The anchor of a pitching rotation in the DH-enamored American League is rarely known for batting prowess. And yet, a series of unplanned at-bats prepared the way for hurler Charles Nagy to work his way towards a perfect 1.000 batting average in 2001.

Charles Nagy was a workhorse pitcher for the Cleveland Indians of the 1990s. He threw more than 250 innings in 1992 alongside multiple shutouts and double digit win totals for a team that finished below .500 and 20 games out of contention. His services on the mound were very much recognized by the Cleveland fans who voted him to the American League All-Star Team.

Nagy came into the ’92 All Star Game in a seventh inning relief role. With the American League up by 9 runs and having already chewed through the entire roster of position players, the rest of the game was spent juggling relief pitchers through a series of position switches. Nagy was technically replacing second baseman Carlos Baerga in the AL lineup and was called upon to bat in the eigth inning in what would be his first ever MLB trip to the plate.

Nagy found himself in the unfamiliar position of facing former teammate Doug Jones while wearing an even more unfamiliar batting helmet borrowed from Texas Ranger Ruben Sierra. Nagy beat out an infield single and promptly apologized to Will Clark and the first base umpire for doing so. Sierra’s helmet was traded out for that of Ivan Rodriguez as the unexpected hit brought Sierra to the on deck circle.

Clearing taking swings in the batter’s box was not a common practice for a pitcher who had yet to start kindergarten when the designated hitter rule took effect. Nagy started taking the occasional hack at the ball when interleague play in 1997, but didn’t limit these plate appearances just to facing National League opponents.

During the July 22, 1999 game against the Toronto Blue Jays, Nagy faced off against David Wells and lost 4-3. Cleveland manager Mike Hargrove had penciled in Nagy as the starting pitcher and a couple guys named Ramirez to play right field and DH. Manny Ramirez jogged out to right field to start the game and grounded out to short in the bottom half of the inning. Unfortunately for the Indians, Manny had been written into the lineup card as the DH with seventh-hitting Alex Ramirez slotted into right field.

Toronto’s manager brought the discrepancy to the attention of the umpire crew. After much head scratching and conferring, the umpires collectively ruled that Alex Ramirez had been the official starting right fielder with the appearance of DH Manny Ramirez in that role creating a substitution. As a player who had been substituted for, Alex would not be eligible to play for the rest of the game. Additionally, the synthetic abandonment of the DH slot meant Cleveland had to bat its pitcher in that part of the lineup. Nagy went 0 for 2 at the plate and pitched six full innings, making him one of eight pitchers in MLB history to take up the role of DH in which they also took the mound.

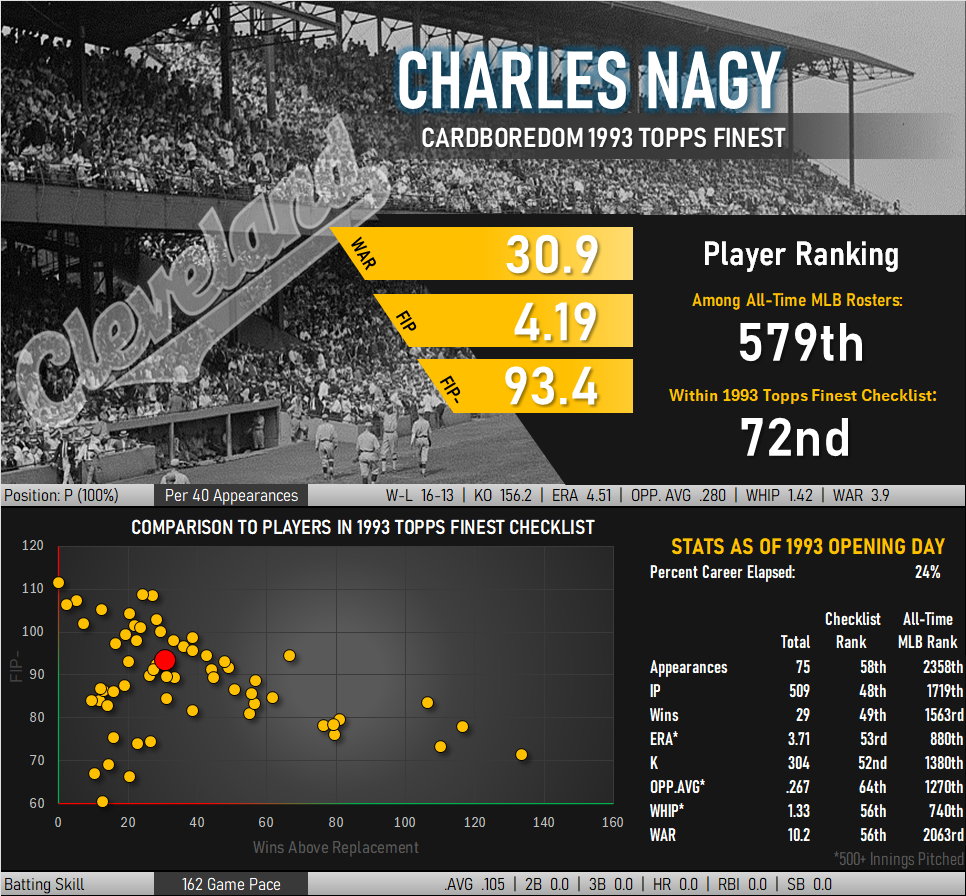

Despite getting his first MLB hit while apparently swinging with his eyes closed, Nagy’s career batting average of .105 and zero lifetime extra base hits approximated what one would expect from a 1990s American League pitcher. However, these plate appearances did provide future Immaculate Grid players with a secret weapon: He batted a perfect 1.000 with a 1 for 1 stat line in 2001.

An Alternative Definition of “No-Hitter”

The closest Nagy ever came to authoring a no hitter was a one-hit affair against Baltimore in 1992. Games like that make general managers smile and stock coaching staffs with retired pitchers. Nearly a decade after conclusion of his Cleveland career (and a 5 game stopover with San Diego), Nagy was hired as a pitching coach with the Arizona Diamondbacks where he served for three seasons.

Nagy was one of the first hires of newly installed GM Kevin Towers, who had encountered him during that brief period with the Padres. Three years later Towers dismissed Nagy, citing the coach’s refusal to order pitchers to intentionally hit opposing batters. Nagy, who had hit 51 of the 8,454 opponents he faced, didn’t see this helping his team in any way. How is giving the other team a free baserunner going to help?

I get the idea of wanting to retaliate against a headhunting team, but why hurt your own chance of winning the game in the process? Why not fire a fastball into the dugout and hit the guy ordering a hit by pitch? Pitchers are hired for their accuracy, so finding the right target shouldn’t be that difficult. Finding himself on the receiving end of numerous inside pitches, Brooklyn’s Carl Furillo famously got into multiple fistfights with Giants manager Leo Durocher.

Speaking on the subject Nagy’s release, Towers told reporters that hitting opposing batters was a necessary part of the game that generated protection for the team’s lineup. There was no response when it was pointed out that Diamondbacks pitchers were already drilling opposing batters 50% more often than other teams. Towers, a lifetime minor league pitcher who topped out with 27 games at the AAA-level, didn’t see the problem with this. He hit 27 batters across a much smaller sample size en route to a 29-40 record.

It seems those who can, do. Those who can’t make it a point to tell those who can how to do their job.