Several archetypal athletes that make up the game of baseball. Many are naturally talented individuals who slogged away with a decade or more of practice to get to the majors. There are multi-sport phenoms who select baseball from a menu of sports in which they could have had long, productive careers (Walt Dropo). There are players who walk onto a field with no prior experience, ask to try out, and then become Hall of Famers (Robin Roberts). There are the guys (Bob Feller) molded from birth by their parents to be the best of their generation. A few made it to the majors despite their parents trying everything to prevent them from playing the sport.

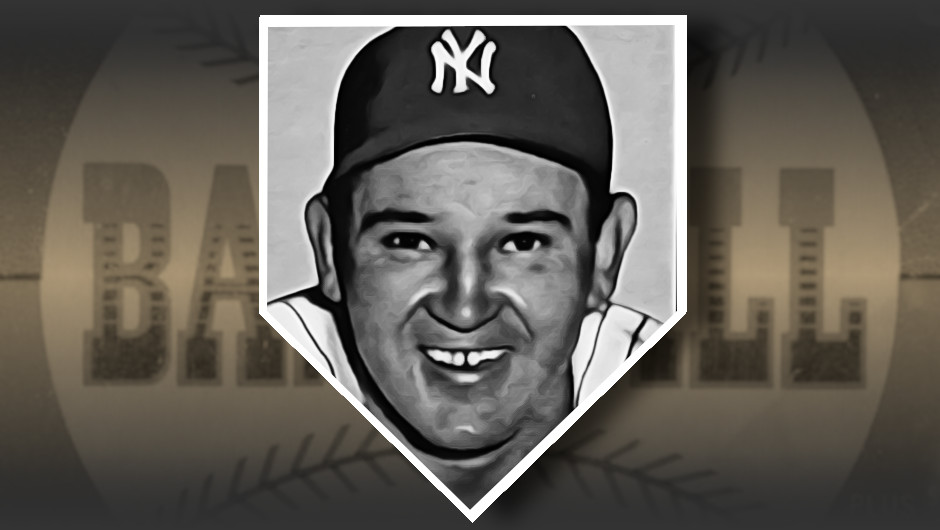

One of these players impeded by his parents was Allie Reynolds. His family was heavily involved in the Church of the Nazarene, one of the more austere sects of Christianity to grow out of the explosion of itinerant preachers and new denominations in 19th century America. The result was a total ban on playing sports on Sundays, negating Reynolds ability to join local teams as a kid.

He wouldn’t play organized ball until he was pulled away from his track & field training in college to fill in for a missing batting practice pitcher. That practice ended much the same as when Robin Roberts walked over from the football field in college and asked his school’s baseball team if he could try any open position. Both pitchers, with little to no organized pitching experience, proceeded to strike out established batters with ease.

A few years later he was one of the key members of the Cleveland Indians’ starting rotation. During the first half of his career he was essentially used as the team’s replacement for Bob Feller who had enlisted in the Navy in 1941. When Feller returned Reynolds was traded to the New York Yankees which he promptly led to a record five consecutive championships.

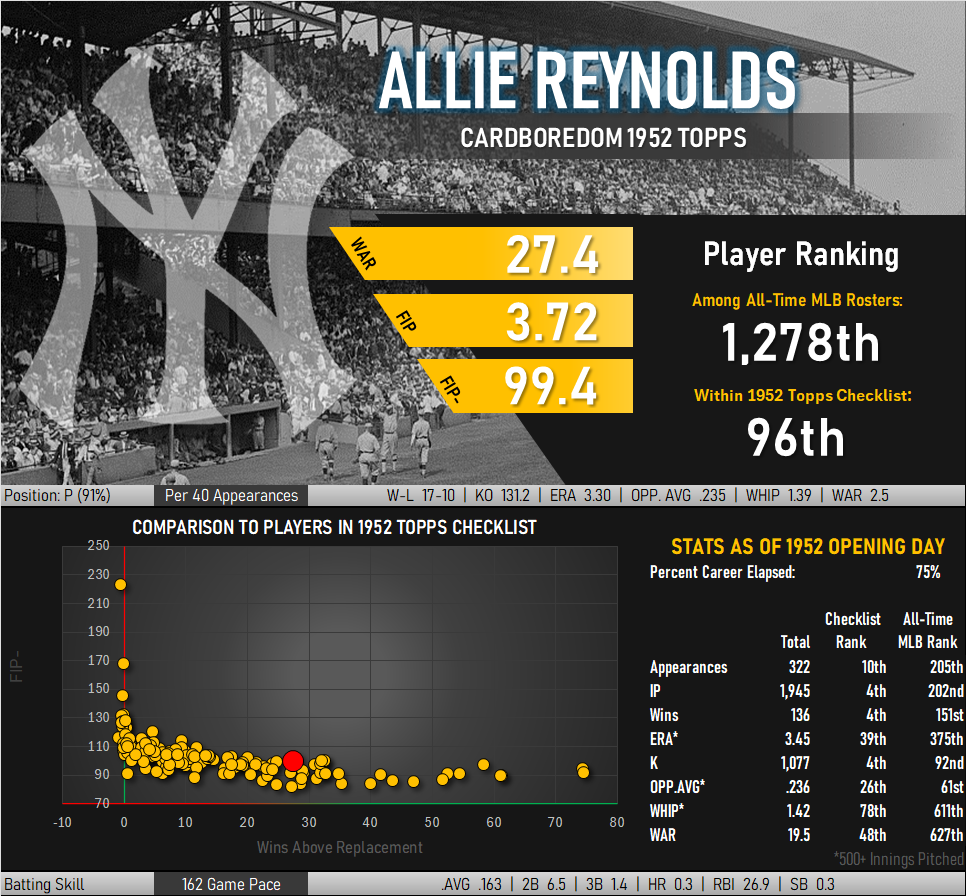

Reynolds’ career was effective but ultimately truncated compared to some of the better remembered names of the era. He has seen occasional interest from Hall of Fame voting committees but is (correctly) relegated to a solid position in the Hall of Pretty Good. His advanced metrics are decent (good, but not great) while it his World Series win-loss record that keeps him coming back in front of voters.

My Best Worst Card?

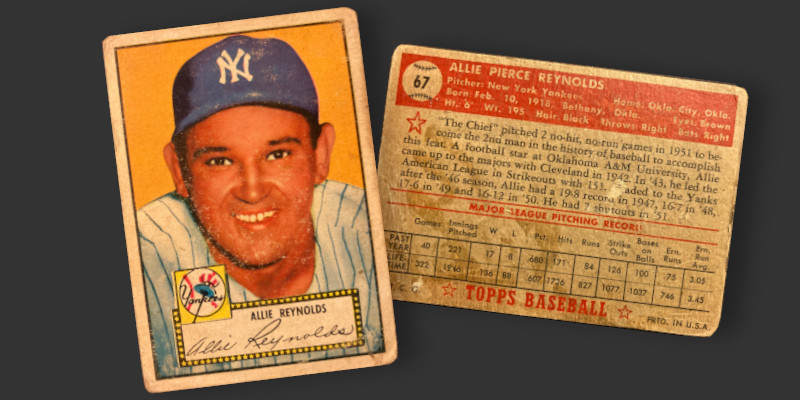

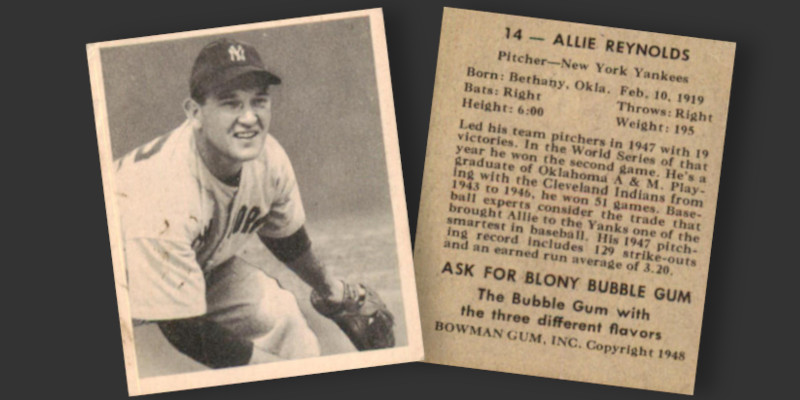

Shown below is the Allie Reynolds card I have added to my 1952 Topps set building project. There is some gunk and paper loss on the back, but check out that centering! I’ve been shuffling through so many cards from this set that I almost forgot what they look like when the guy operating the cutting machine puts on his glasses. This card is in very rough shape but it just might be the best centered example of the set in my collection.

I’m a big fan of many of the solid-background pictures in the set. Despite the surface wear on the face of the card, the color still pops. Like many first series cards it is available in both red and black-backed varieties with the red versions often exhibiting better color.

From the back of the card one can see that Reynolds threw two no-hitters in the season prior to this card’s production. Referred to as “The Chief” in the writeup, he was by this point resigned to the fact that newspapers would never stop using that nickname to reflect his 3/16th Muscogee ancestry.