to be found at the following rates:

| Package Format | Cards Inside | Odds of Finding Sosa |

|---|---|---|

| Single Pack | 15 | 5.7% |

| Full Box | 540 | 87.8% |

| Full Case | 5,400 | 100.0% |

The small checklist provides relatively high odds of pulling a Sosa rookie from any chosen pack of cards. The one caveat to this is Leaf’s problematic collation method. Anyone opening a box of these cards will quickly note repetitive sequences of cards. Due to this, completing a full set is highly unlikely from any given box of cards. Finding one Sosa indicates rising odds of locating another copy in the same box while the lack of a Sosa in a pack starts to weigh against finding one at all.

Counterfeits

Not every 1990 Leaf Sosa card was officially sanctioned. Some came from your local print shop. A massive forgery ring was taken down by the FBI around 25 years ago under the now famous name “Operation Bullpen.” Several smaller investigations were spun off from the primary focus on fake autographs, one of which involved a printing shop in a Los Angeles suburb. There, counterfeiters produced large quantities of fake 1985 Topps Mark McGwire, 1983 Topps Tony Gwynn, 1984 Topps Dan Marino, and 1984 Topps John Elway rookies. From there, conspirators would take the cards to shows in San Francisco and Miami to be quickly sold in bulk to dealers before being ultimately passed on to unsuspecting collectors. The number of counterfeits known to have escaped into the wild is north of 20,000.

After documenting the operation, a sting was set up to capture those involved. Investigators learned of their latest target, the 1990 Leaf Sammy Sosa, and placed orders. Large numbers of Sosa cards were produced, and combined with leftover stock from faking the earlier cards, led to more than 50,000 counterfeits being seized when the print shop was raided. Reports of the seizure state that none of these Sosas were distributed. The counterfeiting investigation led to six guilty pleas.

Operation Bullpen took nine years to fully play out, a period that saw substantial numbers of dubious items enter the collecting hobby. The Sosa cards were just one part of this dishonesty, itself just one of multiple sources of counterfeit cards entering the hobby. Additional fake 1990 Leaf cards, primarily those of Frank Thomas, have been discovered floating through collections over the past 30 years. Collectors need to pay close attention to the cropping of player images, color quality, and especially the printing patterns seen in the silver stripes on the front at high magnification.

Trading For a Sosa Card

Although baseball cards had been seen as having monetary value for more than a decade, Leaf’s advertising broke the manufacturer taboo by explicitly highlight the market prices for its most famous set. By the time it did so, the idea that these bits of cardboard were potentially valuable was already part of the hobby and quite possibly its driving force. I don’t recall to what extent I knew this as a 9-year-old buying his first pack of ’91 Donruss, though I am certain I was aware that there was more than pocket change involved in the hobby.

Everyone on my Little League team and at school could sense it. We still enjoyed the old school aspect of baseball cards. We routinely fed our commons to bike spokes, but only after consulting ubiquitous price guides to make sure sacrificing a 1991 Fleer Randy Veres or 1989 Donruss Todd Frohwirth wouldn’t jeopardize anyone’s retirement plans.

A big part of our card related activity was making trades. Everyone had an idea of what cards they were after, but any transaction had to abide by one unchanging rule: Equal value must be received for anything traded away. The sum total of all cards being received must exactly equal the total value of whatever was being given up. Trading baseball cards was often a team sport, with multiple parties rummaging through price guides and binders to propose ways to even out the financial value of any proposed deal.

Beckett provided prices every month, and whoever got ahold of each new edition generally had the ability to initiate trades ahead of the others. What would it take for a young collector sharing my lunch table to obtain a 1990 Leaf Sammy Sosa card? Using the average value of the high and low columns of year end Beckett guides, an all too familiar story arc emerges for the rise and fall of demand for the most recognizable card in anyone’s Sammy Sosa collection.

The first pricing data for ’90 Leaf cards appeared in October price guides. By December we knew that a card from an upper tier set would be needed to secure anything from the hobby’s newest manufacturer. Sosa was seen as a promising rookie, as were names like Hal Morris and Eric Anthony, both of which had similarly ranked cards in the 1990 Upper Deck set. Greg Maddux seemed to be emerging as the best pitcher on the Cubs, though that came with the caveat that he pitched for the Cubs. Still, 1987 Fleer Update wasn’t something to sneeze at. Any of these cards would have been fair game.

By 1995 Sosa had established himself as a solid player, certainly better than being just one of the highly touted prospects that briefly capture the attention of the hobby. That put him in the same conversation as fellow 1990 rookies (speaking in baseball card timelines) Marquis Grissom and Carlos Baerga, all of which were known for speed on the basepaths with hints of modest power. Grissom and Sosa Leaf rookies were considered interchangeable in terms of value and collectors would be happy walking away from a deal with either one tucked into their binder.

Premium brands and inserts were the focus of the collectors still active after the strike. Donruss’ Leaf still occupied that “better than base” market segment in 1995 but had graduated beyond the simple formula of nice photos printed on quality materials. Packs of ’95 Leaf featured 10 different insert sets for collectors to chase, and buyers of retail (not hobby) packages could expect to pull any one of nine .300 Club inserts at a rate of 1 every 12 packs. These cards were anything but scarce, but collectors of the era valued them much more dearly than the base cards bearing similar overall production runs. Choosing between Sosa’s best rookie and a middling insert of a second baseman was a tough decision back then.

Sosa left Grissom and Baerga in the dust when he launched 66 home runs in 1998. Well known hobby brands had stepped up their game as well, with upper tier brands like Leaf and Upper Deck no longer cutting it. Ultra Premium brands were now required to capture eyeballs. Topps had introduced Finest in 1993 and Chrome in 1996. The much maligned Bowman had cleaned up its act in 1992 and by 1995 was producing a chromium line of cards under the name Bowman’s Best (leaving one to wonder what flagship Bowman should be called – the leftovers?). Leaf was now producing even shinier cards under the Leaf Limited flag. Upper Deck brought out SP to compete with Finest in 1993 and went a step further with SPx in 1996. Pinnacle added its short-lived Zenith brand to mix. I would name more but by this point the print in my old price guides was getting too small.

Not only were more brands than ever popping up, they were showing up in multiple formats. By 1998 parallels had replaced inserts as the primary focus of modern collectors. Topps Chrome/Bowmans Best/Finest all had Refractors, Leaf had 7 different Fractal versions of each of its cards, SPx had two parallels, and Zenith had a couple gold themed versions floating around. Somehow, against this backdrop, the earlier parallels of 1994-1995 seemed almost normal.

Sammy Sosa, Scott Rolen, and Alex Rodriguez combined to hit 139 home runs in 1998, 33 more than Sosa’s 1990 White Sox and a dozen more than the Bash Brother-fueled champion 1989 Athletics. Rookie card parallels from premium brands where at the top of collector want lists and it would take giving up the rookie of a guy who just clobbered Roger Maris’ mark to get one of Rolen or A-Rod.

This was the point in the timeline where Sosa’s rookie topped out in terms of demand. Rising interest in third party grading, primarily through BGS, saw Gem Mint examples of the ’90 Leaf top out at $1,200 a piece the following year. Grading ended up taking the hobby by storm and today there are 39,589 examples of the Sosa card in slabs, nearly 3,000 of which carry Gem Mint designations. The card is the 26th most graded baseball card of all time.

Three years later the novelty of hitting 60 home runs had worn off. Despite eclipsing the 60 mark twice in two years, Sosa rookies had given up more than half their value. That’s the effect one sees when Barry Bonds buys some new hats and hits 73 dingers. Still, this was good enough to get a classic card of a Hall of Famer, like a ’61 Topps Carl Yastrzemski. Premium parallel rookies were still in demand and although he had just 21 HRs to his name by the end of the season, Alfonso Soriano was gaining quite a following with the Yankees (he would go on to become the fourth member of baseball’s 40/40 club).

Things were different in 2005. Perhaps it was seeing Sosa testify alongside Mark McGwire and Rafael Palmeiro at congressional hearings. Maybe it was the hobby (temporarily) pulling back from parallels to chase meaningless “relic” cards. Whatever the reason, Leaf rookie cards of the still active Sammy Sosa could be traded straight up for base rookies of a new crop of stars. Albert Pujols had begun his assault on 700 home runs and collectors were seeing his Topps Traded rookie as equivalent to Sosa’s. He would surpass Sosa’s 606 career HRs in 2017. Carlos Beltran, himself a potential Cooperstown resident, lends his name to a rookie card that could also nab a collector a Sosa rookie. The term “lends his name” is used purposely, as Topps mistakenly pictured rhyming Royals prospect Juan LeBron.

Sosa retired in 2008 and the hobby came full circle. Many of the junk wax eras brightest stars saw collector interest in their cards compress to around the same levels. Sosa’s Leaf rookie, now down more than 90% from its peak, was seen as equivalent to that of Frank Thomas. That particular Thomas card had once rivaled the ’89 Upper Deck Ken Griffey, Jr. for hobby supremacy and doomed Upper Deck’s follow-on offering by its omission from the checklist. Roger Clemens’ ’85 Topps rookie, already a classic for more than 25 years, was likewise seen as perfectly interchangeable for a Sosa or Thomas rookie.

And what now? Back in 1990 nobody would have predicted that by the end of the decade the number of homeruns hit in Major League ballparks would double and Sammy Sosa would repeatedly record numbers starting with a six. Back then nobody thought the game’s biggest stars would end up testifying under oath about their nutrition regimens. Near economic collapse in 2008 and a worldwide pandemic in 2020 were far from most people’s minds. I didn’t think I would ever stop collecting baseball cards, yet a 20 year gap exists within this timeline.

The ’90 Leaf Sosa is back to being the second most sought after name in the checklist, slightly behind Frank Thomas and on par with Ken Griffey, Jr. The Junior card itself was once the second most sought after Griffey, behind the ’89 Upper Deck and briefly commanding prices north of $30 in the early 1990s. Another player with Griffey-level popularity, Derek Jeter, can be seen wearing a borrowed Yankees jersey at a Michigan high school field on his second best Upper Deck rookie. These are all popular cards, though they are almost always available raw at any price point between $1-$5 at any show or online marketplace you frequent.

Sosa himself finished second in home runs every time he hit more than 60, finishing behind Mark McGwire (twice) and Barry Bonds. Aside from that success in 1990, Leaf never really eclipsed Upper Deck. As a mass produced card now seemingly doomed to reside in $1-$5 discount bins far away from Cooperstown, it would appear the card’s story, and hobby impact, are about over.

This belies one compelling fact: 1990 Leaf, and the Sosa card that largely defines the set in the eyes of many baseball fans, had a far larger impact on modern baseball cards than just an incremental step up in quality. We began this look at the card by discussing the trend towards bigness in everything. While that largesse blew up Sosa’s numbers and baseball in the late 1990s, it led to a counter revolution in baseball card collecting. Leaf consciously pivoted its checklist away from the 800-900 count sets of the early 1990s towards a more curated checklist. The ability for a collector to buy a pack of cards and actually get the players they wanted was game changing. The hobby has seen a steady, multi-decade march towards smaller flagship checklists and relegated the “get everybody on a card” mentality to prospect oriented sets. This card, and a small number like it, changed the course of the hobby. Probably for the better.