Those who are familiar with my collecting habits are aware that I carry a few baseball cards with me wherever I go. The cards are chosen with a theme in mind and I tend to populate these selections with cards that would have amazed the 10-year-old version of myself. I keep them in my pocket, tucked into a wallet with no other form of protection around them. This results in the accumulation of a good deal of cardboard damage with the cards that emerge looking very much like the worn out beaters inhabiting a satisfying vintage card show discount bin. These are what I refer to as my “wallet cards.”

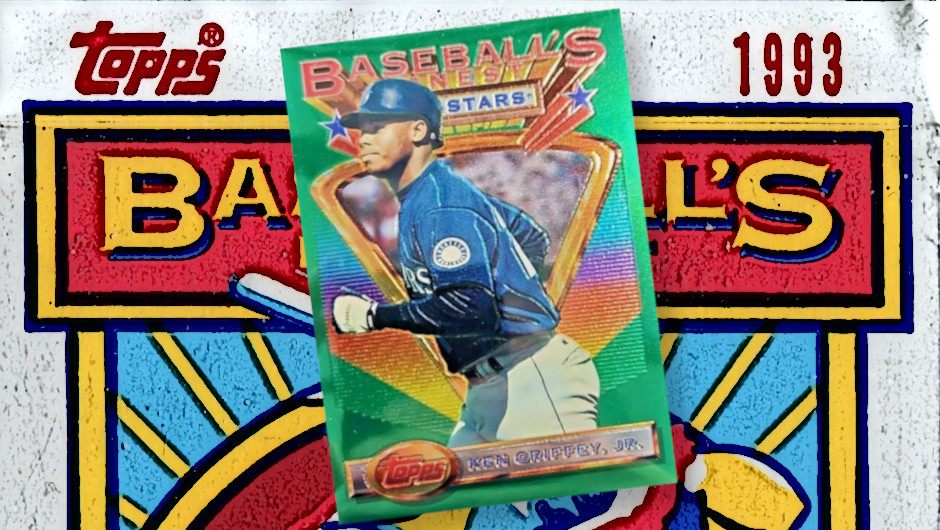

Each wallet card spends exactly one year traveling with me before being placed incongruously into a protective holder. Twelve months is a good amount of time to get to know a piece of cardboard and I rather enjoy following all the rabbit holes and story lines one can generate. Last year I carried three Ken Griffey, Jr. cards with me. One of these was his All-Star card from the 1993 Topps Finest set, an issue of intense interest to me given a step-change towards lower print runs and an irrevocable leap towards the modern incarnation of a century-old hobby.

The hobby had been experimenting with higher quality cards after Upper Deck debuted its wares in 1989. Small steps towards the future could be seen with the introduction of glossy photo-centric cards from Stadium Club and Studio, foil heavy parallels from Leaf and Topps, and inserts limited to a then-unheard of print run of 10,000 copies. It was expected that future years would see incremental improvements, perhaps with slightly harder to find inserts, a bit more shiny foil, or maybe even an experiment or two with higher quality cardstock.

Then, without warning, Topps nuked the competition and our idea of what a baseball card could be. Midway through the 1993 season the card manufacturer issued press releases announcing a new set would be released into the hobby. Landing amid the summer’s National Card Collecting Convention, the set’s release was timed for maximum impact. It did.

For starters, this card looked like nothing else previously seen by collectors. The card was shiny, appearing almost metallic under an ultra deep gloss coat. It looked less like having been printed on cardboard and more like artwork painted onto a custom motorcycle or sports car. Almost every premium set issued today can trace its lineage back to the introduction of these cards and their “chrome” printing technique.

The new look was possible because the card was constructed unlike anything previously released. Earlier products had been created with various layers of cardstock, augmented by the odd bit of foil either embedded in one of these layers or, more often, stamped onto the surface. Traditional materials were only a starting point for this card. Bright white cardstock provided the foundation of the card’s skeleton, but was covered on one side by a layer of reflective foilboard. Ultrathin plastic films were then applied, some with embossed versions of the underlying printed design. The resulting card had the effect of depth and three dimensional mass, coupled with the visual effects of light playing off the foil and traveling through the varying angles of plastic.

Aside from the heavily embellished borders, cards focused on closely cropped action shots. Blurred ballpark backdrops are visible in limited areas behind each player, though these are not part of the primary image and are actually a series of a half dozen generic pictures that rotate throughout the checklist. The All-Star subset, of which this card hails, all use the same background image inside an inverted triangle.

With card manufacturers’ flagship releases hitting store shelves in January or even earlier, Topps wanted to make its new product stand out by featuring players in new uniforms. Current Spring Training photography was used whenever possible in order to capture players with new teams or, in the case of the Mariners, in newly designed uniforms. Griffey is shown midstride in Seattle’s new blue/silver/teal uniform, a color scheme first revealed to the public in February of that year.

Like all Mariners, he is depicted on the front of his card in a road uniform. Making this possible is the fact that the team did not have a home field for that year’s Spring Training games, having just moved from Tempe to a new facility in Peoria that had yet to get a working ballfield. The same look appears on multiple Griffey cards from that year’s releases of Topps Stadium Club. Coupled with the fact that Griffey appears to have worn eye black in many of his 1993 Cactus League games (captured on the back of the card), it would appear the Stadium Club and primary Finest image were taken at the same game. The most likely photographer to capture this would be Doug McWilliams, a longtime Topps photographer who was making his final Spring Training trip on behalf of the company.

Production and Distribution

Collectors had long required market research and plenty of guesswork to determine which cards qualified as being “rare.” A few manufacturers, such as Classic and Star, would sometimes tell the hobby how many sets were produced though these were seen as second-tier issuers. Publication of their print runs seemed to only confirm they were overproduced. Mainstream issuers like Upper Deck would hint at their production only to later draw criticism for allegedly keeping the presses going. Upper Deck did introduce serial numbered cards in 1990 with its autograph inserts, prompting Donruss to debut its own inserts numbered to 10,000 the following year. These cards were major chase issues of the time and were synonymous with scarcity.

That’s when Topps broke everyone’s mind. Coinciding with the 1993 National Card Collectors Convention, the firm announced the release of its new line of premium cards. Drawing particular attention was a statement that only 4,000 cases of the product would be produced. Working from this figure, collectors quickly deduced that there were 48,000 boxes that each contained 108 cards. Dividing the resulting 5.2 million cards leaving Topps’ facilities implied a print run of 26,050 of each card, a number that would be further reduced by several hundred after accounting for parallel versions of each player. Cards were only made available in traditional pack form with no factory sets or jumbo packaging varieties put into use.

Getting ahold of a pack to open proved challenging as limited production was met with limited distribution. Some of the highest volume hobby outlets had standing orders to purchase cases of whatever Topps released. Such orders received first priority in fulfillment, leaving only a small remainder for dealers who ordered on a product by product basis. The result was few shops receiving shipments and a scramble to secure cards on the secondary market.

Assuming a collector did manage to obtain a pack or box, what were the odds of getting the Griffey card? Finest packs exhibit a pattern in the way the cards inside are collated, resulting in odds that are not totally random. An upcoming post on the intricacies of Finest packaging will include full details of the collation process.

| Packaging Format | Cards Inside | Odds of Griffey |

|---|---|---|

| Foil Box | 108 | 42.2% |

| Foil Pack | 6* | 3.0% |

*Note: Packs were intended to contain 6 cards. A small number appear to have 7 as a result of cards sticking together in the packaging process. When this occurs the cards always appear next to each other in numerical order (e.g. the card sticking to #35 will always be #36, #151 will be followed by #152, etc.). The above odds assume only 6 cards per pack as this appears to be a rather limited occurrence.

Similar Cards

This particular Griffey card is available to collectors in two additional varieties.

Packaged atop the packs in each box of 1993 Finest was a single jumbo version of one of the checklist’s 33 All-Stars. Measuring 4×6″, these box toppers were a bit unwieldy and received a mixed reaction from collectors. The 1 per box insertion ratio presents those that remain interested with a sneaky low print run to chase. With 33 names to choose from and 4,000 cases having been produced, the implication is that less than 1,500 of the Griffey jumbo exist. This results in one of the rarest early-’90s Griffey cards, beating out widely sought issues like 1991 Topps Desert Shield.

Of course, this leads to the real reason why collectors focused on scarcity generally look past a genuinely tough card: There is another version printed in even smaller quantities. The most memorable part of the 1993 Finest issue is the introduction of Refractor parallels to the hobby. Only a few hundred of each card exist and the ultra-colorful Griffey was among the most popular from the day it was inserted into packs.

Grading

1,292 of the base Griffey have been graded by PSA, with those receiving a numerical grade ranging from a trio of VG-EX 4s to 115 Gem Mint 10s. Add in the additional 142, 177, and 28 assessed respectively by SGC, Beckett, and CGC one can see that a pretty good sampling of the total print run of these semi-plastic cards have been encased in more plastic. Approximately 1 of every 16 of this card has been slabbed, a ratio not too far from Griffey’s famous 1989 Upper Deck rookie.

Trade Night

As kids, my friends and I would often trade cards to nudge our collections closer to our individual ideal states. If we weren’t direct participants in a trade, we were sticking our noses into someone else’s deal. Almost every trade in my neighborhood seemed to have an audience, and those extra eyes would immediately find a voice if they felt a trade did not represent equal value for all parties in the transaction. To adjudicate these situations, we always referenced the latest price guide and balanced the scale with extra cards on whichever side of the trade was coming up short. Need $0.30? Toss in a half dozen commons from the other guy’s favorite team. Need $3.00? Better get your “good cards binder” out.

These trade values were always relative. In hindsight what were once evenly matched trades could drift into examples of apparent steals. On field performance could send demand for a particular card up or down. The ever present phenomenon of collectors clamoring for the latest release also led to initially high demand for new sets followed a couple years later by a drop in collector interest. The interesting part of this is how what would be offered for a particular card changes through time.

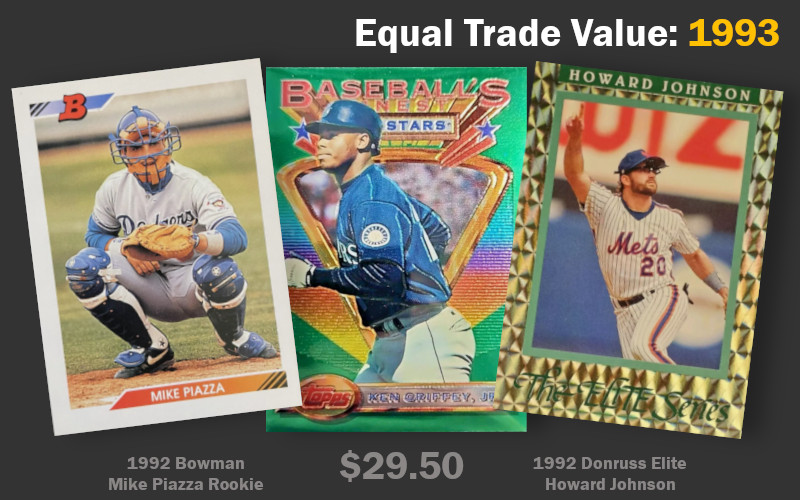

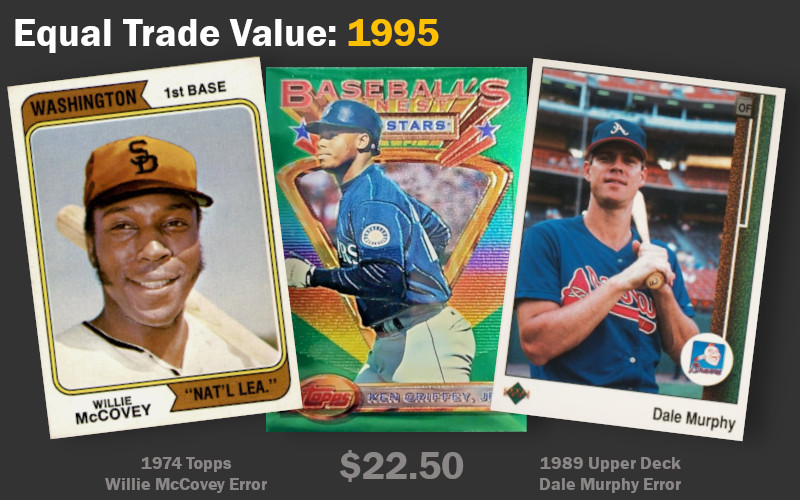

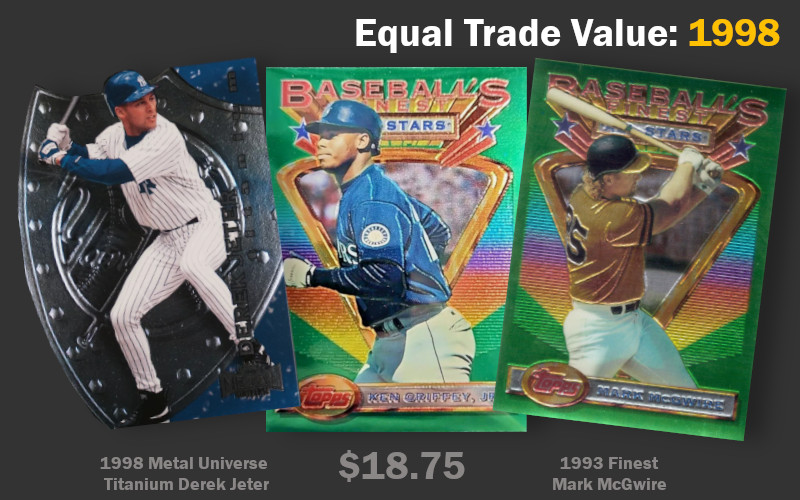

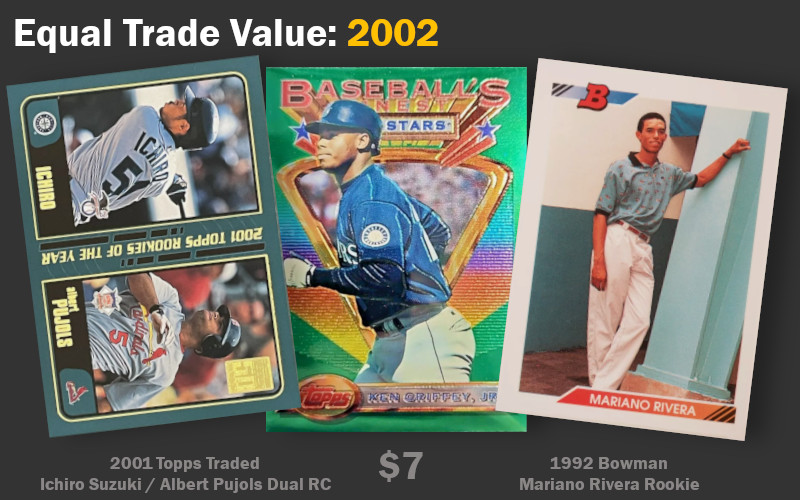

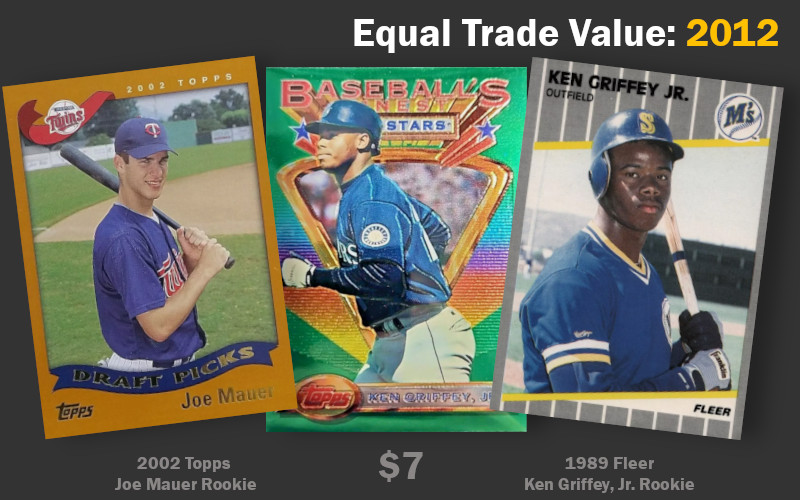

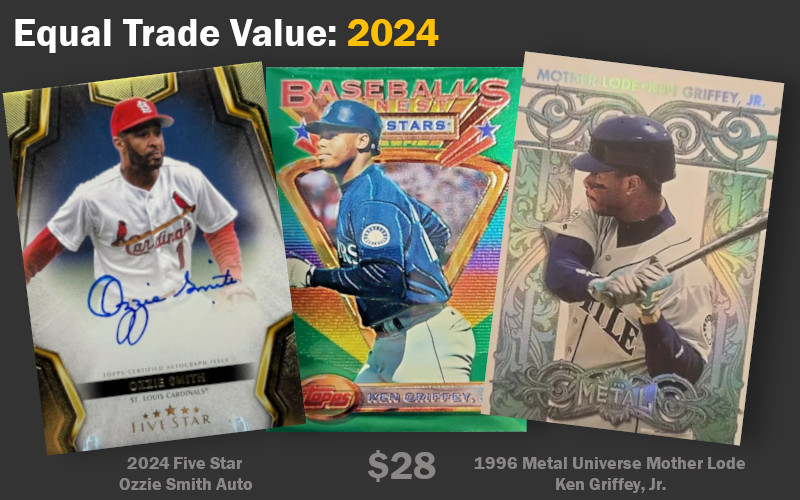

What follows is a look back at my stack of old Beckett Baseball Card Monthly price guides. I looked up the reported value of the Griffey card at the end of each year, averaging the low (card show price) and high column (full retail in a card shop) values to come up with an approximate trade value. The process was repeated to find interesting items that could have produced happy collectors on both sides of a trade in those years.

This exercise started off as a purely theoretical one. There was never a trade involving a ’93 Finest card between my friends. We simply never had any. The cards were printed in much lower quantities than anything else we had seen and were never on offer at the stores we frequented. A few started to appear at local hotel and mall shows, but by the time this happened pack prices were already well into double digits and anyone purchasing singles wasn’t putting them out for trade.

Finest wasn’t the only product that seemed to only exist in myths and legends. None of us had any of the Donruss Elite cards, inserts that were limited to “just” 10,000 copies each of 10 different players. There weren’t any commons among the Elite checklist, though there were a few names that one could envision trading away for one of the newly issued Griffey Finest cards.

A single box of 1992 Bowman made it into my neighborhood, carried as part of the inventory of a local movie rental shop with a manager who also aspired to be a card dealer. The surprise success of the set caught everyone off guard and the movie guy quickly raised his price to $5/pack. A portion of the box had already gotten “into the wild” and some of the more entrepreneurial kids with lawn care businesses continued to pick off the odd pack here and there. By 1993 the Bowman set had found its key card in the form of Mike Piazza’s rookie. If there was going to be a 1990s equivalent to an ’84 Donruss Mattingly or ’86 Canseco, this was it. It would have taken one of those never-seen Elite cards or one of the top cards in the Finest to pry away a ’92 Bowman Piazza.

Fast forward a few years. By this point I had at least seen some ’93 Finest cards in dealer cases, but none had yet entered the collections of my friends. At age 13 there were fewer of us still trading, but those that remained active were much more savvy. We could identify any postwar set on sight and knew what to look for when it came to error cards. Collector interest in errors and variations was fading a bit, having peaked in popularity in the late 1980s, but they had been front and center in the price guides during the most formative collecting years of my age group.

A trade sometime around this period led to the acquisition of a 1974 Topps Nate Colbert error for my collection. His San Diego Padres were considering an east coast move to replace the recently departed (again) Washington Senators. In anticipation of such a relocation, Topps began 1974 by depicting its San Diego names as playing for “Washington Nat’l Lea.” Colbert was an excellent power hitter, but Willie McCovey was the big name among the cards that were only so briefly printed with the Washington designation. That particular card would remain as out of reach as a ’93 Finest Griffey.

Equally out of reach was the much more famous Dale Murphy error with a reversed image from 1989 Upper Deck. One Braves-obsessed friend who lived on a cul-de-sac a block further down the street had obtained a copy that I was occasionally allowed to look at. At one point he tried to charge younger kids admission to see the card, but to them ’89 Upper Deck was this thing that had always existed and therefore did not hold the same mystique it did for us. Where were you when you first shook your head and muttered kids these days?

I got my driver’s license in the early days of 1998. Taking my first solo drive, I made my way to a drive-in lunch spot a few blocks away. My second solo drive was a return trip home, as I had forgotten my wallet and needed to retrieve it in order to pay for my rapidly cooling food. This provided ample opportunity to listen to radio discussions about Spring Training.

Griffey had come tantalizingly close to Roger Maris’ single season homerun record in 1997, as did Mark McGwire. Although it was only pitchers and catchers reporting at such an early stage of the calendar, all talk was about the possibility that Griffey or McGwire could set a new record. While Big Mac was the more prodigious longball hitter, Griffey was seen as the more likely candidate given his ability to remain healthy. By the end of the year Griffey had tied his ’97 production with 56 HRs while McGwire blew past the record with 70. Griffey had been king of the cardboard world for several years at this point but 1998 saw McGwire’s cardboard rise to equal value for seemingly every non-1989 issue in which they both appeared.

1998 wasn’t just peak longball mania. The era of chrome cards that began with the release of ’93 Finest had evidently reached its zenith alongside the peak of the insert-crazed 1990s. Card manufacturers were not only releasing mind-numbing quantities of insert set titles, they were also multiplying the number of releases with increasingly tiered sister-sets to a multitude of already existing brands. Mergers were also rapidly bringing crossover products between previously rival brands. Fleer and Skybox had joined forces under corporate parent Marvel in 1995. Within 3 years they were right in the thick of it with an entire lineup of chrome-inspired cards. The Derek Jeter shown above is emblematic of this, carrying with it a shiny finish, die cut borders, and a challenging 1:96 insertion ratio. You could search and search for this card or, instead, hunt down a ’93 Finest Griffey or McGwire. It was your call and any choice would look like the right one.

The turn of the century brought with it shifts beyond those of the calendar. Griffey was no longer a Seattle Mariner, nor the player that had been so celebrated in the 1990s. Repeated injuries transformed his next decade of play into one in which he produced negative WAR in 5 of the following 10 seasons. Griffey’s cards were still chased, but not at any pace like what had transpired a few years earlier. This was a period where the next generation of stars saw their cards finally catch up and eclipse those of The Kid.

Leading the charge was Seattle’s newest face, Ichiro Suzuki. The Japanese and American League answer to Tony Gwynn, Ichiro captured Rookie of the Year honors in 2001. Joining him on the podium was Albert Pujols from the National League. By 2002 both had the hottest cards in the hobby. The pair were captured on a dual rookie card in the ’01 Topps Traded set and for a time the card was considered equivalent to the formerly top shelf Griffey from 1993. Mariano Rivera had also been carving up postseason batters for the Yankees every year since his debut in 1995 and would continue to do so for another decade. It took collectors a while to appreciate ‘Mo, but when they did his ’92 Bowman rookie began to see a surge in demand. This was the point at which the card finally caught up with the shiny Griffey.

While the ’93 Finest Griffey was still an in demand card a decade later, it was one that just didn’t see much action. Low print runs and the need to allocate increasingly scarce printing space led Beckett to stop reporting any base cards from the set for several years. Griffey himself bowed off the baseball stage in June 2010. The card would reemerge unchanged in price in Beckett when the magazine expanded its page count (but not font size) a couple years later. The enlarged price sheets reported the ’93 Finest could still command a decent trade: Collectors valued the Topps flagship rookie of Joe Mauer at the exact same level. Some nostalgia for the recently retired outfielder was also seeping in, with Griffey’s junk wax rookie cards rising in collector esteem to the same level as his Finest debut.

The market for Griffey cards wasn’t saying hobbyists were done with him, but rather that baseball cards in general were not at the forefront of anyone’s minds. The Global Financial Crisis was still fresh and nobody was in the mood to spend big bucks on cardboard. A survey of Heritage Auctions’ archives reveals the sale of a PSA 5 Leaf Jackie Robinson rookie for $1,100, multiple authentic 1933 Goudey Babe Ruths for $600, and complete sets of 1952 Bowman ($1,673), 1968 Topps ($837), and 1972 Topps ($448). Card prices had fallen for the better part of a decade and were bottoming out in this period. In this vein the ’93 Griffey holding the same value of a decade earlier seems almost an indicator of strong collector interest.

The introduction of the Topps Finest line three decades ago changed the way collectors interacted with their cards. Upper Deck had started the ball rolling in 1989, but it was the release of Finest that forced the hobby to skip ahead to an endgame of small set sizes, chrome finishes, and manufactured scarcity. Today you can still find willing trade partners who will gladly take a ’93 Finest card in exchange for something just as shiny. Browsing completed sales on eBay, I found the above cards all changing hands at equal prices. A numbered, pack-issued Ozzie Smith with an on-card autograph? An ultra-shiny Griffey insert from the popular Metal Universe line of cards? All are excellent choices and can trace part of their history back to this shiny green Griffey.

The Aftermath of Carrying This Card in My Wallet for a Year

This card certainly carries with it an element of hobby history and embodies a shift in how I collected. Griffey specifically came to epitomize perhaps the greatest decade of baseball card innovation, making the selection of this particular card well suited to serve as one of my wallet cards.

I have collected the shiny refractor versions of the ’93 Finest set for years and know first hand that the surface of these cards can be rather unforgiving. Imagine my surprise when this card emerged after a year in my pocket largely intact. I started with a copy in VG condition, an otherwise NrMt example that had a small crease on the back of the card. Over the next 12 months a few small bends appeared along the edges that never really developed into full fledged creases. The corners apparently could not decide if they would remain as right angles or become round with wear, a phenomenon I attribute to the embedded layers of plastic providing crucial support to the more fragile cardboard tiers. Even the ever fragile surface seemed to gather only a faint veneer of micro-scratches. An astute grader at PSA or SGC would certainly note the damaged surface, but the card doesn’t look terrible in hand. Certainly it does not bely having been unprotected as it was sat on repeatedly.

Overall the card looks much, much better than any of the other wallet cards in my collection. It is readily apparent that the mixed media approach to constructing a “better” baseball card helped create a more durable piece of cardboard. Yet, something is missing. The battle scars that were accumulated on this card are alien compared to the well-loved vintage cards I sought to emulate with this project. I enjoyed having this card with me, but based on this experience I do not recommend using a Finest card or any other plastic-infused chrome product as a wallet card. That is, of course, unless you want it to last.