The 1936 high school graduation of Bob Feller was broadcast live over the radio so baseball fans could follow the progress of the pitcher that was soon to arrive in Cleveland. It seemed that the entire league was waiting for the teenager to make his debut.

Two years earlier, while Feller was still in school and on the shore of a different Great Lake, another student was grappling with his own path to the majors. Phil Cavarretta’s family had been hit hard by the continued effects of the Great Depression. In his senior year he informed his school that the need to support his family through immediate employment would make his graduation unlikely. Cavarretta’s baseball coach reached out to the Chicago Cubs and arranged a tryout, at which the 17 year-old was nearly laughed out the park when he made his entrance. The laughter quickly stopped when he held his own in a major league batting practice.

Cavaretta was immediately signed by Chicago and proceeded to tear his way through the minors. He was brought up for a cup of coffee at the end of the season and managed to log a .381 batting average in 7 games. When the 1935 season opened he was the new starting first baseman. On May 9, just shy of one year from his first professional game, Cavarretta and the Cubs traveled to Boston to take on the Braves. Twice he found himself face to face with Babe Ruth, who drew a pair of walks. Ruth, it should be mentioned, famously hit his “called shot” against the Cubs at Wrigley Field in the 1932. From his time in grade school Cavarretta would regularly help clean those very stands in exchange for free admission. The distance the new first baseman had come in less than a year was remarkable.

Brushes with baseball greats continued. The Cubs of this era were perrenial contenders and earned their fair share of high end matchups. Ruth retired in 1935 and Cavarretta’s Cubs went to the World Series that season. They returned again to face the Yankees in the 1938 Series, with Lou Gehrig taking time to personally tell Cavarretta that he liked the enthusiasm with which he played. He faced off multiple seasons against Carl Hubbell and Dizzy Dean, with the latter then becoming a teammate when the Cardinals pitcher switched teams.

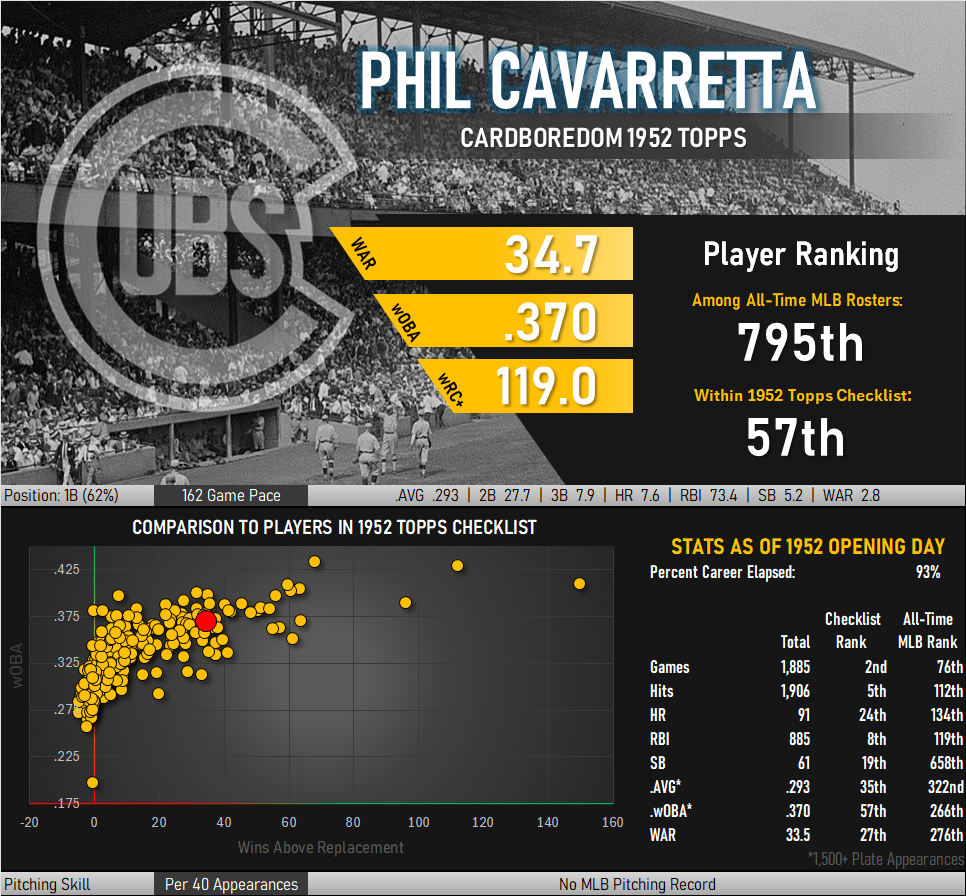

Nobody could accuse Cavarretta of just being along for the ride. He was a fine ballplayer and would go on to crack the Top 10 list of most hits in the 1940s. He was the National League MVP in 1945, capping off the season with a .355 average and the batting crown. While he wasn’t much of a home run threat with just 95 HRs over 22 seasons of play, he still managed to generate a weighted on base average of .370 (equal to Sammy Sosa and Yogi Berra).

That kind of play allowed Cavarretta to amass a lengthy stay in the majors. He played for 22 seasons. 20 of those years were as a popular member of the Chicago Cubs and to this day rank him 2nd in team history for most seasons with the club. If any of this year’s newcomers to the team eclipse his mark, it will take place a full century after he garnered the ’45 MVP award.

Cavaretta’s time with the Cubs ended at the conclusion of the 1953 season. He took up residence for two additional years with their American League counterpart, the Chicago White Sox. This is a a bit of a disappointment, as beginning in 1954 the Cubs played regularly against the Milwaukee Braves. Cracking the starting lineup for the team was a young shortstop turned outfielder by the name of Hank Aaron. Phil Cavarretta began his career trying to hold Babe Ruth on first base. He ended it as a contemporary of the man who would one day supplant Ruth’s home run crown. He is the only player who played alongside both men.

A Potent Cardboard Legacy

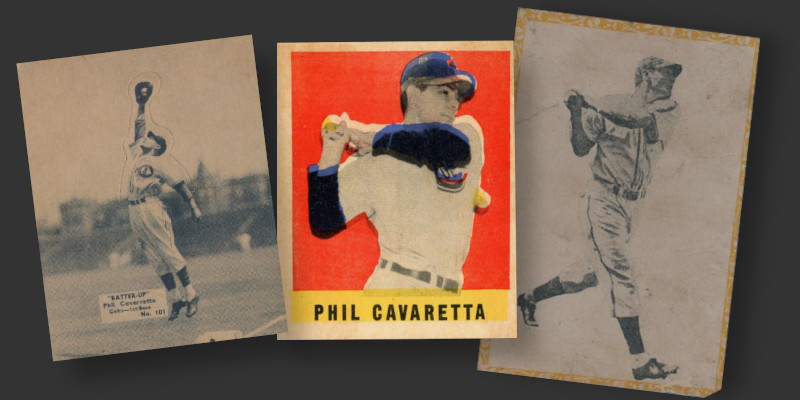

Inhabiting the period between Ruth and Aaron, Cavarretta arrived in an often overlooked part of baseball card history. He has some fantastic cards, with many found in slightly obscure but highly collectible issues.

Cavarretta was overlooked by Goudey in the gum producer’s 1935 issue, but managed to get included in the much harder to find 1936 edition. Goudey put out two baseball sets that year, both featuring black & white images with player names prominently written in cursive. The sets are differentiated by their backs and the width of the penmanship used in player names. Cavarretta appears in the larger “wide pen” release and exhibits one of the better action shots available.

This surprisingly is not his rookie card. Cavarretta made his cardboard debut in the Batter Up cards produced by National Chicle in 1934-1936. He appears in the harder to find high number series, a development that makes sense considering the first half of the set was already on store shelves before he ever set foot on a major league diamond.

Like a lot of players, he disappeared from card issues throughout much of the 1940s. He resurfaced in both the 1949 sets produced by Bowman and Leaf. The Leaf issue is of particular interest as he is one of the famously difficult short prints so often sought by collectors.

Baseball cards essentially vanished from US shelves during World War II and returned slowly, not regaining widespread issuance until the very end of the decade. Other markets were much quicker to recover. Cuban candy maker Montiel produced a 180-card series of multisport caramel cards in 1946. Interest in these cards has risen in recent years and reigning MVP Cavarretta is right there in the checklist with the likes of Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Martin Dhigo, and even what could be considered a rookie card of Stan Musial.

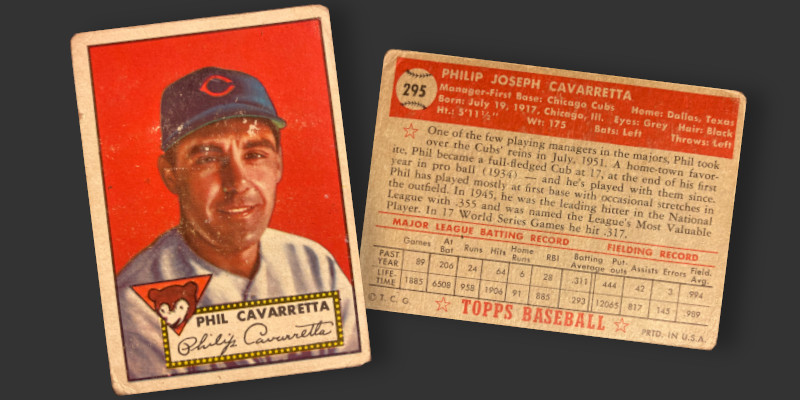

Player Manager

Phil’s impressive cardboard doesn’t stop with just these issues. He appears in the somewhat challenging fifth series of 1952 Topps. The position listed on the back is that of “Manager-First Base,” reflecting his 1951 promotion to the ranks of player-managers. Only 35 years old at the start of the season (the card has the wrong birthdate), he is one of a half dozen MLB managers active aged 36 or younger in the 1952 season, most of which were also active members of the playing roster. The biographical text on the back begins by describing him as “one of the few playing managers in the majors.” Other player/managers appearing in the ’52 Topps checklist (i.e. Eddie Stanky/Fred Hutchinson) omit their position as managers, reporting only the positions they play on the field. A third, Tommy Holmes, had been dropped from his role with the Braves prior to his card’s production. Without a team at the time of the Topps release, his card describes his position only as an “ex-manager.”