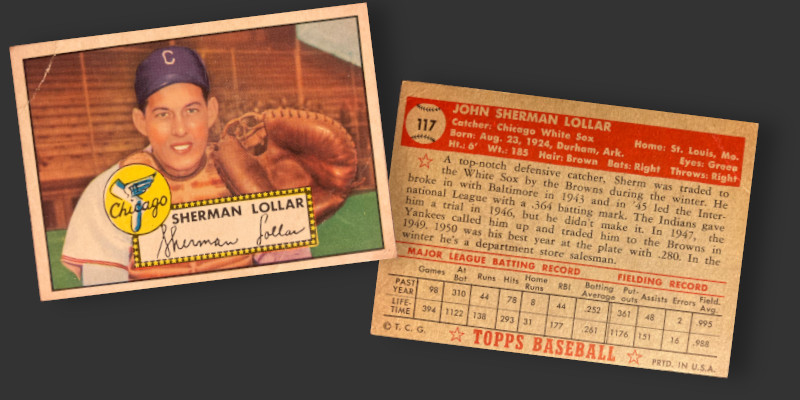

There is a distinct look to images appearing on 1952 Topps baseball cards, much like there is to motion pictures from the silent film era. A big part of this is ’52 Topps motif is the process by which color was added to the black & white images used to make the cards. A third party studio was contracted by Topps to apply Kodak’s Flexichrome coloring process, an arrangement that largely remained in place over a ten year period. This generally produced excellent results, as images were only augmented by the process’ pigments rather than actually painted over.

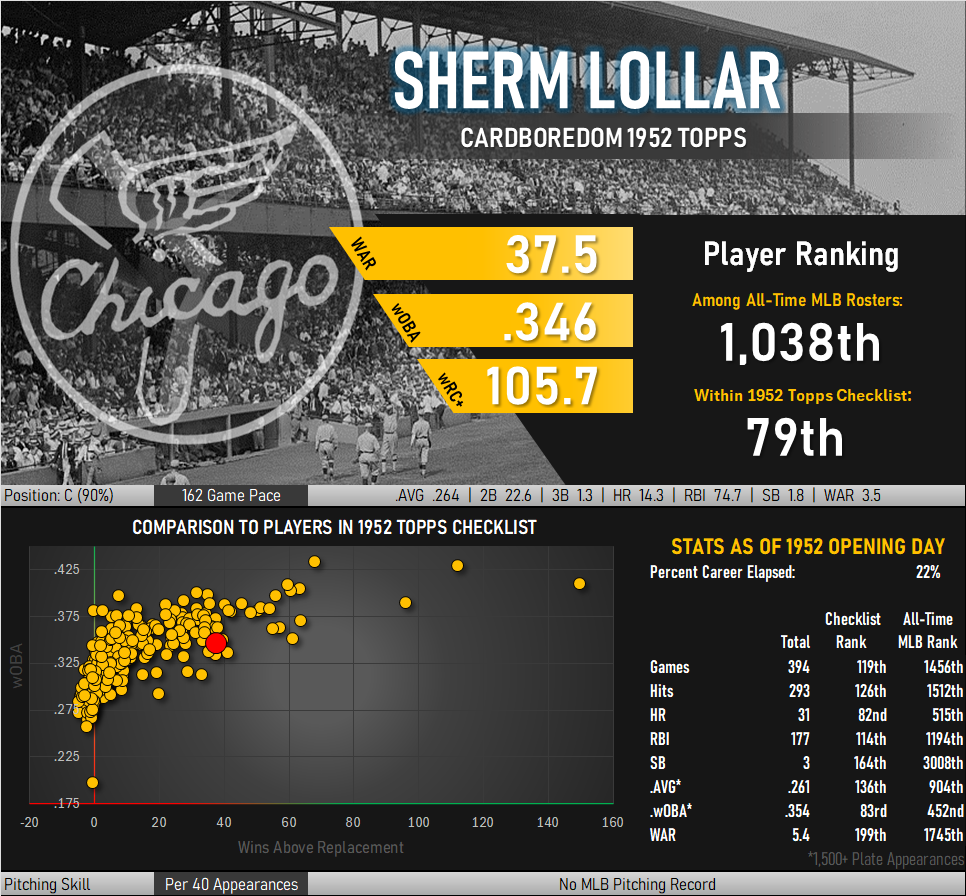

Some cards, however, emerged from the studio looking more like something that crawled out of the silent film era than the new color television broadcasts from CBS that had begun in 1951. Images like the one appearing on the above Sherm Lollar card did not look out of place 75 years ago but they certainly do today. What had so recently been a state of the art coloring process was turned into something antiquated by the arrival of new technology. Lollar looks almost as if he is in stage makeup, preparing to play the part of a catcher in a theatrical production.

Stage makeup provides example of this process in action. Theaters of the late nineteenth century were not the best lit places. Heavy makeup was applied to actors in an effort to render their faces more visible and to exaggerate expressions so that all parts of an oil-lit house could follow the action. Much of the acting world brought stage traditions with them, makeup included, as they transitioned from live performances to film.

Early film registered light and dark but had difficulty capturing certain colors. Although the output was always black and white, anything even partially blue in these orthochromatic films was rendered white and many reds and greens turned black. Heavy makeup remained standard for the industry while color palettes shifted in favor of hues that would generate the most visible outcome on the silver screen. The best known names of silent film would look out of place without heavy makeup. Take a look at Buster Keaton in The General or Charlie Chaplin in The Gold Rush. Both appear to have substantial eyeliner budgets at their disposal.

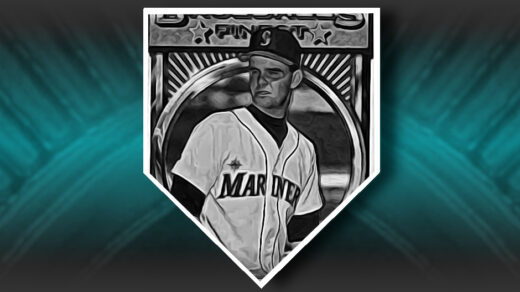

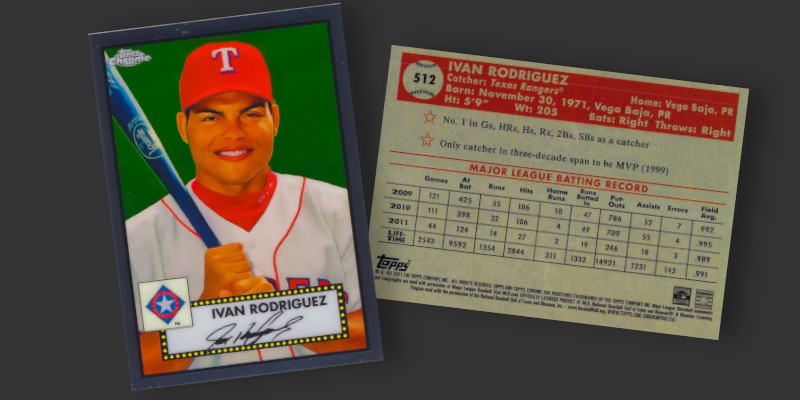

Lollar’s 1952 baseball card has drawn its share of comments in the past for its resemblance to the grotesques from silent comedies. Much of this has centered around the way the Chicago backstop almost appears to be wearing lip gloss. Topps, either through ineptitude or a genius level allusion, harkened back to this very card when the card manufacturer revisited the ’52 design for its Chrome Platinum Anniversary release in 2021. Lollar was the era’s archetype of a defensive minded catcher, though he could certainly hold his own with a bat. Ivan Rodriguez, another long serving defensive catcher, filled a similar role in the 2021 checklist. Topps applied the Photoshop equivalent of Flexichrome to his card and somehow ended up with this:

Ivana Rodgriguez, anyone?

Giving the Lollar color artist a little bit of a break, it is worth noting that the original photo needed substantial work prior to adding color in the first place. Lollar was to be depicted with the Chicago White Sox in the upcoming Topps release but had only been previously photographed in uniform with the St. Louis Browns and New York Yankees. Despite the letter “C” appearing on his ballcap, that is a St. Louise jersey hiding behind his chest protector. That “C” isn’t really there either, nor is the bill on on the hat itself. Lollar had been captured on film in the midst of a catching session and was still wearing all his equipment (check out that knuckleball-catching mitt!). Removing his mask for the photographer, Lollar had left his cap turned backwards. No self-respecting Chicago Southsider would have wanted to see their new player depicted as one of the enemy. To prevent any confusion as to where his professional allegiances lay, a Topps artist had to add a brim to the cap in order to make it conceivable that a Chicago logo would be visible. All that work on his cap may have resulted in his face needing extra work to offset the way in which a fake hat brim would have stood out.

One Hit Wonder

Lollar rightfully is seen as one of the better catchers of the 1950s and attending his fair share of All-Star games despite the presence of Yogi Berra in the American League. By 1959 fans had no trouble cheering for him as Chicago’s cleanup hitter, a role he found himself in on April 22 against the Kansas City Athletics. He hit a double in his first at-bat, scored from second on a Jim Rivera hit, and was intentionally walked in the fifth. A groundout from Lollar closed out the Chicago side of following inning of what to that point had been an 8-6 ballgame. That’s when things went crazy.

The White Sox returned to the plate in the 7th and promptly took advantage of a fielding error to get Ray Boone on first base. Al Smith attempted to bunt Boone over to second and ended up on base himself with the A’s committing a second consecutive error. Johnny Callison followed that with a single to right, scoring both Boone and Smith with the help of yet another error. Four straight walks (and a pitching change) later, the bases were loaded and the White Sox had added another 5 runs to their lead. The A’s finally got their first out against the next batter with a force play at home. Sherman Lollar came to the plate and promptly drew a walk and pushed the Sox scoring to 6 runs in the inning. Guess what happened next? With the bases loaded the A’s promptly walked the next two batters, hit the third with a pitch, and walked three of the next four after that. Eventually the A’s got out of the inning, but not before 11 runs had scored on just one hit.