Collecting the 1993 Refractor set took years of effort. This wasn’t just a period in which I would pick up a card if I happened to come across it. It was a time when I was actively searching for missing names, checking alerts for new listings and following up with collectors who might know someone who has a specific card. Some of those interactions were less than pleasant and forced having to repeat the process for a few names in the checklist.

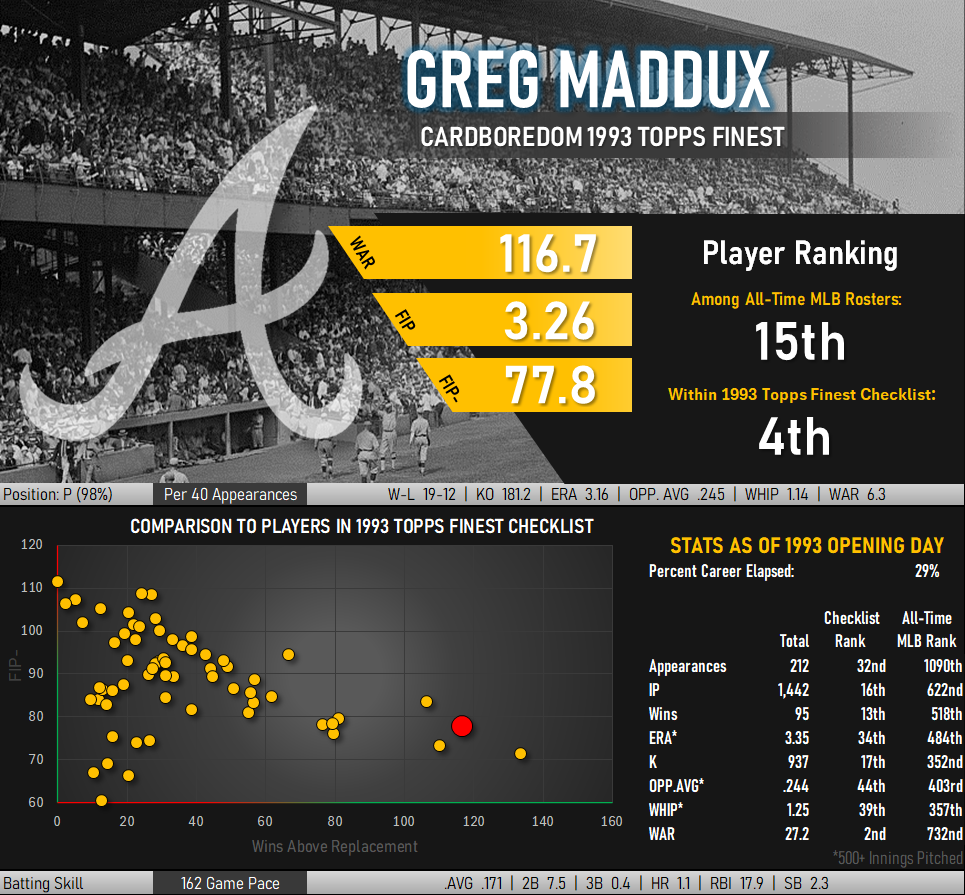

A few years ago I wrote about my experience of getting PSA and eBay involved with a mislabeled Greg Maddux card. I had purchased a slabbed Maddux refractor only to discover someone had misidentified a base card. After that disappointing incident I moved on to other cards, eventually making Maddux one of the final three needs of my set building project. I eventually found a suitable card of the four time Cy Young Award winner, adding it straight from a collection that deserves a special mention.

At one point during the early ’90s refractor mania, a collector wrote to one of the price guide magazines questioning the complete set pricing listed. Using the ’93 Refractors as an example, the writer wondered how accurate the pricing could be, given that very few complete sets were likely changing hands—especially for something so new and difficult to find. The magazine’s editorial staff responded by explaining their methodology: they analyzed historical patterns of how complete set transactions compared to the cumulative value of individual cards, then applied these models to the reported transaction prices of individual refractors. The editors concluded by noting they weren’t aware of any complete sets actually changing hands, much less ever being completed.

Enter a collector named Doug, the guy from whom I purchased the Maddux card shown above. After receiving the card in the mail, I reached out to him to ask if he had any stories about how he came to own it. Doug, it turns out, had quite the tale to relate. He started collecting cards with his son in 1993 and soon cannonballed right into the deep end. Within a year he had set a goal of building the ’93 Refractor set. Two years later he finished it, becoming one of the earliest to ever accomplish the feat. Not only had he located each of the 199 names in the checklist without thriving online hobby outlets, his set was fully graded by PSA. He tracked this down in a fully analog collecting world, one in which slabbing modern cards was almost unheard of. After completing the set he was on the way to his next challenge, selling his full set at the 1996 National Sports Collectors Convention in Anaheim.

Almost 30 years later Doug is back for another round of collecting and has once again assembled another amazing group of cards. Congrats, Doug. I’m glad my collection has this small connection to yours.

Umpires

Can we talk about umpires for a moment?

If you sit at enough ballgames you will eventually hear a recurring string of blind umpire jokes. Looking back to 1908, Bob Emslie—to that point the longest tenured umpire in baseball history, was famously called “Blind Bob” by John McGraw after his role in the infamous “Merkle’s Boner” play that resulted in an apparent 2-1 Giants win being turned into a 1-1 tie with the Cubs. This came just two weeks after an almost identical incident reversed an apparent Pirates victory against the same squad. [Fun fact: To stop McGraw’s whining about his eyes, “Blind Bob” subsequently brought a rifle to the next Giants practice and accurately shot a dime off the pitcher’s mound.]

It almost seems traditional to hear the notes of “Three Blind Mice” eminating from an organ after a close call at the ballpark. As far as I can tell, Nancy Faust was the first to apply this joke to keyboard and foot pedals soon after joining Chicago White Sox as the team organist in the 1970s. Wilbur Snapp, the organist for a minor league affiliate of the Phillies in Clearwater, was famously ejected by an umpire for playing these same bars after a contested call.

What’s interesting about all of this is the fact that I have never heard a heckler in the stands or a dugout accuse the ump of being deaf. While visual cues are undoubtedly important in getting calls right, auditory signals are often just as important.

Judging when a base runner beats a throw is a potentially game-altering decision that happens at incredibly high speed. Visual confirmation is typically not employed as the umpire’s eyes are fixated on the bag to monitor the foot placement of the runner and the player defending the bag. Confirmation of the incoming throw’s arrival time comes from listening for the telltale “pop” in the receiving glove. Some of the game’s best defensive infielders developed the uncanny ability to simulate this sound a split second before the arrival of the ball, nudging foot-focused officials into swinging close plays in favor of the defense.

Keith Hernandez, known for standout defensive work at first base, credits a whole range of similar actions with helping his teams. His footwork, which included a well-timed and slightly early step away from the bag, with getting the New York Mets past the Houston Astros and into the 1986 World Series. In Game 5 of the NLCS he managed to get a double play call against Craig Reynolds, later telling an interviewer “he clearly beat it, but I cheated and we got the call.”

The goal for fans is to have official scoring match the activity that takes place on the field, but far too often it does not and yet spectators seem to tolerate, if not cheer, poor calls. This is something that keeps me from taking the sport seriously or caring too deeply about things like the Steroid Era or the waste management practices of the Astros (or Yankees, Red Sox, White Sox, etc). The sport seems happy to let these practices take place and only does something about it long after problems become endemic.

Getting the call right is a core public service for all involved, yet widespread cheating (even if small scale) gets cheered. Imagine how your local government would work if the general population accepted widespread low level bribery as “just a part of the game.”

When You Frame It That Way…

So why the tangent about wrong calls? It all comes down to framing. While mildly dishonest infielders garner subtle nods of appreciation from the sport, catchers have seen a wave of outright admiration for chicanery.

Long a staple of catching duties, “pitch framing” has seen much higher visibility over the past two decades. Essentially, this entails a catcher positioning himself and moving his glove in such a way to draw more favorable ball/strike calls from the umpire covering home plate. This is perfectly reasonable when it nudges the umpire to call a borderline strike a strike or avoids the umpire blowing a call by mistaking a perfectly good corner pitch into an unwanted walk. However, like the “better” infielders mentioned earlier, a good number of catchers also employ subtle tricks to transform obvious balls into strikes. With perhaps 150 pitches coming their way every game, stealing a few bad calls from the umpire crew adds up over the course of a season.

Within a few years the Cooperstown discussion will come up for a pair of catchers who excelled at tricking umpires. Both were exceptionally good players, but fit more into my definition of “Hall of Pretty Good” rather than Hall of Fame. Knowing this, fans making arguments for their induction have leaned fairly heavily on their above average framing skills. The argument of “Yeah, he was pretty good but you should have seen the way umpires blew calls around him” doesn’t hold much sway for me. Relying on mistaken calls to edge over 75% in BBWA voting seems…like a bad call.

That said, pitch framing has traditionally been seen as the domain of they guy impersonating a hockey goalie behind the plate. What if the pitcher were able to channel this malevolent superpower of mind control over umps? Greg Maddux did.

Maddux wasn’t overpowering. A quick and inconclusive search revealed no pitch leaving his hand faster than 93mph, and even that figure was a rare sight through the lens of a radar gun. This is slower than his top line peers of the era, but speed isn’t everything. His breaking pitches arrived with huge differentials in velocity compared to his fastball, maintaining the effectiveness of changing up pitches. His pitches also possessed later breaking movement than most, effectively reducing batters’ reaction times in the same way much faster speeds would do.

Furthermore, Maddux possessed extraordinary control over his pitches. He could quite simply (and consistently) place a ball anywhere he wanted. From 1988 onward, he famously faced 19,576 batters and drew a 3-0 count just 644 times, a number that shrinks dramatically when you factor in the couple hundred intentional walks included in this figure.

That late movement and precision in placing his pitches had an effect on umpires. Maddux was able to consistently get balls turned into strikes at a rate far beyond other pitchers. More than 70% of his pitches were called as strikes. Late movement made balls appear as strikes with umpires paying more attention to the early trajectory of pitches rather than the final moments when the ball crossed the plate. Maddux’s reputation for pinpoint control swayed even more umpires to give him the benefit of the doubt, admiring close calls as “painting the corners of the plate” rather than being a wayward pitch. He consistently hit the same midair targets again and again, making everything seem intentional and controlled. He directly challenged batters, daring them to hit strikes rather than throwing junk around them. He didn’t argue calls with umpires, seemingly agreeing with however they called his pitches. All of this combined with umpires generally leaning in his favor to effectively give Maddux a larger strike zone than the rest of the league.

Enough Ranting

That’s enough being an old man complaining about bad calls changing the outcome of ballgames. Yes, Greg Maddux benefitted from these calls consistently falling in his favor, but that isn’t the reason why I have him ranked as the third best pitcher of all time. He had the underlying skill to be good regardless of officiating decisions.

Maddux was durable, pitching more complete games in the 1990s (73) than any other pitcher and pretty much doubling the tally of anyone since that time. His ERA in the high offense Steroid Era (2.54) was better than Dwight Gooden’s 1980s stat line and would have placed him third among hurlers in the 1960s Decade of the Pitcher. He was able to rack up impressive numbers regardless of run support, leading the National League in wins in 1992 despite playing for the last place Chicago Cubs.

If anyone could have shrugged off the move to baseball’s introduction of ABS next season, it would have been Greg Maddux.

Perhaps there wasn’t even a need to worry about those called strikes and balls. Maddux was so renowned for his efficiency that a part of the game was named after him. A pitcher is now said to have thrown a “Maddux” after recording a complete game shutout on a double digit number of pitches. Maddux himself threw 13 of these in his career, 3 more than all MLB pitchers combined since 2010.

Bottom of the Ninth…

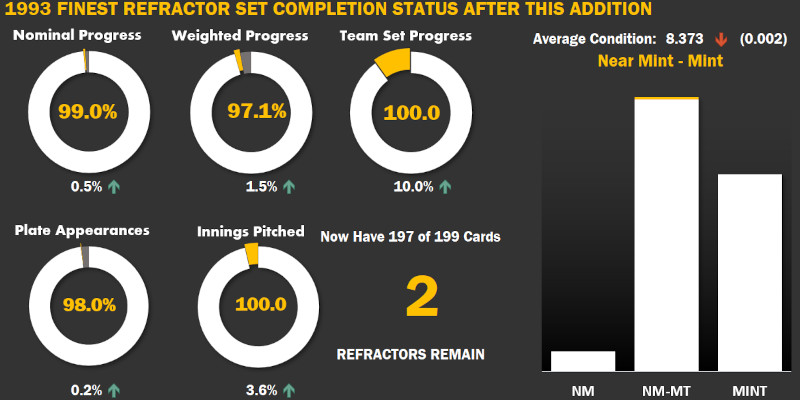

It took years to get this point in my quest to complete the 1993 Finest Refractor set. I was down to the final three needs when Doug helpfully supplied this card. With three names left to punch out, it seems like the bottom of the ninth has finally arrived for this endeavor. With Maddux finally locked away, it’s one down and two names to go.