My younger brother and I doubled our walking pace as we entered the rented ballroom hosting the local monthly card show. Dad had brought us to the now demolished Quality Inn for one of the half dozen local shows we attended each year. This was 1992 and we were 10 and 8 years old, and between the two of us we probably had $30 burning a hole in our pockets. My brother wanted wax packs and cards of Kirby Puckett and Nolan Ryan. I was searching for Jose Canseco and low grade vintage cards while Dad was on the hunt for his usual pack of top loaders that would be handed to us after we returned home.

My favorite vendor operated a three-table affair that was always located just to the left of the ballroom entrance. I do not recall what I picked up at his table that day, other than the cards I got were probably poor condition (not a complaint) and left me with exactly $10 in my hand. From this point my brother and I tag teamed the rows of tables, each taking one side of the aisle and calling out to the other if we found something worth looking at. This could be a time intensive process, as pretty much everything at a card show is worth inspecting when you are this age.

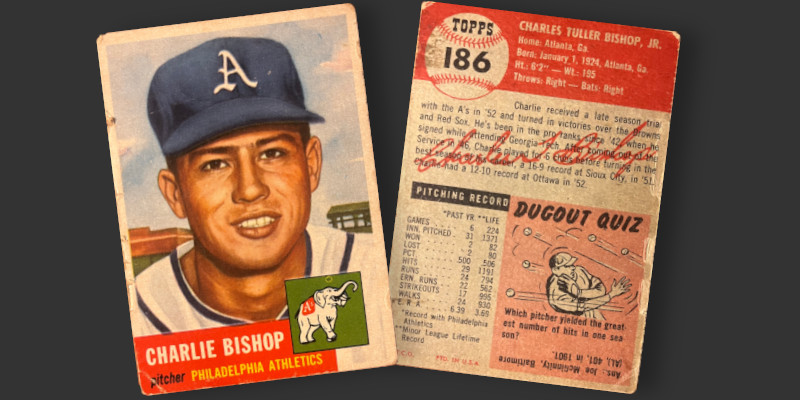

Making my way through the middle row, where the set collector guys with binder after binder of commons set up, my eyes caught sight of something familiar. Arranged in those oversized 8-page sheets was a binder full of 1953 Topps cards, and sitting on the bottom row was card #186. I knew that number without even flipping the card over to read the back. #186 was Charlie Bishop. Philadelphia Athletics starting pitcher Charlie Bishop. 1953 Rookie Charlie Bishop. The guy we hoped might pitch to us at the big family reunion that was planned for 1994. That Charlie Bishop.

He had come to our attention via a pair of unexpected baseball cards the previous summer. There was no chance of him actually attending the family reunion, as he was only tangentially related by marriage, lived many states away, and probably had never met anyone in my immediate household. That imagined reunion ballgame was never a realistic proposition. Still, my brother and I were fascinated by this connection to a guy who had drilled Mickey Mantle with an errant pitch in a big league ballgame.

I shrewdly asked the dealer with the binder how much he wanted for the Charlie Bishop card taking up too much space in the bottom row, and quickly volunteered that we were relatives before he could even quote me a price. The card was ten bucks. I had ten bucks. I told him I would take it and excitedly shouted for my brother to drop whatever Robin Yount card he was holding and to come over to my table.

The dealer, who had been wolfing down a family size bag of potato chips, reached a finger behind the card and slid it out of the page and into a waiting top loader. I’m going to need to buy a screw down for this, I thought. It didn’t matter that this card would have been solidly classified as “good” condition if not for some paper loss near one of the borders. I had added an actual ’53 rookie card to go along with the Topps Archives example I had in a box at home.

Even better than having it in hand was seeing a second Bishop card in the same binder page. The dealer had doubled up his duplicates to save space in his pages. My brother quickly handed over his own Alexander Hamilton note to secure his own copy. The dealer, who had been frantically wiping his hands on the sides of his pants, gingerly reached in and plucked out the second Bishop card by one of its corners. Holding the card carefully by the edges, he put it into a waiting top loader and handed it across the table to my brother. Hey kid, want some chips?

I didn’t realize it until we were on the way home, but that hand cleaning effort had made our almost identical cards very easy to tell apart. Appearing boldly across the biographical text on the back of my copy was a large, thumb-sized grease spot from the dealer’s mid-show snack. My brother’s card bore a similar mark, though his was far less visible and relegated solely to an area near the card number.

While I no longer have my sour cream & onion infused baseball card, I do happen to have the reduced fat copy above that my brother picked up from the show. It arrived in the mail from my Mom a few years ago, along with a better condition one she had picked up during a brief attempt at collecting with us in the 1990s. It’s a good card of which to have duplicates, which is fortunate considering I have close to two dozen of them.

And why not? It’s a fascinating piece of cardboard.

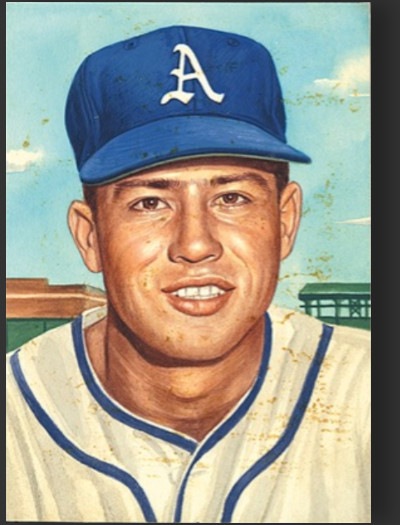

Like all ’53 Topps the image on the front comes from a watercolor painting based on a real black and white portrait. Topps contracted out production of these pieces to at least five artists, one of which was Jerry Dvorak who would go on to animate Popeye the Sailor Man, the Berenstain Bears, Strawberry Shortcake, and Casper the Friendly Ghost. Could Charlie have been painted by Dvorak?

Possibly, though it’s a longshot. At least five portrait artists were employed in the creation of the set, each presumably contributing a little more than 50 subjects to the checklist. Artist names are not provided anywhere in the image and Topps didn’t seem too forthcoming with this information. I am not aware of a comprehensive list of attributions, though that doesn’t mean we don’t have some clues as to who painted specific players.

George Vrechek wrote in some detail about the production methods employed to churn out so many watercolor paintings in a limited amount of time (working for Topps was not the artists’ day job). Rather than being sketched out by hand in advance, the images appear to have been sped along through the process by projecting reference photographs onto the medium and painting over it. Many of these photos were press shots with little in the way of backgrounds. As the project progressed, Topps directed Dvorak and the others to incorporate more ballfield infrastructure into the backdrop of their work.

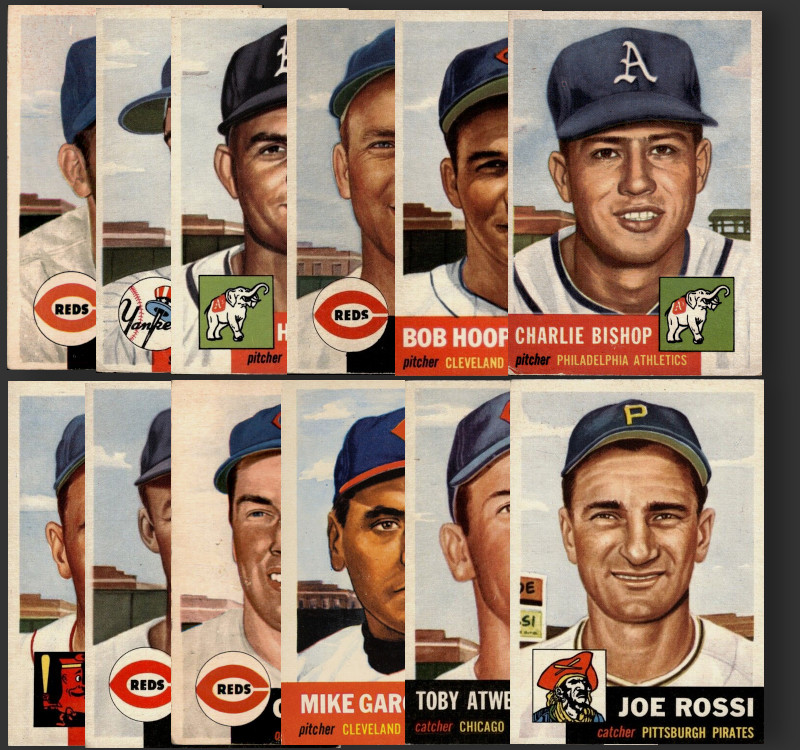

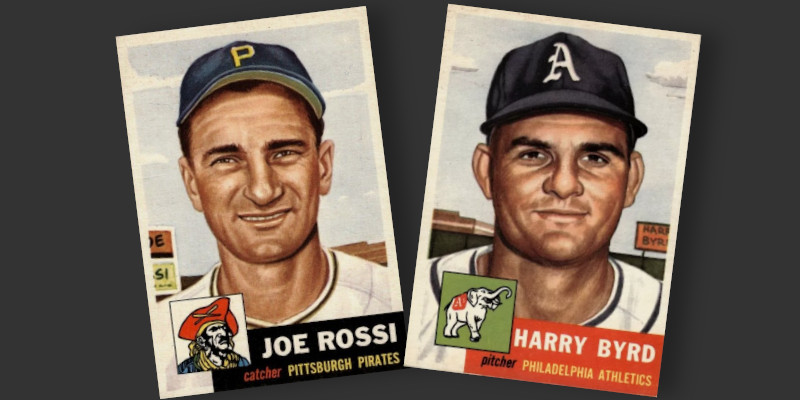

Here we get one of the clues as to which cards were painted by the same artist. Many make use of repeating background images shown at slightly different angles. Light towers, scoreboards, and even a small outbuilding behind a wooden fence are frequent backdrops. It is as if a handful of generic shots of empty stadiums and practice fields were projected onto the canvas as inspiration. The differing scaling and angles could be a conscious design call or, quite possibly, the result of setting up the projector at a slightly different position while setting up for a weekend’s worth of moonlighting as a baseball card artist.

My first thought when looking at the Charlie Bishop card was that it was set in Shibe Park. After all, that was the Athletics’ home park and it did contain double decker stands leading to a large outfield wall. However, the buildings beyond this infamous “spite fence” were narrow row houses that directly faced the ballpark. The only structure visible beyond the wall is a long, rectangular brick affair set 90 degrees off the course of what was supposed to be Philadelphia’s 20th street.

Looking through the rest of the set there are another dozen names clearly showing this same combination of stadium seating, outfield wall, and rectangular building. The same structure appears over the left shoulder of most of these cards, with a few additional cards placing it over the right. Odds are these cards were all prepared by the same artist as they were working independently of each other.

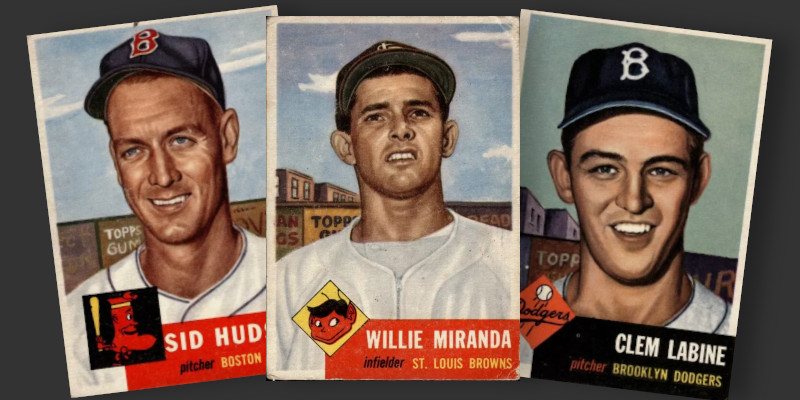

Dvorak was interviewed by Paul Green for Baseball Cards Magazine in 1984, and it was noted that after being told some of his work was too plain he planted a few easter eggs in a handful of the remaining paintings. Three players (Sid Hudson, Clem Labine, and Willie Miranda) had Topps’ name added to outfield advertisements. The latter two even share the same general backdrop.

How about player names being added to the same kind of advertising billboards? Yep, two more paintings showed up with names on the outfield wall. Even better, both came from the brush of whoever put that rectangular building behind the outfield wall. This isn’t conclusive evidence of the card being the work of Dvorak, but it does follow a pattern.

Perhaps the original painting would yield some sort of clue to its origin. The art, which measures only 3.5×5 inches, apparently went home with Topps’ Sy Berger following the production of the ’53 set. More than 100 paintings surfaced from his collection close to 20 years ago and were subsequently encapsulated by SGC. The Bishop image was part of this group and was last seen in a Robert Edwards Auction in 2010. No picture of the back was provided, though based on other pieces from the series likely consists only of a player name and tons of residual glue. I would love to add this piece to my collection if it ever resurfaces.

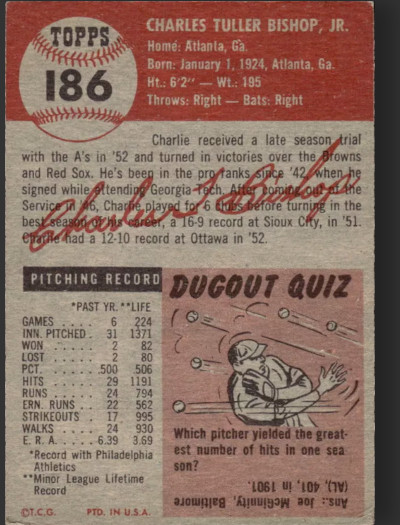

The back of the card offers a few more items to explore. For starters, the facsimile signature includes his middle initial, a touch that did not translate through time to his later autographs.

The biographical text mentions he attended Georgia Tech. This doesn’t quite match news accounts of his signing, which identified him alternately as either a semipro player or a product of Tech High School. It all probably looked the same from Topps’ offices in Brooklyn. The card itself does not mention that the franchise doing the signing was the St. Louis Cardinals, which tucked him away in their overstuffed farm system.

Each card in the ’53 release had a cartoon “Dugout Quiz” positioned in the lower right quadrant. This particular card asked readers to identify the pitcher who gave up the greatest number of hits in a single season. That turned out to be Joe McGinnity of the Baltimore Orioles, confusingly a forerunner of the New York Yankees and totally unrelated to the St. Louis Browns that would soon move and take over the defunct name.

There may have been a bit of foreshadowing involved in this little factoid. Bishop was seen as a fireballer, albeit with a penchant for wildness and giving up hits when his fastball missed its location. He appeared in 6 games during his cup of coffee with the 1952 A’s, surrendering roughly one hit per inning. He generated an above-average 5 strikeouts per 9 innings, but this was offset by a 1.73 WHIP. Still, he had shown enough promise to warrant a starting role with the club as they moved on from the days of Connie Mack managing from the dugout in a three piece suit.

He earned victories in his first two MLB starts, striking out 12 opposing batters while nearly recording a pair of complete games. Control issues cost him the next two decisions and he ended the year on a somewhat rocky note. After playing winter ball and almost authoring a no-hitter with Caracas of the Caribbean League, he began the ’53 season as the team’s 4th starter. His first outing saw him collect 2 RBIs at the plate and shutting out the Boston Red Sox. The rest of the season did not go as well as he finished the year with a 3-14 record and 5.66 ERA. Clearly there was more work to do.